The Suffrage Movement at Vassar

Early in 1913, when President James Monroe Taylor of Vassar College gave notice to the Board of Trustees that he intended to retire within the year, rumor held that “friction, suffrage, and socialism,” as he put it in a letter to Smith President Marion LeRoy Burton, had influenced his decision. This he denied, though the evidence suggests that as an unyielding conservative his patience had been tried and his energy sapped by student radicals, by faculty bent on self-government and by alumnae wanting a larger role in the affairs of the college. In 1918, after only three years in office, Taylor’s successor Henry Noble MacCracken was asked to resign by a powerful group of conservative trustees. In an angry private memo, MacCracken wrote that his resignation had been forced because “I stand for progressive and democratic management in college administration; for freedom, self-government and trust in the student body; for the advance of woman through the suffrage and through every other means by which man may welcome her as friend and comrade in the business of life. They [the trustees] have stood and now stand against all these things. They complain that I cannot ‘manage’ my faculty, that I spoke for suffrage last year, that I am not safe.”

In this paper we describe the crisis at Vassar occasioned by the woman suffrage movement, which in public debate was often linked to broad questions of social reform and which at Vassar became entangled with questions of academic freedom and self-government. In the struggle at Vassar opposing ideas were forced out into the open concerning the proper sphere of women, the nature and function of higher education for women, and the rights and duties of individuals in relation to institutional authority. At Vassar, both the conservative Taylor and the progressive MacCracken were troubled by radicalism as each fought–though with different allies–to maintain order in the college while imposing a vision of institutional values and goals. In the outcome, Taylor’s traditionalism slowly gave place to more democratic practice, though the process was resisted by the opponents of change and slowed by the habits of caution and mediation required of a college president of whatever stripe, whose duties include keeping institutional order and maintaining tradition.

President Taylor, the last in a line of Baptist ministers to head Vassar, held office between 1886 and 1914, during which time he did much to develop the academic strength of the college by, among other things, appointing capable faculty, many of them women. But he believed firmly that during their college years students should pursue their studies in disinterested tranquility, freed from demands for political or social commitment, and when, after the turn of the century, debate over issues of social reform increasingly intruded into the college preserve, Taylor laid down a rigid policy against public discussion of controversial issues on campus. He also spoke out against the ideology of reform, and in 1909 composed a speech which he then had printed and circulated, entitled “The ‘Conservatism’ of Vassar.” In it he said that “Vassar College recognizes all good service as worthy. It scouts the common opinion of the agitator that the best life is in the public eye. It does not love notoriety for the undergraduate, and declares it to be unhealthful, intellectually and socially… It affirms its belief in the home and in the old-fashioned view of marriage and children and the splendid service of society wrought through these quiet and unradical means.”

Though Taylor’s conservatism was supported by the Board of Trustees, composed largely of Protestant clergy and business-men, his view of the good life for Vassar women was undermined by certain of his own faculty. Among them, for instance, was the historian Lucy Maynard Salmon, who advocated faculty self-government and taught her students to go straight to primary sources, study the evidence and draw their own conclusions instead of depending on interpretation and received opinion. In the department of English were Laura Wylie and Gertrude Buck, who taught that individual experience of the world should be integrated into writing and showed that literature is not simply belletristic but contributes to the shaping of social and intellectual movements. In the recently formed Economics Department Herbert Mills taught courses with such titles as “Social Reorganization” and “Charitites and Corrections,” and sent his students out of Vassar into the social world All of these faculty members, and others as well, were advocates of woman suffrage and proponents of an ideal of social service rather than domestic virtue for educated women that ran counter to the views of President Taylor.

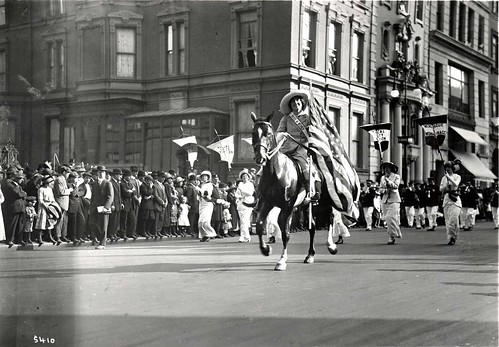

Faculty opposition to Taylor’s policy remained muted, however, until the campus was thrown in turmoil by a charismatic student radical named Inez Milholland. In June 1908, while the Vassar alumnae were back on campus for a reunion, Milholland, then a junior at Vassar but soon to enter the public arena as a star speaker for woman suffrage, invited Harriot Stanton Blatch ’78, Helen Hoy ’99, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Rose Schneiderman to speak on the suffrage issue. The meeting was conducted in the cemetery directly across the street from the College, a place chosen to draw conspicuous attention to the fact that it was not being held on campus. The “graveyard rally,” as it came to be called, was attended by about forty students and others and was reported in the New York newspapers, garnering exactly the sort of publicity President Taylor most deplored.

