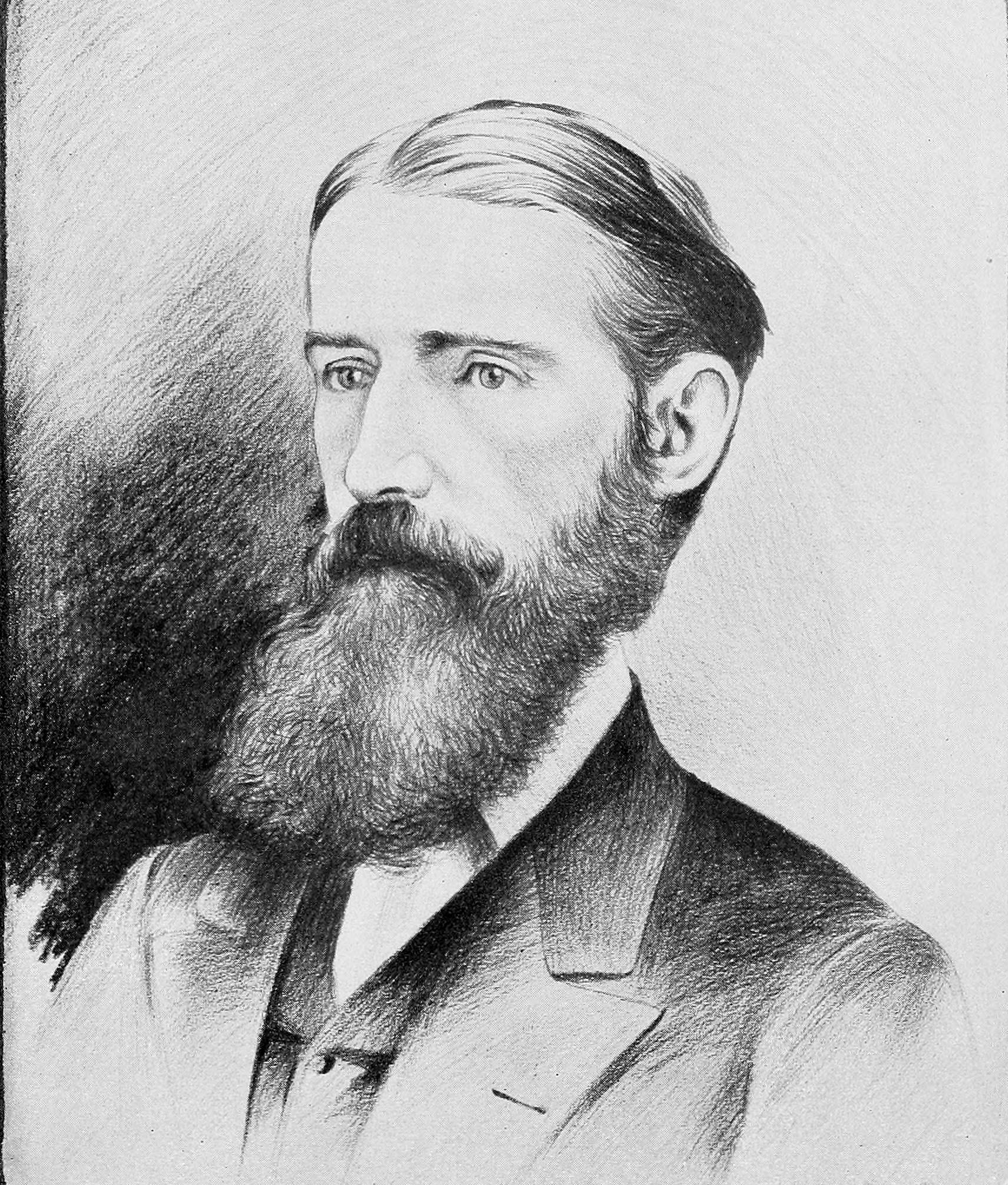

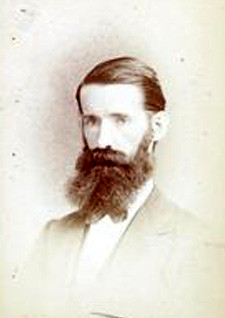

James Orton

“In this day of many voyages, in the Old World and the New, it is refreshing to find an untrodden path.”

