The Library

The Library

Sixty years ago Emily Litchfield Knapp ’32 said in her appreciation of Vassar’s Frederick Ferris Thompson Memorial Library, “I can remember with pleasure the many hours I spent prowling around in the stacks in the Libe discovering and reading many books, a number of which had little or no bearing on any particular course I was taking. . . . I bless Vassar for the open shelf Library. It is an open invitation to self education as distinguished from assigned class work.” While not every Vassar student can claim to have accepted that “open invitation,” most graduates can attest to the immense volume of intellectual work done within Thompson Memorial.

For the college’s first forty years, its collection of books moved around Main Building. In September 1865, when Vassar opened, the library was located on the third floor of Main, directly opposite the Chapel. Then a mere thirty by thirty-five feet in area, the library contained about 2,400 volumes. Eunice D. Sewall was established as the college’s first librarian in 1866, a position she held for eight years. The recollection, in 1908, of Sewall’s successor, the former music and English teacher, Frances Wood, sums up the foundational years of the library well: “There was not much of method and system to go by in those early years, [but] still Vassar not only compared favorably with the libraries of other colleges, but had some points in its favor, noticeably in number of hours open, with free use of books without charge to the student.” Even in the first years of the college’s history, the institution ensured that its collection would be widely accessible to all of its students.

Matthew Vassar’s will was a testament to the college’s investment in a comprehensive and reputable library. Speaking to the Board of Trustees in 1861, he had already made clear his wish that the college’s funds (provided largely out of his own pocket) be safely invested in the expansion of the college, and especially in “the replenishing and enlarging of the library.” When Vassar died in 1868, he dedicated part of an annual $50,000 fund to that cause. In order to relieve crowded conditions for a rapidly expanding collection of books, some of this money was allocated in 1872 to the relocation of the library to an adjoining room on the third floor in Main. The Vassar Miscellany, however, reported immediately that the new room was “poorly ventilated and only half of the would-be readers can enter. Those inside can scarcely thread their way out through the crowd.”

In 1874, the collection of volumes—now numbering nearly 9,000—was relocated again, this time to a larger room on the fourth floor corridor of Main. The long, high-domed room was a much better fit for the rapidly accumulating volumes. President John H. Raymond’s report for the 1874/75 academic year declared: “The Library in its new quarters seems almost doubled, from the more adequate display of its contents; while the beauty of the spacious room, the ample supply of pure air, the sufficiency and convenience of the furniture, render it one of the most attractive spots in the College.” In 1880, a separate Reading Room for newspapers and periodicals was established in Main.

