Undergraduate Life at Vassar College (1898)

“Undergraduate Life at Vassar College,” by Margaret Pollock Sherwood ’86, a professor at Wellesley College, appeared, with illustrations by Orson Lowell, in Scribner’s Magazine in 1898.

The problem, What is to be done with the college woman? has of late been troubling critics and reviewers. Much discussion of the question has perhaps given the public a mistaken idea that she does not know what to do with herself. As a matter of fact, during her undergraduate life and after, she is too busy to be seriously troubled about the uses of her existence, and nobody is less perplexed in regard to her future than she is. In college, the serious undercurrent of work and the bright life, out of doors and in, absorb her. It is only when she is forced into it by pressure from outside that she becomes self-conscious, and stops to wonder if she is a “little queer.” That she is being slowly awakened to a sense of the supposed antagonism between domestic and intellectual pursuits is evinced by a few faint signs, such, for instance, as the debate held not long ago at Vassar on the problem: ‘‘Does a college education unfit men for domestic life?” The question was decided in the affirmative, a result which shows, perhaps, that the college woman is beginning to share the depression of the world at large in regard to this matter, but on the whole she realizes more clearly than does the public that the amount of learning acquired in the average college course in not likely to prove a serious obstacle in any walk in life. It is not the representatives of the so-called “unquiet sex” who place undue emphasis on the college training they receive. For that emphasis, the “eternal masculine” in the world at large is responsible.

The newspaper joke, that leader of thought in American life, has established two widespread convictions: first, that colleges for young men are entirely given over to muscular exercise; second, that life in a woman’s college is a shadowed existence, into which girls are plunged in their youth and freshness, from which they emerge pale, sharp-nosed, spectacled. The fact that both these beliefs are untrue, perhaps lends added charm to them. American daughters go by scores to college, and return active, alert, wakened to keener mental and physical life than they have known before; and American fathers go on grumbling because of a strain that saps the vitality of all girls who study. Of the warmth and light and color of the life in women’s colleges only the initiated know.

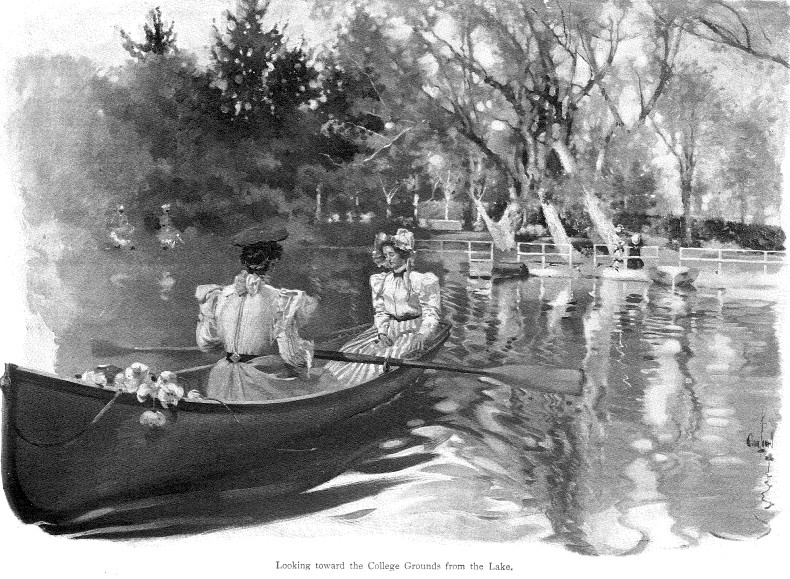

At Vassar, as in many others, the beauty of the surrounding country is a constant call to out-of-door activity. The long tramps, taken just for the love of the deed, or with an ulterior botanical purpose, kindle one’s blood in memory. The walk to Cedar Bridge, where blood-root and anemones come first in the spring; the climb up the long slopes of Richmond Hill to the solitary pine-tree; and the scramble, over burdocks and dead golden-rod, to the top of Sunrise Hill, where one has the blue Catskills to look at on the north, and the bluer Highlands on the south—these are feats for the athletic. For the less ambitious are left the walk round the lake, past the willows: or up the cedar-bordered paths of Sunset Hill, or past the heavy banks of fern in the Glen.