Source: Edward Albes (July 1914). “An Early American Explorer”. Bulletin of the Pan-American Union 39 (1): 5.

The first sentence of Professor James Orton’s preeminent work, The Andes and the Amazon, is a perfect introduction to Orton’s life, work and personality. Orton was born on April 21, 1830, in Seneca Falls, New York, the fifth of eight sons of Dr. Azariah Giles Orton. A dedicated Protestant minister, poet, and classicist, Dr. Orton, as his granddaughter noted, “knew practically nothing of the family finances; consequently none of the boys had the vigor of normal children and several died very young. In spite of real poverty, however, they were brought up in great refinement….”

When James was 13 one of his teachers introduced him to the world of the natural sciences, inspiring in him a deep love of chemistry, and later mineralogy. James and his brothers took to the woods surrounding their home, collecting living specimens of plants, insects, and minerals, which they studied in the laboratory they built for themselves in the basement of their home. His sister Susan would later recall that “James seemed never to tire of performing experiments, and while other boys of his age were at play, he might be found in his workshop, or in his father’s study pouring over the classics, or searching the woods and fields for minerals and flowers.”

At 16 James was writing both poems and scientific articles based on his experiments, and at 17 he and two of his brothers were sent to school in Oxford, New York, where, due to their family’s financial condition, they “lodged in the basement and boarded themselves.” He excelled in his studies despite his family’s disadvantages and continued his pursuit of scientific understanding. Also that year, Orton submitted the idea for his first invention, a device that would improve the functioning of the Leyden jar, to Scientific American. Devised in the 18th century, the Leyden jar was an early form of capacitor—a glass jar lined inside and out with tinfoil and having a conducting rod connected to the inner foil lining and passing out of the jar through an insulated stopper. Although the journal’s editors did not publish Orton’s article, they hailed his invention as a “valuable” idea. This first attempt at publication also sparked a correspondence and a friendship with Scientific American’s editor, Rufus Porter, which would last for the remainder of Orton’s life.

Later in the same year, Orton submitted a scheme for adapting for use in lighthouses of the “Drummond light,” the high-intensity light of incandescent lime or “limelight” developed by the Scottish engineer, surveyor, and statesman Thomas Drummond (1797–1840). Scientific American published a sketch and brief explanation of the invention, calling it an “ingenious method.” James’s relationship with Scientific American continued to blossom, and the journal published twenty-one of his articles on mineralogy and entomology between 1849 and 1853.

The following year, undaunted by his failure to secure publication of his first comprehensive work, a dictionary of scientific terms, Orton set out on a personal excursion, walking from Oxford, New York to Syracuse in order to see a locomotive for the first time. He later described the experience as one of the most important and meaningful in his adolescent life. Rejuvenated, he returned to his work, and at 19 he published his first book The Miner’s Guide and Metallurgist’s Dictionary. Coinciding with the California gold rush, the book was a surprising success, later appearing in five revised editions as the widely read Underground Treasures: How and Where to Find Them.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Orton entered Williams College in 1851. He excelled in his studies at Williams, where “…his commitment to science was exhibited by active membership in the Lyceum of Natural History, frequent field trips and nature walks, two summer geological excursions to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, and by serving during his senior year as head of the astronomical observatory.”

Graduating from Williams with honors in 1855, Orton decided, to the disappointment of friends and colleagues, to steer away from his scientific career and to enter the Andover Theological Seminary. Between 1855 and 1866 he dedicated his life to religion and family, graduating from Andover in 1858, and shortly thereafter marrying Ellen Mary Foote. On July 11, 1860, he was ordained pastor of the Congregational church in Greene, New York. In 1861 he headed a church in Thomaston, Maine, where he remained until 1864 when he became the pastor of a church in Brighton, New York.