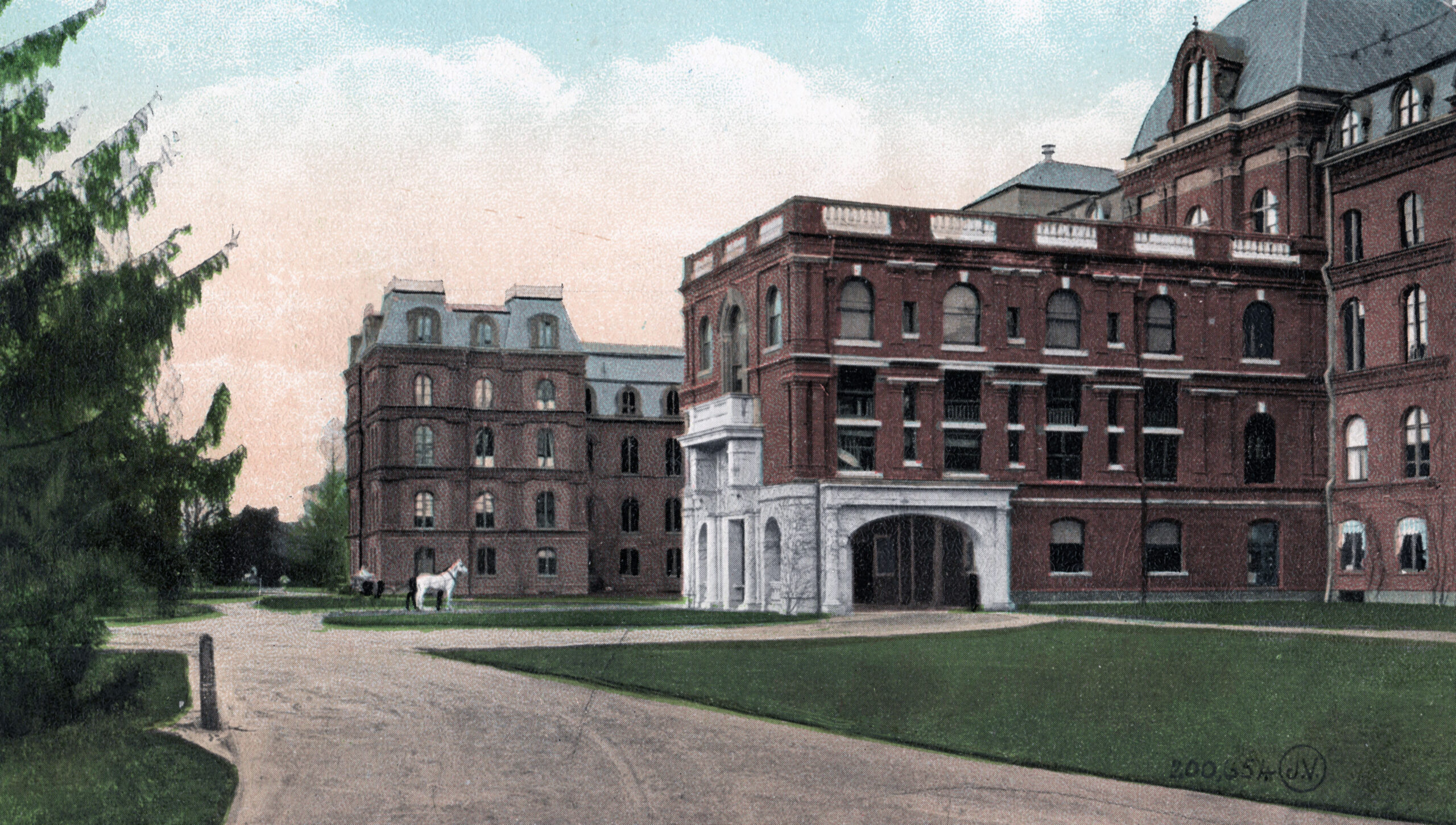

By the end of that decade, the number of volumes in the library had grown to nearly 20,000, and the student body was growing rapidly as well. In order to accommodate, the College announced in April 1891 the construction of a three-story annex, extending from the front of Main, that would house a new library. This project was financed by Frederick Ferris Thompson, a philanthropist and trustee of the college known to the student body as “Uncle Fred.” The annex was the largest of several gifts that Thompson bestowed upon the college—others included a swimming pool and a chartered steamer to give the students a trip to West Point. Many of these endeavors were financed by Mr. Thompson through a “Good Times Fund,” which spoke to the good humor of the man whose annex would take on a suitably flippant name: “Uncle Fred’s Nose.”

Construction on the annex was completed in 1893, with space for several thousand more volumes. Francis R. Allen, the architect for Thompson’s 40-room mansion in Canandaigua, New York, and for Vassar’s first residence hall, Strong House (1893), designed the project. The annex included a porte-cochere built out of veined white marble, which served as the remodeled entrance of the building. Because of the marble’s dazzling, white brilliance, the annex quickly became known among students as “The Soap Palace.” President James Monroe Taylor enthused that “the new library is even more than was hoped. It proves a most delightful place for study, is admirably lighted and ventilated, and its alcoves are far more attractive than the more crowded spaces of the old library. It has room enough for many thousand books yet!”