One learns to know much in one’s four years at Vassar—where the mulleins grow on the hill-sides, and to which rocks the columbine comes first in the spring. Certain meadows, guarded by straggling rail fences or broken stone walls, come to be old friends, as do certain beech-trees and hickories and pines. The fading of red and gold color in autumn and the coming of pale green in the spring have peculiar beauty here. There has always been enchantment about the Hudson River valley, and Rip Van Winkle was not the only one possessed by its spell.

The inspiration takes different forms. The college girl is not put to sleep by it, but is roused to physical activity. There is rowing on the lake. Golf has faithful adherents, judging by the number of flags shining against the grass. Basket-ball now occupies the charmed circle bordered by the cedar hedge, and new tennis-courts have been made near the pine walk that borders the grounds. The ’97 Vassarion gives an almost startling result of the athletic training. Field Day, in the spring, is given up to contests. Each class has its basket-ball team. A series of match games leads up to this final one for the championship. Other feats on Field Day are recorded as follows:

Event. Record.

100 yards dash . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11 seconds

220 yards dash . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32 seconds

120 yards hurdle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 seconds

Running high jump . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 feet 5 inches

Running broad jump. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 feet 8 inches

Standing broad jump. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 feet 111/2 inches

Fench-vault . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4 feet 5 inches

The statistics carry one back in thought to those early students in Mr. Lossing’s “Vassar College and its Founder,” pictured in street costume, in flat hats of the “jockey” type, loose sacks, voluminous skirts; or in gymnasium suits, consisting of short skirts with pantalets, loose jackets, and prunella shoes, and one wonders at the evolution of the feminine ideal.

Were those boot-jacks—made after Mr. Vassar’s death, of a tree in his yard, and put into the students’ rooms as souvenirs—a prophecy of this?

The training for the Field-day contests is much promoted by the gymnasium. Here is complicated apparatus—rings for swinging, horses for jumping, chest-weights, clubs—all those devices that an untoward generation has been obliged to make in order to retrieve the physical blunders of its ancestors. The swimming-tank is said not to be in highest favor, because it is not possible for each of the seven hundred young women to have a swimming-tank of her own. That it is used to a certain extent is suggested by the clothes-wringer that guards the entrance. A body of young gymnasts at work training the muscles of the arm, or running to music, is a pleasant sight to see.

In the physical life at Vassar, the river plays a not unimportant part. There were days when it was pleasure bordering on dissipation to take voyages across it in the ferry-boat. Many trips could be taken for one fare. Rowing on the river is not permitted, but there is a vagrant steam-tug that brings one into marvelously near connection with the water, blue in the early afternoon, and touched with gold at sunset-time. The river is associated, too, with more formal pleasures. Sometimes the Junior Party, a courtesy extended to the Seniors by the class below them, took the form of a trip down the river, past the Highlands and Polipell’s Island, almost to New York. The annual pilgrimage to Mohonk leads across the river. This is a long drive, taken when the mountains are brilliant with autumn color. The road leads up, past the yellow and scarlet of maples, and the dull red of oak-leaves and underbrush, to the lake high among the hills, where Quaker hospitality is always waiting.

