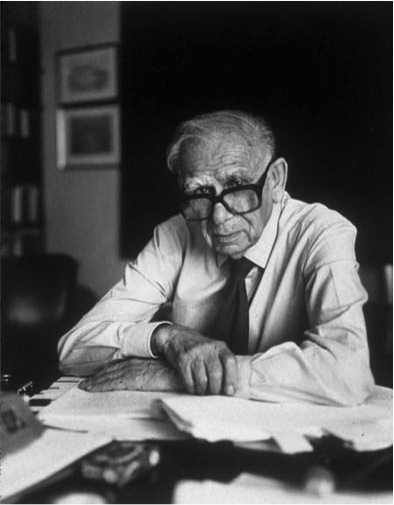

Richard Krautheimer

“I do not know what I have achieved as a teacher, if anything,” admitted Richard Krautheimer in his commencement address to the Class of 1945. “But I do know that I have enjoyed teaching…I have learned a great deal, from my blunders, and from my colleagues, and from my students.” Over 40 years later, in 1987, over 60 scholars—many of them his former students—presented essays written in Krautheimer’s honor at a dinner celebrating the renowned art historian, just one of many proofs that he had indeed achieved a great deal as a teacher.

The son of Nathan and Martha Krautheimer, Richard Krautheimer was born in the Bavarian city of Fürth in 1897. He served the Kaiser in the trenches of the First World War and entered university in 1919 to study law, at his father’s insistence. After the war, he realigned his ambitions toward art history, after attending on a whim an art history lecture. Studying at the universities of Munich, Marburg, and Berlin, Krautheimer graduated summa cum laude from the University of Halle-Wittenberg in 1925 with a Ph.D. in medieval architecture. He wrote his dissertation, “The Churches of the Mendicant Orders in Germany (1240–1340),” under the guidance of the influential medieval art historian Paul Frankl.

At university Krautheimer met his future wife, Trude Hess, a student of medieval sculpture. The couple wed in 1924, and in 1927, Krautheimer fulfilled his habilitation requirement, the highest scholarly qualification in his field. His habilitation thesis won him a post as privatdozent (private lecturer) at Marburg in 1928.

In 1933 the Nazi Party seized power in Germany, and all Jewish professors were dismissed from their duties. With his position at Marburg terminated, and sensing a grim future for Germany, Krautheimer fled to Rome. Although a refugee, he soon fell in love with Rome, which had much to offer an emerging expert on early Christian and Byzantine architecture, including a guest professorship at the Bibliotheca Hertziana, a German-funded art history research institute.

And in Rome Krautheimer conceived what would become his most engrossing work, the Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae, a scrupulous study of the city’s early Christian basilicas, dating from the 4th to the 9th centuries. Krautheimer labored on this “handbook” of sorts for much of his life, the first volume appearing in 1937 and the final one in 1977. According to architectural historian James S. Ackerman, the five-volume project “altered our conception of the setting of worship in the early Christian community.”

Visiting and minutely studying these ancient churches, Krautheimer learned the discipline of archeology as he oversaw dozens of excavations throughout the city in order to discover what lay beneath each basilica. He only wrote about a basilica once he had placed it in its historical, cultural and doctrinal context, studying not only the sites themselves but also the literature, history and symbolism of the early Catholic church. This approach to the Corpus explains its lengthy formulation and, moreover, its position today as the definitive work on this period of Roman architectural history.

But even Rome proved unsafe for Krautheimer and his wife. In 1935, through an arrangement with a London-based organization established to aid refugee scholars, Krautheimer found a position at the University of Louisville, “a place,” according to his colleague James Ackerman, “he had never heard of in a country the language of which he could not yet speak.” Krautheimer later recalled a student approaching him during his first semester at Louisville and exclaiming, “Dr. K., today I understood a whole sentence.” Many years later he admitted that English had become his language of choice; he found it more “flexible” than his native tongue.

Krautheimer’s move to Vassar came largely by chance. He met Grace McCurdy, a professor of Greek at Vassar, on an ocean line, and through her advocacy he subsequently received an offer from the college to teach art history. The chair of the department, Agnes Rindge Claflin, was eager to hire both German refugee scholars and talented new art historians: Krautheimer was a perfect choice.

The Krautheimers moved to Poughkeepsie in 1937. They lived, in the professor’s own words, “on the first hole of the golf course.” He enjoyed his position at Vassar, and he happily joined in campus activities—sitting for interviews with the Miscellany News, giving private talks, and attending arts-themed club meetings.

In 1941 he spoke at the inaugural meeting of the Vassar College Classical Society, on the topic of “The Architectural History of a City, viz. Rome.” Students recalled that he routinely sat among them in the library, recognizable by his habit of talking to himself.

At Vassar, Krautheimer entered into the perennial analysis of the ideal liberal arts curriculum. Responding in 1944 to an editorial in The Miscellany News, favoring reducing the course load from five to four courses per semester, he wrote:

Let us be frank about it; Vassar College has heretofore followed a policy of offering an education which imparted the initial stages of vocational training on the background of a broad general education. It strove towards combining both thoroughness and spread. This combination seems, in my opinion, the basis of what we call a Vassar degree.

The following year, The New York Times reported on a collaborative discovery Krautheimer and his colleague Professor of Geology A. Scott Warthin made about a sculptured madonna and child, one of the works presented to Vassar in 1942 in his memory by the family of financier and collector Felix Warburg and thought by experts to be a fine plaster cast of an early 15th century statue. The enigmatic work, about 30 inches tall, had stylistic elements dating it to France around 1400, but no original for it had ever been identified. And its features “linked it to a group of Rhenish, south German, Silesian and Austrian madonnas, the ‘beautiful madonnas,’ for which a French model had always been suspected but never found…. Furthermore, the workmanship [of the Vassar madonna] seemed too neat and clean for a plaster cast.”

