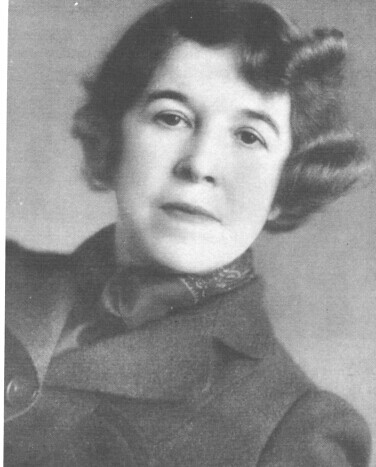

Hallie Flanagan Davis

Hallie Ferguson was born in Redfield, South Dakota, on August 27, 1890. As a young child, she and her siblings would stage dramatic productions in the family living room. Little did anyone suspect that the tiny Irish girl from the Midwest would grow up to become one of the leading forces in early 20th century theater.

At the age of ten, Hallie moved to Grinnell, Iowa, with her family. She entered nearby co-educational Grinnell College with the class of 1911. There she majored in Philosophy and German, and participated in the dramatic club. After graduation, she married her college sweetheart Murray Flanagan, also a member of the Grinnell dramatic club. The newlyweds moved to St. Louis, where Murray worked in insurance, and his wife focused on raising their two sons—Jack, born in 1915, and Frederick, in 1917. They soon moved to Omaha, Nebraska, where Murray was diagnosed with tuberculosis. While her husband languished in a Colorado Sanitarium, Hallie moved back to Grinnell and began teaching drama at the college, with frequent trips west to Colorado. Murray died in 1919, and Hallie was left a widow with two small boys to raise. Tragedy struck again when Jack died of spinal meningitis in 1922.

Soon after her son’s death, Hallie took Frederick and moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she enrolled in George Baker’s famous Workshop 47 dramatic production studio (which later moved from Harvard to New Haven, CT, and became the Yale School of Drama). Baker was so impressed with her work that he named her the director of the workshop’s actors’ group in 1923. By this time, Henry Noble MacCracken, the president of Vassar College and dramatic scholar and thespian himself, had caught wind of Flanagan’s potential. MacCracken was hoping to start an experimental theater at Vassar, and Gertrude Buck, the late professor of dramatic literature, had acquainted him with Baker’s workshop, which she had attended as well. Persuaded by MacCracken and promised a $3,000 yearly salary with a raise of $100 the next year, Hallie Flanagan completed her M.A. at Radcliffe and began teaching at Vassar the next fall.

At that time, courses in drama were taught under the English department, as plays were thought fit only for scholarly study, not for actual production. The college didn’t even have a theater at the time—Hallie and her D.P.s (as drama students were called) had to make do with the college assembly hall and the amphitheater overlooking Sunset Lake. Flanagan’s official title was “Director of English Speech.” She drew up plans to create an independent major in drama, but her ideas were rejected, though she did manage to institute a few dramatic production courses.

Before she began her second year of teaching, Flanagan became the first woman awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed her to travel around Europe for fourteen months studying the modern theater. She took a leave from her teaching duties during the 1926–1927 school year. While traveling in Europe, she met and befriended many of the greatest playwrights of the age, including Lady Gregory, Konstantin Stanislavsky, and Luigi Pirandello. Flanagan was most impressed with the Russian theater, and the Russians were equally impressed with her, claiming that she “understood them” and was one of their own. Her friendship with Russia would later cause her trouble.

Flanagan would eventually write a book, Shifting Scenes of the Modern European Theater, based on her travels. In the meantime, she returned to Vassar in 1927 full of enthusiasm and vigor for the theater. The first play she produced with the Experimental Theater was Anton Chekhov’s “A Marriage Proposal,” using different styles for each of the three acts: the first was done as Chekhov called for, the second, in an expressionistic style, and the third using Meyerhold’s Constructivist techniques. The play was a success, and Flanagan went on to direct many more plays at Vassar, including the world premier of T.S. Eliot’s “Sweeney Agonistes” in 1933, the American premiere of Pirandello’s “Each in His Own Way” in 1930, and Euripides’ “Hippolytus” in the original Greek in 1931. The part of Hippolytus was played by Philip Davis, professor of Greek, who also helped to direct and coach the other actors. Many suspected a romance between Flanagan and the widower Davis.

