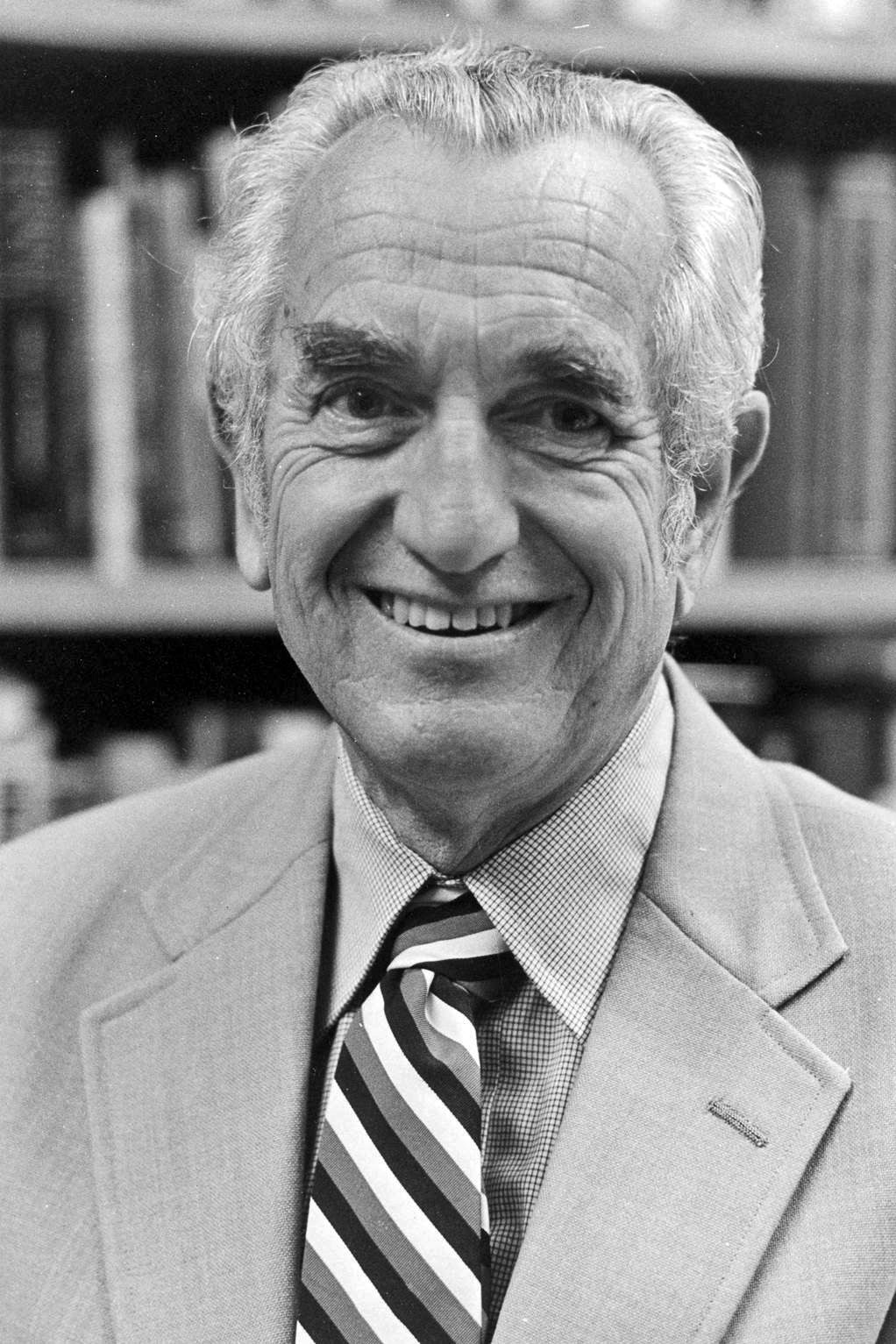

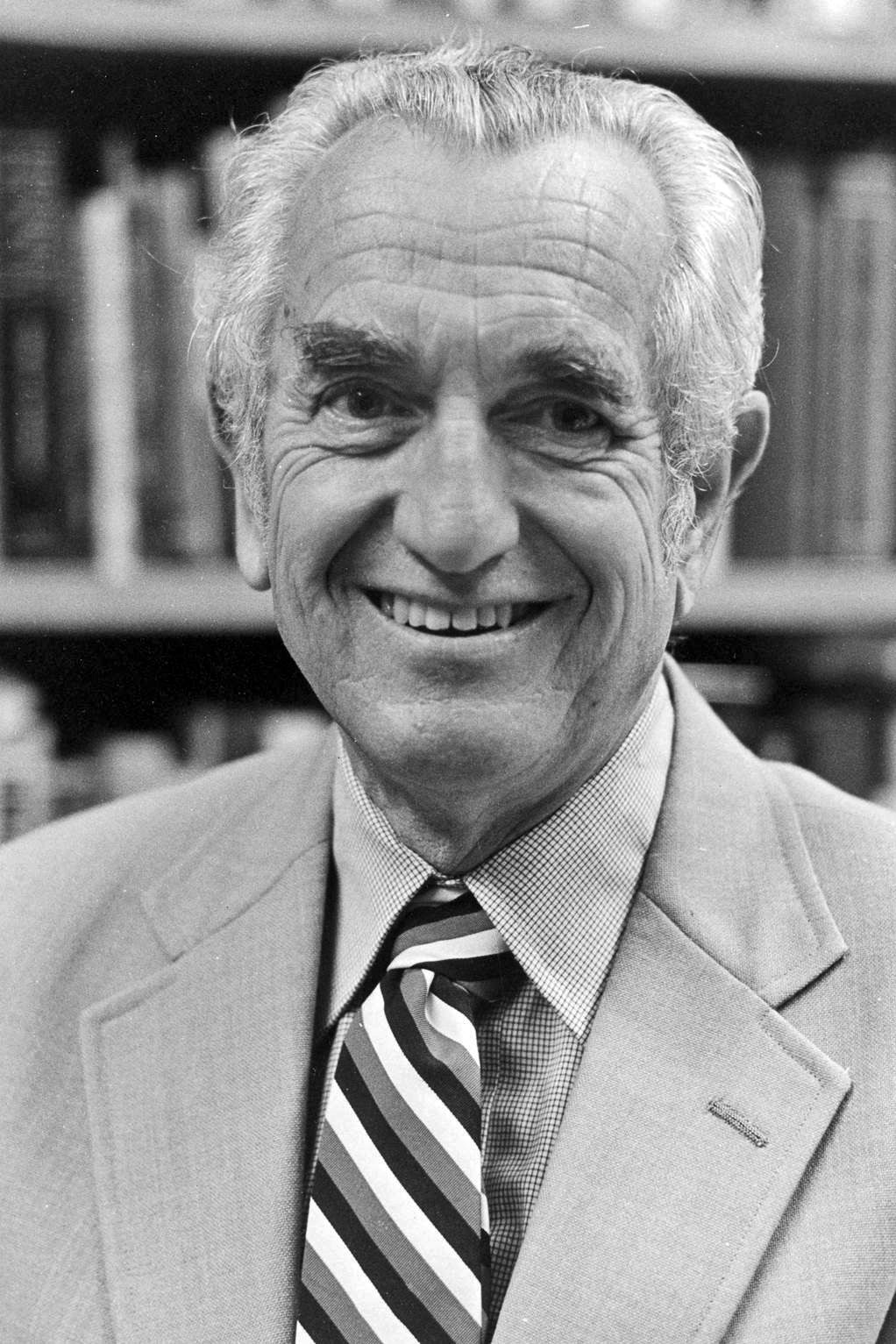

Carl Degler

“History,” Carl Degler wrote in 1981, “is heavily concerned with values, and just because it is concerned with values…history cannot have any breakthroughs comparable to those in physics, biology, or any other science.” That Degler viewed history as a modest subject would not surprise those who knew him; he was a modest man who often deflected praise in the interest of acknowledging others. “The valuable things,” he wrote of his first book, Out of Our Past, in its foreword, “are largely the result of the work of those many scholars from whom I have shamelessly borrowed.”