Those many thousand books were added to the College’s collection more quickly than anticipated, and after a few years the crowded conditions returned. The president sought an entirely new building to house the library, as the sheer volume of books—numbering over 30,000 by the turn of the century—had clearly grown too large for Main Building. At the Founder’s Day celebration in 1902, Taylor announced that a donor—whose name he withheld—would be financing a new library building for the college. Taylor revealed the next month that this donor was Mrs. Mary Clark Thompson ‘93, the widow of Frederick, who had passed away in 1899 and to whose memory the new library was to be dedicated.

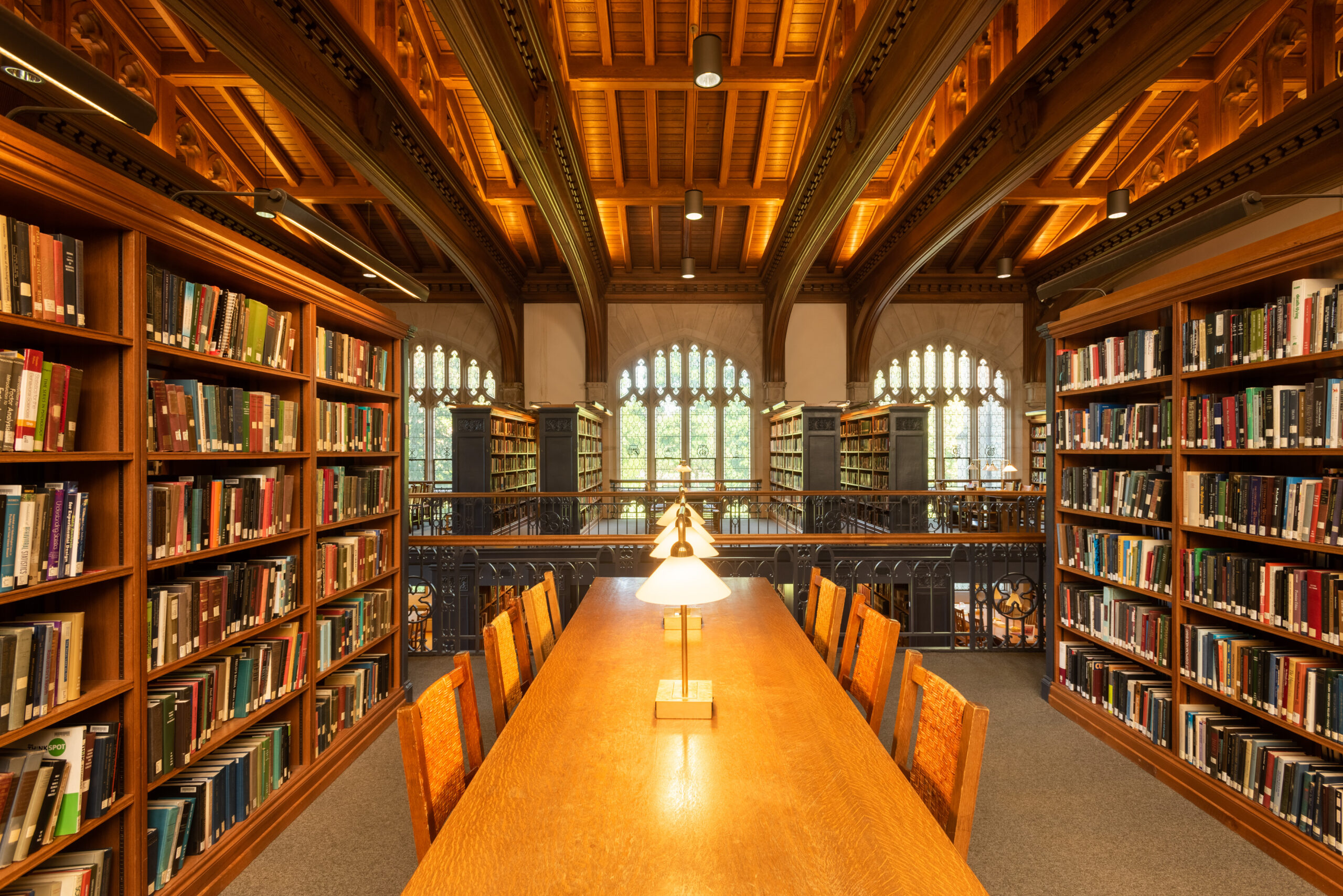

Ground for the Frederick Ferris Thompson Memorial Library was broken in the spring of 1903. Frances R. Allen and his partner Charles Collens, the architects on the project, conceptualized the building as three wings—west, north and south—built around a central tower. They chose Germantown granite and Indiana limestone to give the library a soft color-tone. The design, in the Perpendicular Gothic style, included elaborate carvings on both the interior and the exterior. Several college seals are carved into the walls of the library vestibule, assembled in a stone frieze. Among these seals are those of Cambridge, Oxford, Harvard, Yale, Smith, Wellesley, Bryn Mawr and Vassar—all proof of what the Vassar Chronicle called a “very active Good Neighbor policy.”

Though the library may have the seals of other colleges etched into its walls, the overall building is a monument to Vassar. Mrs. Thompson’s crest is also carved into the library walls, and the stained-glass Cornaro window, situated at the end of the central room in the west wing, is perhaps as emblematic of the school as Main Building itself. A gift from Mrs. Thompson, the window depicts the bestowal of the first doctorate ever to be received by a woman, Elena Lucretia Cornaro Piscopia, at the University of Padua in 1678. The central panel shows Lucretia defending her thesis before a wide array of university officials and Venetian senators. Natasha Leof, writing for the Miscellany News in 1984, explained the significance of the window: “Words, colors, symbols and composition combine to inspire the female Vassar student, or any other women with academic aspirations.” The window has inspired—or at least provided a source of light to—several generations of Vassar students, and several more to come.