It is not in out-of-door activity alone that relief from work is found at Vassar. Inside the college doors there is diversion. The social life, apparently very simple, is in reality complex, with subtle distinctions, perhaps more just than the distinctions of the world outside. In the main it is, as all genuine college life must be, democratic. All possible types are represented here. In the adjustment of the diverse aims and peculiarities and the working out of a homogeneous whole lies the interest of college social life. The New England girl is here, with her brains, her family pride, her plentiful lack of this world’s goods; the Western girl, perhaps an heiress, perhaps not; the girl from the Southern plantation, gifted with fire and energy that turn into a high quality of brain-work; the missionary’s daughter from South Africa; the descendant of some old Hudson River family, with a stock of prejudices and convictions to be tried in the crucible of this existence. The maiden who goes arrayed in purple and in fine linen, who fills her room with exquisite carved furniture and rare pottery, lives on the Senior corridor, next the girl who is so poor that on winter nights she is forced to pile her clothing on the bed in order to keep warm. Out of elements like these the college life is made up, with its gayer side, and its side of strict discipline, mental and moral. In spite of coteries and cliques, the true superiority governs, and the aristocracy of the college in an aristocracy of character and brains.

The social life at Vassar is rich in time-honored custom. The most cherished of all in the dancing in room J, after dinner in the short interval before the evening chapel-service. The dancing is more picturesque now than it used to be, the dressing for dinner having grown more elaborate. The half-hour of bright light and music ends in the dancers filing upstairs—a Burne-Jones Golden Stairway to the spectator below—to the chapel. There the sunset color has a way of creeping round to the north windows while the hymns are sung. The two students chosen to be door-keepers in the house of the Lord throw open the folding-doors when the service is over, and the silence is broken by the sound of many voices. The students come out in groups, or two by two, to chatter in the Senior corridor.

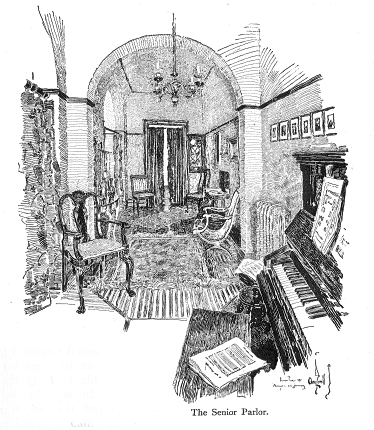

The Senior Parlor

This Senior parlor is one of the distinctive features of Vassar life. One reaches it by passing down a long corridor, whose windows, encircled by ivy, let in the afternoon sun. The room is the centre for the Senior life. For the furnishing the most cherished possessions of the members of the class are contributed—pet rug, claw-footed chair, or curiously carved settle. Sometimes the total effect is one of rare beauty, with the blending colors of stained windows, rugs and draperies, and the quaint shape of choice bits of furniture. The spot has pleasant associations for the daughters of Vassar, with its Sunday-afternoon music, its social gatherings, its quiet afternoons for reading. Universal privileges are accorded the Seniors at Vassar: the Senior vacation, for instance, a time of freedom before Commencement; Senior tables in the centre of the dining room, where the “birthday-girl” always has an ovation; the Senior corridor, and the sacred spot known as the Senior parlor. It all means for the last year closer acquaintance, comradeship of which pleasant memories are afterward carried to the ends of the earth.

Of formal organizations, devoted to pleasure or to profit, there are many at Vassar. The word society suggests a bewildering number of names. A student may, if she wishes to do so, belong to no fewer than thirteen. Philaletheis, the mother of societies at the college, is an old and honorable organization, born December 5, 1865. To this, with its four chapters, Alpha, Beta, Omega, Theta, and its list of non-chapter members, any student may belong. Philaletheis gives, during the year, four hall-plays or farces. Of the other societies, it is necessary only to speak. Their names betray them: The Contemporary Club, a literary organization connected with the English Department, working this year on Russian literature; The Current Topics Club, connected with the department of history; The Shakespeare Club; The Dickens Club; the debating societies, Qui Vive and “T. and M.,“ the latter conducted in the manner of the House of Commons; The ’97 Federal Debating Society; The College Glee Club; Civitas, and The Marshall Club, the former this year devoting itself to a study of the summer—Cuba, the yellow fever, and the Nashville Exposition.