Carl Neumann Degler was born in Orange, New Jersey, on February 6, 1921, the son of fireman Casper Degler and Jewell Neumann Degler. He did not venture far from home for college, attending Upsala College in East Orange, New Jersey. There he took an immediate interest in American politics, becoming known among fellow students as “New Deal Degler” because of his ardent support for the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Degler received his bachelor’s degree in History in 1942, and then he waited to be drafted. Inducted later that year, he was sent to India, where he served as a weather observer for three years. He later described his service in India as a “deep learning experience,” in which he was befriended by many Indian graduate students at Calcutta University. The conversations he had with them and with fellow weather observers expanded Degler’s mind. “As a fervent supporter of FDR and the war, I had automatically accepted the relocation of Japanese Americans,” Degler wrote in 1990. His mind was changed when a fellow weather observer pointed out the racism inherent in the internment of Japanese-Americans. “What hit me hard at the time was that for all my concern for racism against blacks, I had not extended it to include Japanese-Americans.”

Returning from the war in 1945, Degler attended Columbia University for both his master’s degree (1947) and his doctorate (1952). There, he met Catherine Grady, a fellow student who was writing her master’s essay on Mahatma Gandhi. Grady had never been to the country, and the subject of India gave them much to talk about. They married in 1948, and on what he recalled as “a dark November night” the Deglers visited Vassar on what was “intended to be a brief—in fact, a very brief—honeymoon from New York City.” After checking into a small hotel in Poughkeepsie, the couple walked around the campus and attended a student performance in the Students’ Building. Degler was immediately smitten with the college. After receiving his doctorate and having taught briefly as an adjunct instructor at various colleges around New York City, he sought a position at Vassar, listing in his application American social history and the history of the American South among his teaching and research interests. He joined the Vassar history department in 1952.

In his first years at the college, Degler developed a reputation as a rigorous teacher and a tough grader—his student nickname, “D+ Degler,” suggests the high expectations he had for the students who elected his courses. Degler was nonetheless immediately popular among students—known for his expertise in leading discussions and his genuine respect for students’ opinions. An American history student, Gay Sheldon Goldman ‘60, described Degler as “highly regarded and liked by his students.” Degler was also well-respected by his colleagues—Glen Johnson, an emeritus professor of Political Science at Vassar, remembers Degler as “a fountain of information and insight.”

Degler quickly became an active member of the broader campus community. In 1954, in one of the annual faculty shows at the college, he played a monster in a parody of “Alice in Wonderland”, and in 1956 he gave the inaugural lecture for the newly formed History Club, speaking on the development of legal rights for African-Americans. He also made the acquaintance of Vassar’s President Sarah Gibson Blanding. Blanding had grown up in Kentucky, and the two bonded quickly over their passion for the American South. When Blanding instituted the house fellow system in 1953, the Deglers volunteered to serve in the new program as fellows in Davison House. This experience, according to the Miscellany News, “helped him better understand the problems of his students.” In turn, the Davison students appreciated Degler’s presence as a house fellow in expected and unpredictable ways—one commented that watching Degler wrangle his young son and daughter made her “not so anxious to have a large family.”