The new library building was dedicated on June 12, 1905, and at the opening ceremony the choir staged a surprise performance of “Hail to Spring.” Virtually everybody on campus was pleased with the new library. President Taylor proudly stated prior to the opening: “Nothing that the Librarian could ask has been denied, and nothing that science or art could suggest has been withheld. The building, noteworthy among the finest college buildings of the land, is…a worthy center for the intellectual life of the College.” Writing in March 1908, the librarian Frances A. Wood declared that “it is like a dream fulfilled of adequate room to work in with beauty and harmony of arrangement beyond any dream of the early years.” With the addition of the Thompson Memorial Library, it seemed that Vassar had finally found a library worthy of the college’s dedication to learning.

As Vassar’s prestige matured in the early 20th century, so too did its acquisition of books. By 1914, the collection had grown to 81,000, all selected by the faculty of the college. It was agreed that the library would need another expansion, and in March 1917 the ground was broken for two L-shaped wings on the north and south sides of the library. Mary Clark Thompson ’93 was again the donor, and Allen & Collens were retained as architects. The support for the project was not as widespread this time around, as students feared that the extensions would mar the beauty of the library. The librarian at the time, Amy Reed ’92, gently allayed these fears in a Miscellany News article: “Members of the college who last year viewed the rising walls of the additions to the Library with some natural doubts lest these might prove merely unsightly excrescences on a beautiful building, must have been pleasantly disappointed at their first sight this fall of the exterior now almost completed.” The additions, constructed at the back of the building, maintained the Perpendicular Gothic style and were hardly visible from the front. The Library additions opened on Founder’s Day in 1918, and over the summer the college’s 100,000 books were re-ordered to best utilize the space.

Mary Clark Thompson ’93 died in 1923, five years after the library she funded was expanded. In her will, she left $300,000 to Vassar for the upkeep of the library and the acquisition of new books. Half of that money was allocated to a new project in 1935, which would connect the south wing of the library to the nearby Taylor Gate, built along with Taylor Hall in 1915 as a tribute to James Monroe Taylor, who had retired in 1914. A $150,000 gift from the Carnegie Corporation was also used to fund the project, which was designed by Charles Collens, from Allen & Collens. President MacCracken made clear that the purpose of the addition would be to “increase the resources of both the Library and the Art Department.” The new space would house three floors of book stacks, as well as several study and conference rooms and a new Art Library.