Of societies that have no intellectual or artistic purpose there are several, to wit: eating-clubs, such as The Rabbit and The Nine Nimble Nibblers; social clubs, such as The New England Club, the Southern Club, Daughters of the American Revolution, and Society of the Granddaughters of Vassar, the last made up of children of alumnae. To say that in the debating-societies current topics are discussed with zeal and with logic would be, perhaps, to give unnecessary information. To say that the eating-clubs centre in the chafing-dish, and that the chafing-dish means Sunday-night suppers is perhaps to give desired information. The amount of trouble that girls are willing to bestow upon their small pleasures is cause for standing wonder. Given dormitories not designed for “light house-keeping,” scant supply of domestic utensils, provision-shops, except for the small grocery at the rear of the main building, quite two miles distant, all this suggests difficulty in the way of elaborate repasts. It is but fair to say that the difficulties are nobly surmounted. Paper-knives play the part of the silver in time of need. Scissors can be used in getting olives out of their bottles. With slight informalities like these in serving, goes often great dignity and gravity of conversation. The largest abstract themes can be exhausted at a sitting. The old discussions of “fate, free-will, foreknowledge absolute” are giving way now to debates concerning the future of the working-man but the tone of seriousness remains the same. Hints have been made that these repasts are less primitive than they used to be, that a more sophisticated social life has sprung up round the tea-kettle and the chafing-dish. If this is so, one can but say with Mary Lamb: “I wish the good old times would come again, when we were not so rich.”

Perhaps more interesting than the organized diversion of society-life are the impromptu amusements. Chief among these is the dressing in costume. Certain evenings, Hallowe’en, Washington’s Birthday, St. Valentine’s Day, are always given over to the Ladies of Misrule. Marvellous [sic] creative ability is shown in converting tissue-paper, cheese-cloth, and bits of ribbon into artistic creations. On these occasions outsiders are not admitted. In strict privacy the performers file into the dining-room. There are groups of Salem witches with peaked caps and the brooms, gypsies, minstrels, yellow kids, imps of darkness, ghosts, maidens dressed as bindings of books. Single figures have made themselves famous—Paderewski, irresistible with floating hair, Little Boy Blue, and Maxine Elliott. Hallowe’en is the privileged night for jokes. One year the Sophomores sent the Freshmen a manual of etiquette, based on blunders actually made: “If you wish a pleasanter room, offer to fee the Lady Principal.” “If your laundry-bag is late, take it to the President’s office.”

One year, the Juniors, wishing to satirize the docility of the Senior Class, led a live lamb down the Senior corridor. The Hallowe’en festivities end in a masquerade party.

On Washington’s Birthday the costumes are colonial. Grandmothers’ gowns and ancestral combs are brought forth for the occasion. Girls who take men’s parts wear lace ruffles and queues. Those whose costumes are especially effective, sometimes come in late for dinner, walking slowly for the sake of applause. The dining-room is decorated. After the meal patriotic songs are sung. Last year the holiday on Washington’s Birthday was denied. The students decided to protest. They wore their gala-day gowns to class. On each class-room door was found a poster, setting forth, in terms appropriate to the subject in hand, the cruelty of the Faculty on this occasion.

Interesting costumes are worn at the ice-carnival on the lake, held when the skating is at its best. Of course, it is at night. The lake is lighted by means of bonfires and Chinese lanterns. The costumes are in bright colors, made, perhaps, of red flannel decorated with cotton-batting, suggesting, at a distance, velvet and ermine. There are exhibitions of fancy skating. The entire company moves in procession round the lake, skating to music given by the band.

Sometimes the dressing in costume is used to point a bit of social criticism. Last year the Marlborough-Vanderbilt wedding was given with great éclat. The English guests were finely rendered, especially Queen Victoria, in crown and ermine, more life-like than tongue can tell. Sometimes there is a mock Faculty-meeting, where professors and instructors are represented in costume. Or, perhaps, the dressing-up is done simply to show the costumes of some special locality, as at the Plantation Party, given by the Southern Club on Thanksgiving Night. There was a darkey prayer-meeting, with a sermon on the work required at “Marse James Taylor’s “ plantation. The President [James Monroe Taylor] was one of the guests. As he went out he was followed by calls of “Good-night, Marse James Taylor; good-night Marse James Taylor!”