In 1866 Orton reentered the world of science, when the University of Rochester offered him a temporary appointment, substituting for his former classmate and closest friend, Professor Henry Augustus Ward, who was leaving his post to devote his attention solely to obtaining and supplying natural history specimens to academic institutions and the growing number of American museums. Orton, who had been profoundly affected by the appearance, in 1859, of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species, was happy to return to first love. After reading Darwin’s work, Orton had become engrossed with the idea of evolution through natural selection, believing it to be the correct theory on the development of man, and believing Darwin and his work to be the most important contributions to science and understanding in the recent past. Orton started a correspondence and friendship with Darwin, who encouraged and inspired him to explore South America, which was to be the defining experience of his later life.

In 1867 Orton was selected by the Lyceum of Natural History at Williams to lead an expedition to South America. The expedition was co-funded by Williams and Orton himself, and the Smithsonian Institution donated the scientific instruments needed and arranged to have the specimens returned to the United States. With this project, Orton began a series of detailed journals of his expeditions, most of which display his keen observations of the world around him and his natural talents for the written word. On July 19, 1867, Orton and his group completed the traverse of the Isthmus of Panama, reaching the coastal tropical forest of Guayaquil, Ecuador, about which Orton wrote:

Delight is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who for the first time wanders in a South American forest. The superb banana, the great charm of equatorial vegetation…the slender but graceful bamboo shot heavenward…On the branches of the independent trees sat tufts of parasites…and countless creeping plants, whose long flexible stems entwined snake-like around the trunks, or formed gigantic loops and coils among the limbs…Live and let live is certainly not the maxim taught in these tropical forests, and it is equally clear that selfishness is not wanting among the people. Here, in view of so much competition among organized beings, is the spot to study Darwin’s “Origin of Species.”

This first expedition, in which he crossed South America from west to east, by way of the Quito, the Nabo, and the Amazon, proved to be extremely important, both to Orton and to the scientific community at large. On this expedition, Orton discovered the first fossils ever found in the valley of the Amazon, and his specimens of flora, fauna, fossils, minerals, and anthropological artifacts were proudly displayed in numerous institutions throughout the United States, including the Academy of Natural Sciences, the American Museum of Natural History, the Society of Natural History, the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard, the U.S. National Museum, the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, and the Natural History Museum at Vassar.

He wrote of his journey and findings in The Andes and the Amazon (1870), which, Orton’s biographer, Robert Miller, noted: “…authorities hold to be the best book about South America.” Orton dedicated The Andes and the Amazon to his friend and colleague Charles Darwin: “To Charles Darwin, whose profound researches have thrown so much light upon every department of science…these sketches of the Andes and the Amazon are, by permission, most respectfully Dedicated.”

The Andes and the Amazon; or Across the Continent of South America was the first book to substantively describe and outline the total experience of South America, making Orton, according to Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, “the best authority on the subject of the geology and physical geography of the west coast of South America and the Amazon Valley. No one since the time of Alexander von Humboldt has contributed so much to the exact knowledge of that country.”

In 1869 Orton accepted a professorship at Vassar College, and from 1869 until his death he served as chairman of the department of natural history and curator of its museum. Originally supplied to the college by Henry Augustus Ward, the Natural History Museum, was reinvigorated by Orton’s expertise, soon blossoming into an even more impressive collection of over 10,000 geological and zoological artifacts. While teaching at Vassar and directing its museum, Orton remained an important figure in scientific research and writing; his 1870 book Comparative Zoology, Structure and Systematic was, as Miller writes, “…a leading textbook in the field for a generation…and was printed in thirteen later editions.”

In many ways, Orton was ahead of his time. A fervent advocate of higher education for women, he wrote several articles and edited a book, The Liberal Education of Women: The Demand and the Method: Current Thoughts in America and England (1873), during his first years at Vassar. And at a time in America where believing in evolution, let alone teaching it, was extremely controversial and at times dangerous, Orton proudly and gracefully wrote about and taught Darwin’s concepts of evolution and natural selection—thus making Vassar one of the few colleges in the United States that included evolution in its curriculum.