The addition was named the Van Ingen Library, in honor of the first art professor at Vassar, the Dutch painter Henry Van Ingen. The new library was dedicated on October 15, 1937. Although the exterior of the building maintained the Perpendicular Gothic style, the interior was decidedly different from Thompson Memorial. It was designed in a modern style, with glass brick walls and minimalist design. John McAndrew, assistant professor of art at Vassar and the first curator of architecture and industrial art at the Museum of Modern Art, and New York designer Theodore Muller were responsible for the design. Van Ingen not only added a modern embellishment to the Library, it also doubled its shelving capacity—400,000 books could now be comfortably housed.

The library saw its next major renovation in 1960, when Thompson Memorial was updated again. The Library staff began accumulating recommendations for the building’s improvement in 1957, with input from the Student Curriculum Committee and faculty members. The most salient recommendation was to decrease the travel distance for patrons seeking books, a goal achieved by filling in the two interior courts formed by the 1918 wings. These areas were transformed into stack areas for books, as opposed to courtyards that had to be circumnavigated. New stairs and an elevator to all three floors of the building were added to increase accessibility.

Perhaps the most important addition, however, was the Special Collections seminar room added to the lower floor of the Library. This space would give all Vassar students a chance to engage with the college’s collection of rare books and manuscripts—including such gems as the journals of John Burroughs and John James Audubon’s Elephant Portfolios. The Special Collections seminar room was completed a few years after the renovation, in 1964, as it had to be installed with a complex humidity control system in order to preserve the often fragile materials. Students anticipated the completion of the new room: Marsha Asofsky ’65 wrote in the Miscellany News that the project “will be one of the most anxiously awaited additions to the enlarged Vassar library. The room will provide a place of study for students using rare books, previously housed in a subterranean corner of Rockefeller Hall.” Display cases holding rare materials along each wall of the room increased student interest in the library’s newest addition.

In 1971, Vassar received a $6 million bequest from Helen D. Lockwood ’12, a former chair of Vassar’s English department. Lockwood had left the money for the betterment of the school, and the Board of Trustees decided that part of the bequest should be used for another addition to the library. The latest addition would be an L-shaped wing in a more contemporary styled that would be accessible off of the Library’s north room, and house a 24-hour study room and typing space, as well as a new rare book room and new stack areas. A new air-conditioning system was also planned, bringing cooled, fresh air to the entire library complex.

President Alan Simpson broke the ground for the Helen D. Lockwood extension on November 13, 1974. Helmuth, Oban & Kassabaum were the architects for the 32,000 square foot project that was planned to be architecturally congruous with the rest of the building.

The plan for the Lockwood library was met with a warmer reception than a proposal for an almost all-glass extension submitted earlier in the decade, as people were skeptical about the upkeep of a predominantly glass building. The architects planned to utilize a blend of glass and limestone for Lockwood, to blend with the old stone of the library. The Helen D. Lockwood extension was opened in September 1976, to a warm—if not passionate—reception from students. Campus feelings toward the extension were summed up in a Miscellany News article from May 1977: “Whatever its aesthetic appeal, the addition has provided much needed space for mind-expansion.”

The next decade was most noteworthy not for what was added to the library, but rather, what was taken away. In February of 1982, a disgruntled student broke into the library reserve room and removed approximately 6,000 volumes. He did this in protest of the administration’s neglect of the college’s Shakespeare Garden, and left a note on the door of the reserve room: “If you ever want to see these reserve books again, you will begin planning the complete restoration of the Shakespeare Garden immediately.” The note was signed “Timon of Athens,” which, a reporter for Vassar Quarterly pointed out, was the name of a Shakespearean character “who is portrayed as a misanthrope and a recluse.” The books were found shortly after they disappeared, in a nearby room in the library. A student, who paid a fine and posted a public apology, admitted to the prank after the books were restored.