In 1954, under the faculty merit system Blanding helped to establish, which especially valued teaching ability, Assistant Professor Degler was promoted to associate professor after having worked just two years at the college. He was promoted to a full professorship in 1962. Early in his time at Vassar, Degler created two new history classes—History 265, “American Cultural History”, and History 362, “The History of the South”. In the preface to his a detailed history of America from its founding to the mid-twentieth century, Out of Our Past: The Forces that Shaped Modern America (1959)—his first book—Degler cited his work in “American Cultural History”: “I am indebted to the several scores of students with whom, over the years, I discussed these ideas in History 265.” The book was well-received by critics. The Mississippi Quarterly praised the book as “a delightful interpretation of U.S. history”, and the Herald Tribune wrote: “Degler has chosen to stress the role of ideas—not the ideas of the great thinkers but rather the beliefs, assumptions and values of the people.” Since its publication, Out of Our Past has become a standard text in colleges and advanced placement US History courses.

After Out of Our Past, Degler turned his attention to feminism and women’s rights. He had become fascinated by this subject after he came across the writings of early feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman at the beginning of his time at Vassar. Her thesis was that it was necessary for married women to work and have a source of income aside from their husbands in order to be truly independent—a commonplace sentiment now, but radical in the early 20th century. Degler also credited his interest in feminism to the women he taught, who “sought to learn about themselves and their future from the American past.” Degler developed an opinion, closely aligned with Gilman’s, that “the central values of the modern family stand in opposition to those that underlie women’s emancipation.” He promoted this idea throughout the 1960s, speaking at the American Association of University Women in 1962 and editing a new edition of Gilman’s Women & Economics in 1966. That same year, the National Organization for Women was founded, and Degler was, along with Richard Graham, one of only two men asked to join at its establishment.

Undertaking visiting professorships at Columbia and Stanford in the 1960s, Degler published articles which spoke to his many interests in various publications. His subjects ranged from the genesis of American racism and the varied points of view on secession and slavery in the antebellum South to the question of whether or not federal aid should be provided for parochial schools. One of his lectures at Vassar, in 1962, drew praise from several publications and demonstrated Degler’s interest in comparative history. In “The Burden & Irrelevance of the American Past” Degler argued that our unique history, without the slow evolution of self-government usually characteristic of emerging nations, had neither “fitted us nor warned us” of our international role. Goucher Weekly praised the content of the speech, the interesting and interested manner in which Degler spoke, and his responses to student queries. Degler, unsurprisingly, wanted to hear what his students had to say.

Degler’s prolific output of academic articles drew attention from many research universities, among them Stanford. In 1968, he accepted Stanford’s offer, and moved to California with his family. Professor Degler left Vassar when the institution was in a state of flux—the Vassar-Yale proposal, which involved various possibilities for what was termed “coordinate coeducation,” had been rejected a year earlier, and plans to turn Vassar into a coeducational institution were beginning to be explored. Degler later recalled that he left Vassar not because of coeducation, but because he “wanted a strikingly different as well as more comfortable location, a larger academic scene, and to be able to work with some colleagues I knew there.” Among those Stanford colleagues was David M. Potter, a fellow student of Southern history and women’s history and Degler’s friend. At Stanford, the two worked together on Potter’s book The South and the Concurrent Majority, which, edited by Degler, appeared in 1972.

An important year for Degler, 1972 was also the year that he won the Pulitzer Prize for History for his book Neither Black nor White: Slavery and Race Relations in Brazil and the United States. The book, published in 1971, is a comparative study of the relations between blacks and whites in Brazil and the United States. In the preface, Degler said his primary audience was not fellow historians, but rather “Americans who recognize that the central question of the twentieth century is whether the United States will be able to work out a biracial society in which blacks and whites will be able to live together in mutual respect and justice.” Degler believed that by viewing problems in the United States through a comparative lens, issues could be recognized as the result of circumstance rather than the inherent “nature of things.” In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, Degler’s comparative study received the Beveridge Prize from the American Historical Association and the prestigious Bancroft Prize, awarded annually by Columbia University. At Stanford, he became the Margaret Byrne Professor of American History.