In March of the following year, Inez Milholland again made arrangements for a debate at Vassar about suffrage, this time by first taking a poll among the students of objections to women having the vote, then inviting faculty and students to answer those objections at a meeting in a college lecture hall. Evidently, a misunderstanding arose; Taylor gave permission for the meeting in the belief that no faculty members were to be among the speakers, and was angered to learn that they had been. In a stormy faculty meeting a few days later, he accused participating faculty of flouting his policy against official discussion of controversial issues on campus and was answered sharply by several who pointed out that he had opened himself to the charge of attempting to curtail freedom of speech. In a letter to Taylor subsequent to this meeting, Mary Whitney of the Astronomy Department put her finger on the central issue: “I am afraid that if we do not come to a clear understanding of the difference between propagandism and freedom of discussion… rumors of repression will get abroad… Suppose, in this unfortunate case, the instructors when asked had said, ‘The Policy of the college forbids my speaking.’ The result that has so disturbed you would have been avoided, but a far greater danger in my opinion would have been incurred.”

These events marked the beginning of significant student interest in suffrage activity, which grew slowly but steadily over the following years until Vassar acquired a reputation as a “hotbed of suffrage and socialism.” In April 1912, 478 students signed a petition for open discussion of woman suffrage on campus, and followed it with a mass meeting in the Assembly Hall. The New York Tribune observed on April 4, 1912, that “the question has never before been publicly discussed here, and the eager interest of all the college was shown by the great number that turned out.”

Among the faculty, two matters were coming to a head. In December 1912, thirteen faculty members drew up a resolution criticizing President Taylor and the Board of Trustees for their decision-making procedure. In it, they argued that faculty should be allowed to make decisions about matters relating to campus life. This protest was occasioned by the failure of Taylor and the Board to consult the faculty concerning a reorganization of a system of advising on campus. The names of faculty who had been active in the suffrage movement were prominent among the signatures on the resolution. Taylor considered that his methods were being “impeached” on all sides, and two months later, he gave notice to the board that he intended to resign as president within one year. He gave as his reason that after forty years of service, twenty-seven of them at Vassar, he was tired of administration and, at sixty-five years old, ready to retire.

By February 1914, when Taylor left Vassar, the Trustees had not yet found a successor. The faculty, prompted by a motion in faculty meeting made by Lucy Maynard Salmon, petitioned the Trustees to be allowed to conduct their academic affairs democratically while there was no president, instead of having an acting president. This request granted, Herbert Mills was elected Chairman of the Faculty and empowered to act in important matters that would ordinarily be handled by the President. The faculty itself was empowered to appoint committees necessary to carry on faculty business. These proceedings opened the way for an enlargement of faculty influence in the operation of the College, and subsequently, with the encouragement of the next president, provided the basis for permanent faculty self-government (1). During this interlude between presidencies, students petitioned the faculty and were granted permission to form a suffrage organization. Soon after, Henry Noble MacCracken, a professor of English at Smith College, was designated President of Vassar, and early reports carried the news that he was a supporter of suffrage.

MacCracken faced a difficult situation. At thirty-five, he was young and inexperienced in administration, confronted by an assertive faculty, a student body stirring with social activism and on the other side a Board of Trustees generally convinced of the wisdom of President Emeritus Taylor’s conservative philosophy and policies. In politics, MacCracken was a progressive, by temperament a moderate, and while he generally supported the moves within the college toward democratization and self-government, as president he also felt obliged to respect the lines of institutional identity laid out by his predecessor.

At the inaugural ceremonies in October 1915, President Emeritus Taylor held a place of honor and had been asked to speak. His speech, in which he proclaimed that men’s colleges are “preparatory” while women’s are for “finishing,” must have sounded strange indeed juxtaposed against the speech that followed, by Emily James Smith Putnam, first dean of Barnard College and author of the widely read book The Lady, who startled everybody by arguing that women should become physically strong, economically independent and emotionally secure: “If I might have my way, all girls would be trained to be manly. They would be stripped of their hampering dress, which is itself the badge of physical incompetence. They would be practiced in dangerous sports, where life and limb depend on nervous control; public opinion would require of them the same standard of physical courage as it requires of boys…”

In the midst of the inaugural festivities, a group of alumnae suffrage activists (Inez Milholland among them) got permission from a College official to post notices of a suffrage rally to be held on campus. Objections were raised, and permission for the rally was rescinded. Soon after in the fall, the student Suffrage Club requested permission to have Milholland speak at Vassar. MacCracken denied the request, citing as one reason his suspicions concerning her role in the aborted suffrage rally. Though two student suffragists wrote a letter of explanation, he did not relent. Nor did MacCracken permit the Suffrage Club to invite Emily Putnam back. To this request he replied that Mrs. Putman would “hardly care to lecture twice on the subject of Feminism at Vassar in a single year.”