In the spring of 1873, Orton organized and personally financed his second expedition to South America, this time traveling in the opposite direction from his first expedition. This second journey, which took him up the Amazon from Para to Lima and Lake Titicaca, proved just as important and interesting as the first, and led to the revised edition of The Andes and the Amazon, published in 1876. Upon his return to the United States, Orton immediately returned to his teaching at Vassar and began planning his third expedition to South America.

In 1876 Williams College awarded Orton a doctoral degree, on the basis of his work in South America as well as the research he conducted while teaching at Vassar. In mid-October of 1876, he embarked on his third expedition to South America. Little is known exactly what occurred during this final expedition. What is known is that traveling from Trinidad, twenty miles from the Beni, Orton’s escorts mutinied, taking with them one of the boats and most of the supplies. Attempting to suppress the uprising, Orton was struck on the head and suffered severe hemorrhaging. Knowing that he would not be able to successfully complete his expedition, he began to make his way back home. Orton and what was left of his group paddled 260 miles back up the Mamoré River, where they followed the Yacuma River westward for about 100 miles and then traveled 200 miles by mule to Lake Titicaca. The journey led them through the high Andes where they “…traveled between glaciers which rose a thousand feet on either side of them. Because of the bitter cold, the men dismounted and walked to prevent frostbite; they also suffered from soroche or mountain sickness.”

Finally, on September 24, 1877, they reached the shore of Lake Titicaca. They boarded the schooner Aurora, which took them across the lake on a twenty-four-hour journey to Puno, Peru. Unfortunately, the strain and sickness had been too much for Orton to bear, and he was found dead at daybreak on September 25, 1877, at the age of forty-seven.

Orton’s influence survived his death, particularly back home at Vassar, where his colleagues and former students expressed their admiration for Orton through articles, letters, and speeches. Because Orton was not a Catholic, the government of Puno had refused to allow his body to be laid to rest in their town, but a Spanish newspaper owner, Signor Esteves, who had become friendly with Orton on his various trips to South America and who was an admirer of his work, allowed Orton to be buried on the small Isla de Esteves, located a few miles east of Puno. Forty-four years after his death, the Vassar Alumnae Association raised the money to have a monument erected there in honor of James Orton’s life and career. The New York Evening Post covered the dedication in a lengthy article, which Robert Miller summarizes:

“Fashioned out of New Hampshire granite and designed like the circular tombs of pre-Colombian Indians who inhabited the Titicaca region, [the monument] was erected on Esteves Island in a ceremony attended by the naturalist’s daughter, Anna, and by diplomats and scientists from the United States and South America.”

Orton’s influence as an educator also lived on; his daughters Anna and Susan, both of whom graduated from Vassar, founded a college preparatory academy, which operated from 1890 until 1932, in Pasadena, California. Named The Orton School for Girls in their father’s honor, the school memorialized Orton both as a great scientist and teacher and as an untiring advocate for women’s education. Williams College also honors Orton through the Orton Prize, which is awarded annually to a student who has demonstrated exceptional talent and ability in the field of anthropology.

James Orton possessed an impressive ability to learn and evolve. He was a rare kind of person, forming his beliefs and ideas from the world around him, from the life and beauty that he observed, rather than attempting to force the world into any pre-existing mold. As his Vassar colleagues wrote in November 1877: “He was a scholar in the truest sense of the word, and his labors will always eminently stand forth in the records of scientific exploration…his name will occupy an honorable place in the history of Science and public instruction, his memory will ever be cherished in the hearts of his colleagues, pupils, and friends.”

Related Articles

Sources

Miller, Robert Ryal. “James Orton: A Yankee Naturalist in South America, 1867–1877.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 126, No.1. (Feb. 26, 1982), pp.11-25.

Orton, James. The Andes and the Amazon. New York, 1876.

Orton, James, Biographical File. Vassar Special Collections Library.

Orton, Susan R. “A Sketch of James Orton.” Vassar Quarterly, Feb. 1916.

EMS 2007, CJ 2014, ’15