Continuing at Stanford to study women’s history and teaching it, Degler returned to Vassar in April 1973 to lecture on the nature of women’s history. In the Miscellany News, Susan Campbell ’73 reported on his whirlwind visit: “Caught between an evening classroom discussion and a late cocktail party, (and probably secretly desiring to be in bed asleep more than anything else), Carl Degler graciously succumbed to an interview last Monday.” Speaking on “women in authority,” Degler recalled that the dean of faculty, the chairman of the history department and the president of the college had all been women in his early Vassar days, adding, “I am sure that dealing with women on this level has been an important factor in changing my image of the sex.” Campbell reported that Degler heartily endorsed the college’s proposed women’s studies program, and, having spoken with “various Vassar men”—an innovation from the Vassar he had known—he felt that “’Vassar has the possibilities of doing something different in helping both sexes re-realize the worth of each other.” “There must,” Degler also declared, “be a deep re-evaluation of the nature of marriage and the family…. There are men throughout the country who are saying, ‘I can’t take that job; my wife can’t move now.’ To say this, a man must be strong, and the woman must be strong enough to make him say it…. Marxism is piddling radicalism compared to feminism.”

For the academic year of 1973-74, Degler held the distinguished Harmsworth Visiting Professorship of American History at the University of Oxford, lecturing there on “Is there a History of Women?” in his first month. In the 1970s Degler also continued to write about the South; The Other South: Southern Dissenters in the Nineteenth Century appeared in 1974, and Place Over Time: The Continuity of Southern Distinctiveness followed in 1977. His fascination with women’s history culminated in the publishing of his 1981 book At Odds: Women and the Family in America from the Revolution to the Present. In it, Degler tracked the development of the modern family as women pursued autonomy to a greater extent. At Odds was notable for being one of the first books on the history of women written by a male historian.

Degler retired from Stanford in 1990. He had a long and varied career to look back on; having taught for 38 years, Degler was also president of various historical organizations, including the Organization of American Historians, the Southern Historical Association and the American Historical Association throughout the 1980s. After his retirement, Carl and Catherine Degler travelled a good deal. At the time of her death in 1998, they had been married nearly 50 years. He remarried in 2000 to Therese Baker, a sociology professor at Stanford. They remained married until Degler’s death on December 27, 2014. He was 93 years old.

Before his death, in 2008, Carl Degler published a remembrance of Vassar in American Places: Encounters With History. In it, he gave a brief history of the college, like any good historian, and remembered the topics he had pursued and the friends he had made during his time there. In conclusion, he observed:

“Vassar had done so much for me that my staying could be easily justified. But that was not the Vassar I had learned about; it sought, rather, to develop its faculty as well as its students.” True to the subject matter that he taught, Degler recognized the importance of the past in shaping the present. Degler’s experience at Vassar had shaped him into an inquisitive historian, a beloved teacher and a champion of those who did not have a voice.

Related Articles

Carl Degler’s essay, “Vassar College”

External Links

A Stanford University remembrance of Carl Degler.

Sources

Degler, Carl, “History is One of the Humanities.” The History Teacher vol. 14, no. 4 (Aug, 1981).

“World War II in the History and Memory of Carl Degler.” The History Teacher vol 23, no. 3 (May, 1990).

Williams, Wendy, “Praise Given Faculty Show of Daisydaze,” Vassar Chronicle, vol. XI, no. 24, May 8, 1954.

Marjorie Barr, “Brooks’, Deglers, Their Infants and Animals, Enjoy Fellowship,” Vassar Chronicle, December 4, 1954, vol. XII, No. 10, December 4, 1954.

Sheingorn, Carol, “Degler Elaborates on Negro’s Emergence,” Miscellany News, vol. XXXXI, no. 6, October 24, 1956.

Nathans, Elizabeth Studley, “Honoring Carl Degler,” Vassar Quarterly, vol. 111, issue 1, Winter 2015.

Biographical File, Carl Degler. Vassar College Special Collections (VCSC).

“Sarah Gibson Blanding,” Vassar Encyclopedia.

BC 2015