Soon after his arrival at Vassar MacCracken had been asked to make a statement in favor of woman suffrage, which he did, speaking, he said, strictly as a private citizen, though his statement gained a good deal of public attention. Outside of Vassar, he enjoyed cordial relations with members of the moderate wing of the woman suffrage movement, and occasionally agreed to speak for the cause. But the movement had suffered a serious split between those who wanted to pursue methods of persuasion and petition and who centered their hopes on changing the voting laws state by state or on a combination of state and federal action and those who favored more radical and spectacular means and who had decided to campaign for a federal suffrage amendment. In the fall of 1916, the student Suffrage Club again asked to have Inez Milholland come to speak. Again permission was refused. Milholland by now was clearly aligned with the “radical” element of the movement and had been campaigning against the reelection of the Democrats as a speaker for Alice Paul’s insurgent Women’s Party. In a letter to Dorothy Copenhaver on November 6, 1916, MacCracken gave two reasons for withholding his permission: first, “to approve her at this date, so soon after my accession to office would be interpreted by Dr. Taylor’s friends as a reflection on him; secondly, as one who sincerely believes in suffrage, I am forced to confess that I think [her] influence has been rather for harm than good to the cause in New York State.” It appears, then, that MacCracken opposed Milholland’s presence on campus partly because he himself was aligned with the more moderate suffrage groups and partly because his allowing “radicals” to speak at Vassar might offend the conservative Taylor loyalists associated with the College.

By 1917, the United States had entered the war in Europe, but in spite of preoccupation with war issues a campaign, ultimately successful, had been launched for a referendum on woman suffrage in New York State. MacCracken, on the Vassar campus, spoke strongly in its favor, opening a suffrage meeting in October by saying that women had earned the right to vote by “the freedom they have exercised.” He confessed that previously he had been “unwilling to engage in campaigns on this issue so long as it seemed a party issue,” but declared that “suffrage was now a national expedient–a war measure of the greatest important to… all.”

Back in May 1909 President Taylor had written in a letter to Professor Abby Leach, “some day people will look back on this excitement over the discussion of suffrage on campus]… and feel that I took the right ground in keeping out from this college the sort of radicals that unsettle all our social and intellectual values.” While President MacCracken might be said to have tried himself to keep unsettling radicals off campus, he did bring a progressive outlook to Vassar, permitting open and official discussion of political issues among the students and encouraging faculty to participate in the formation of academic policy. According to Lucy Maynard Salmon, there was more intellectual excitement and ferment in MacCracken’s first five years as president than in the previous twenty-five years at Vassar. Yet his progressivism, his stand on suffrage and his relatively liberal educational policies had so alarmed certain influential conservative Trustees of the College that in 1918 he was asked to resign. He was saved from dismissal by the intervention of faculty and alumnae (in particular, Alumnae Trustees) who rose to his defense. In consequence, the moderate reformist policies took root in the College, as MacCracken retained the presidency of Vassar until his retirement in 1946.

Footnotes

1.) The Faculty Club Report analyzed where the College stood with regard to faculty self-government and proposed the desirability of a written constitution, an extension of the legislative competency of the faculty, participation by faculty in certain Trustee committees, the forming of a committee for faculty-trustee consultation, and representation of faculty on the Board of Trustees. When it was presented to President MacCracken on February 23, 1915, he said that he liked the discussion that followed and thought it a “most profitable evening.”

Related Articles

- Abigail Leach

- Henry Noble MacCracken

- Inez Milholland

- Herbert Elmer Mills

- Lucy Maynard Salmon

- James Monroe Taylor

Sources

Material for this article was drawn from:

The MacCracken and Taylor papers, housed in VC Special Collections

MacCracken, Henry Noble. The Hickory Limb, New York: Charles Scribner & Sons, 1950.

Taylor letters in the Smith College Archives

Vassar College Faculty Minutes

Vassar College Trustee Minutes

BP and EAD, 1983

This article was originally published as “Suffrage as a Lever for Change at Vassar College” in the Summer 1983 Vassar Quarterly and presented at the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians in 1984.