Their suspicions were correct. In 1934, Davis was on leave in Athens, and Flanagan left Poughkeepsie to visit him. Shortly afterwards the news came that they had married on April 28th. Frederick now had a stepfather, and Davis’s daughter Helen and twins John and Joanne had a stepmother. They moved into 12 Garfield Place, not far from the college, upon their return to Poughkeepsie.

The next year Flanagan (still using her first married name professionally) was appointed Director of the Federal Theater Project (FTP) under the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The FTP was created under the direction of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a former Vassar College trustee, to provide work for the thousands of theater workers left jobless by the Depression. Flanagan took yet another leave of absence and split her time between Poughkeepsie, Washington, and traveling. With a $7 million budget, she quickly hired almost all the theater workers who were eligible under the law. By late 1936, she had hired 12,500 employes across 28 states and the District of Columbia. In New York City alone the FTP played (at reduced prices) to weekly audiences of 350,000, many of whom had never seen live theater before.

Within a few years, however, the FTP was in trouble. Those in Washington suspected Flanagan of having Communist ties, mostly because of her friendships with Russians formed in her Guggenheim travels. Charles Walton, a New York stage manager, testified to the Dies (House Un-American Activities) Committee in 1939 that “the set-up of the whole arts (projects) is nothing but a very clever fence to sow the seeds of communism.” Flanagan vehemently denied these accusations in an open letter to Clifton Woodrum, Chairman of the Appropriations Sub-Committee, but to no avail. The FTP was shut down in July 1939, and Flanagan remained in Washington to tie up some loose ends. In November, she received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to supervise work on “theater research based on the FTP.” Her book Arena, a history of the FTP, came out of this research.

Meanwhile, things were happening at Vassar without Flanagan. She had tried several times to convince the Curriculum Committee to approve an independent major in drama, but she was continually blocked by Dean Mildred Thompson, with whom she shared a mutual animosity. In 1939, when Flanagan was absent from Vassar, a plan for a separate major was approved, and the Drama department was founded.

Hallie was clearly hurt by this snub, and when Phil Davis died in 1940, there was no longer anything to tie her to Vassar. She took a three-year leave of absence from Vassar to serve as acting Dean at Smith College, and in 1945, the same year she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, announced her decision to remain at Smith permanently. In 1946 she relinquished her deanship and was named Professor and Department Chair of Drama. In 1948 she wrote one of her most famous plays, “E=mc2: A Living Newspaper About the Atomic Age,” which was first performed by the ANT Experimental Theatre Series in New York City.

Flanagan went on leave from Smith in 1953 and officially retired to Poughkeepsie in 1955. She was recognized many times for her contributions to modern theater, including an honorary degree from Williams College in 1941 and the first National Theater Conference Citation award in 1968. Flanagan spent the last few years of her life in nursing homes and died on July 23, 1969 in Old Tappan, NJ.

Writing in The New York Times at the time of her death, the eminent actor and director John Houseman recalled Hallie and the “assassination” of the FTP:

Those of us in the theater will remember her for those three fantastic years in which she and her collaborators turned a pathetic relief project into what remains the most creative and dynamic approach that has yet been made to an American National Theater.”

Related Articles

External Links

Sources

Kiesel, Margaret Matlack, “Hallie Flanagan,” Iowa Woman Magazine, Winter 1983

Grinnell Magazine, November-December 1978

“Hallie Davis Given Award for Service to the Stage,” New York Times, March 11 1968

“Hallie Flanagan,” Vassar Alumnae Magazine, December 1969

“Five on Smith Faculty Retire in June,” Springfield Mass. Republican,” May 15, 1955

“Hallie Flanagan Named Dean of Smith College,” Herald Tribune,” December 11, 1941

Seattle Post–Intelligencer, November 10, 1939

Cincinnati Times-Star, July 13, 1939

“Hallie Flanagan, Director of WPA Theater, Sends Open Letter to Congressman Woodrum,” NY Daily Worker, June 18, 1939

Cowles, Rita “Little Woman with a Big Job,” The New York Woman,” March 13, 1937

Bromley, Dunbar “Mrs. Flanagan Has Job to Put 7,000 to Work” NY World Telegram, January 16, 1936

“Two Professors at Vassar Wed,” Poughkeepsie Evening Star, April 28, 1934

“Iowan Awarded Fellowship for Study of Drama,” Des Moines Register, April 20, 1926

Sprinchorn, Evert “Stagestruck in Academe,” Vassar Quarterly, Spring 1991

Houseman, John, “Hallie Flanagan Davis, 1890–1969,” The New York Times, August 3, 1969

JD 2005, CJ 2010