The beginning of the ‘90s was also characterized by another library mystery. An oil painting of Alan Simpson, which had been stolen from the Helen D. Lockwood extension over a year earlier, was mailed back to The Miscellany News in 1990. According to the newspaper, “the painting had been removed from its frame (still missing) and mailed to The Misc with a New York City postmark and no return address.” The culprit was never discovered, nor was the frame.

The library saw a return to normality later on in the decade, with the announcement of another extension in March of 1996. The new library renovation project was funded by the Campaign for Vassar, a $200 million fundraising campaign the college had begun in ’93. The project included the construction of a new, 33,000 square-foot building, as well as a renovation of the existing library. The new addition would be named for Martha Rivers Ingram ’57, a Vassar trustee who had served on the Campaign for Vassar, as well as for her late husband. The Martha Rivers & E. Bronson Ingram library extension would be adjacent to the north wing of the library and in front of the Lockwood addition, giving the latter building a new face. Construction on the $20 million project began in the summer of 1997.

One of the goals of the renovation, according to Capital Project Manager Bob Fischman, was to “clean up the physical circulation within the building and make it clearer where things are.” The new update was reminiscent of the 1960 renovation, which also set out to make the library an easier space to navigate. President Frances D. Ferguson addressed the current overcrowded state of the library in her remarks at the ground breaking ceremony: “The interior of our Library is a bit of a jumble: parts don’t connect, logic is hard to discern, and, if you are a newcomer, you need a ball of string to track your route. The new Martha Rivers and E. Bronson Ingram Library will bring light and order to this situation: adding space, clarifying the passage from part to part, fulfilling critical library needs, and integrating externally the style of Thompson, Lockwood, and Ingram with their architectural neighbors. It will, in short, meet some long felt needs.” Some of these “library needs” were a reading room, a reserve desk, and a new home for Special Collections. The most precious materials of the college would now be housed in the Catherine Pelton Durrell Archives and Special Collections, which would include a rare book room as well as teaching and reading areas.

The new addition to the library was dedicated in May 2001, and was a hit among students. A profile of the renovation was included in Vassar Quarterly in September of that year: “With its high-tech information resources, bright and airy study spaces, convenient and expansive reserve and periodicals rooms, and a new home for the Vassar College Archives and Special Collections, the Martha Rivers and E. Bronson Ingram Library—the newly minted addition to the Vassar College Libraries—was a popular and much used academic center even before its official dedication in May.”

Related Articles

Ron Patkus on Vassar Special Collections

Sources

Asofsky, Marsha. “New Seminar Rooms Houses Rare Books, Exhibitions,” The Miscellany News, vol. XLIX, no. 3, October 7, 1964.

Benezet, Barbara. “Glancing Back at Coeducation with a Prejudiced Perspective,” The Miscellany News, vol. LXV, no. 13, May 6, 1977.

“Books Transplanted,” Vassar Quarterly, vol. LXXVIII, no. 2, January 1, 1982.

Leof, Natasha. “Celebration in Glass,” Womanspeak, vol. 6, no. 2, May 1, 1984.

Mooney, Joan. “Library Plans Call for Changes,” The Miscellany News, vol. LXI, no. 7, April 4, 1975.

O’Connor, Acacia. “20 Years at the Top,” The Miscellany News vol. LXXX, no. 21, April 28, 1991.

Reed, Amy L. “A Growing Library,” The Miscellany News, vol. II, no. 2, October 3, 1917.

Rosenberg, Ilsa. “Vassar Soap Palace is Falling,” The Miscellany News, vol. XXXXIV, no. 19, March 2, 1960.

Winum, Jessica. “Inspired Addition: Vassar’s Library,” Vassar Quarterly, vol. 97, no. 4, September 1, 2001.

Wood, Frances A. “The Brindle Cow,” The Miscellany News, vol. XXXVII, no. 6, March 1, 1908.

Subject Files, V.C. Libraries. Vassar College Special Collections (VCSC).

BC 2017