Using a small chip of material taken from the bottom of the statue, Professor Warthin was able to first determine that it was unquestionably not plaster but a soft chalk in its natural state.

Fossil remains in the chip then allowed him to speculate fairly accurately where the material may have come from, and comparisons with 25 chalk samples indicated that it probably came from around Rouen, France.

“The conclusions reached by the geologist,” said The Times, “seemed, therefore, to support those reached by the art historian on the basis of historical and scientific evidence: that the statue is an original, created in northern France about 1400.”

Krautheimer enjoyed his colleagues and respected the students he taught, although he confided to The Miscellany News that he found them somewhat timid:

Students are well-prepared by artistic and intellectual backgrounds, although they sometimes have a hard time getting used to the idea that there ever have been a couple of decent painters after Raphael. They are scared as soon as they see a Miró.

He expanded this theme in his 1945 commencement address:

For while liberal education is a serious business, one of its aims is to help you enjoy life: you may not have believed it when you were taking an Art 105 slide quiz, but it is still true. I for one would not like to go through life without being able to enjoy the Sistine chapel or a mobile by Calder, the “Divine Comedy,” or Machiavelli’s “Pincipe,” “The Tempest” or a concerto by Monteverdi. Life without fun is not worth living, and intellectual pleasures are not the worst.

As war broke out in Europe and as it engaged the United States, Krautheimer—a German émigré with a very German-sounding surname—was asked to aid his host country. Because of his architectural knowledge, he was called to Washington, D.C. a number of times: once in 1941 for a roundtable conference on the preservation of American monuments, and again in 1943 for a special assignment with the Office of Strategic Services. The government needed help analyzing aerial photographs of Rome, so that the military could try to avoid important historical sites during bombing missions. Krautheimer took a year’s leave from Vassar to aid in this effort.

Becoming U.S. citizens in 1943, in 1947 he and his wife returned to Rome for the first time in a decade: “We loved it,” he reported to the Miscellany News. Krautheimer was particularly touched by his reception at the Vatican Library. “Haven’t seen you for a little while, Professor,” said the attendant at the front desk. “It was,” Krautheimer said, “as if there had never been a war.” On this trip, Krautheimer began his most famous excavation: the basilica of San Lorenzo Fuori Le Mura in the Tiburtino district of Rome—the only Roman church to be damaged by Allied bombings, thanks partly to Krautheimer’s work with the U.S. government.

San Lorenzo’s damages proved a blessing in disguise for Krautheimer and the archeological world. Excavation of the severely damaged building revealed that the church was much older than anyone previously thought, dating back to the third century. Sponsored by the Pontifical Commission on Sacred Archeology, Vassar College and the American Philosophical Society, the excavation, he later said, “clarified the early history of the basilica.” Describing the unearthing the ancient relics, said: “As light began to play on the glowing surface, the beautiful figures seemed to come alive against an undulating ground after the centuries-old layer of dirt and grime were removed.”

After 15 years, Professor Krautheimer left Vassar. He had lectured part-time at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University since 1938, and in 1952 had decided to teach full-time in New York. In his letter of resignation to President Sarah Gibson Blanding, he wrote:

My decision has not been made with an easy heart… and my reason for leaving Vassar and going to N.Y.U. is solely that it will give me a chance to train graduate students and to educate a small group of architectural historians who are badly needed at this moment.

In 1956, he and his wife jointly published Lorenzo Ghiberti, a detailed study of the Renaissance artist and creator of the “Gates of Paradise,” the bronze doors on the Baptistery in Florence. Krautheimer dedicated most of the following decade to Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (1965) for the Pelican History of Art series. “This book was difficult to write, and I can truthfully say that I have never faced a harder task,” wrote Krautheimer in the preface. “The reader will have to decide whether or not I have succeeded.” The Society of Architectural Historians praised the book, awarding Krautheimer the coveted Alice David Hitchcock Award. Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture today enjoys the status of a “classic” in its field; the fourth edition was published in 1992.

After training a generation of architectural historians, Professor Krautheimer retired in 1977. But he continued writing prolifically and exploring Rome, where he spent most of his later years. Among all his accolades and awards, he treasured most the honorary citizenship awarded him by the city of Rome in April 1994. Krautheimer was descending into excavation pits until a year before he died, and he was in the midst of planning his 100th birthday celebration when he died—on November 1, 1994, at 97—at the Palazzo Zuccari in his favorite city in the world.

Sources

Krautheimer, Richard. Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. 4th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992

James S. Ackerman, ”Biographical Memoirs: Richard Krautheimer.” Proceedings if the American Philosophical Society, 148, no. 2 (June 2004).

James S. Ackerman, et al., “In Memoriam: Richard Krautheimer (1897–1994).” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 54, no.1 (March 1995).

Jessie Butler ’46, ‘Statue Considered Plaster Imitation Was 15th Century French Original, The Vassar Chronicle, September 8, 1945.

Virginia Lewisohn ‘49, “Krautheimers Find Italian Youth Spirited; Discuss Political and Economic Conditions.” The Miscellany News, October 15, 1947.

Elspeth McClure ‘44, “Popular Professor’s Special Field is Early Christian, Byzantine Architecture.” The Miscellany News, April 22, 1942.

Krautheimer, Richard, biographical file. Vassar College Special Collections:

ALS to Vassar College President Sarah Blanding, April 5, 1952.

Commencement Address to Class of 1945.

Letter to the editor. Vassar Chronicle, December 2, 1944.

Sorensen, Lee, “Krautheimer, Richard.” Dictionary of Art Historians,

www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/krautheimerr.htm

PB, 2012