Another source of unfailing amusement is found in theatricals. Sometimes Shakespeare is attempted, “Twelfth Night” and “The Merchant of Venice” being the most recent. Through her Greek play Vassar made herself famous. The beauty and dignity of Antigone did not suffer even at the hands of the slim maidens who assumed the robes and the beards of Greek men. The ordinary hall-play is not ambitious, recent ones being: “A Russian Honeymoon,” “The Heir at Law,” “The Amazons,” “Americans Abroad,” “A Scrap of Paper,” “Caste,” “She Stoops to Conquer.” There are people who can remember “The Private Secretary” at Vassar, done with great skill and having a convulsing effect.

Perhaps the most interesting theatrical entertainments are the minor farces done for chapter meetings. These rarely meet public attention. One was a dramatization of “Alice in Wonderland” that would have delighted Alice herself. One was a burlesque of an over-heroic play, whose name will not be given. The persecuted lovers were fleeing in a pasteboard boat over the dark-green muslin waves. Crocodiles in horrid scales lay in wait, snapping with large mouths made of rapidly folding and unfolding hands. One of these crocodiles in now a missionary in the Orient; one is an eminent physician.

In the line of drama are the “Trig” ceremonies. The Sophomores in finishing trigonometry always write, for the benefits of the Freshmen, a play in which their recent sufferings are set forth.

A cause of much perplexity in this dramatic activity has been the question of proper costumes for the actors who take men’s parts. Compromise has been effected in the shape of short skirt and coat. That this lends at times an unintentional touch of the comic to a situation intended to be romantic does not always diminish the force of the play. There is apparently protest against this feminine limitation, as is seen in the following list from the ’96 Vassarion:

ADVICE TO PLAYERS

Chairman.—Be not too tame neither, but let the instructions of the English department be your tutor; suit the action to the word, the word to the censorship of the Committee; with this special observance, that you outskirt not the dictate of the Faculty; for anything so overdone is not for the glory of this Society, whose end is to hold, as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature; to show beauty her own feature, manliness his own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure. Now this overdone, or come tardy off, though it make the Freshman laugh, cannot but make the Faculty grieve; the censure of which one must in your allowance o’erweigh a whole theatre of others.

Of other characteristic amusements and customs at Vassar there is a long list. One is the Senior auction, held usually in the Senior corridor. Here the departing class disposes of its superfluous possessions, the proceeds being used to defray the expenses of the class-supper. Under-class girls, in spirit of true hero-worship, vie with one another in securing relics of the departing great ones. The efforts of the auctioneer are often masterpieces. This day is a day of privilege and of license. Even the Faculty may be laughed at, and the Faculty at Vassar can bear a joke at its expense. In 1886 dolls were dressed to personate these dignitaries, and the dignitaries came and purchased themselves in great glee. Professor Mitchell carried away the doll whose modified Quaker costume, gray curls, and common-sense boots represented her own. New devices have sprung up for auction-day. Last year a circus and menagerie amused the bystander.

Growing interest in political matters takes picturesque forms among the girls. At the time of presidential campaigns there are always torchlight processions, long lines of bare heads standing out in relief against the darkness in the flickering light of the torches. Last campaign was an especially thrilling one. Each party had a mass-meeting, to which its prominent members came in costume. Eloquent speeches were made. There was a parade of laboring-men, a parade of Women’s Rights Advocates. Proceedings were as follows:

REPUBLICANS, ATTENTION!

The Arlington Working-men’s McKinley

Sound Money Club,

The New Woman’s Gold Standard Brigade,

The Associated McKINLEYITES of the HAMMER AND ANVIL,

. . . . . . . . .

will call on Mr. McKinley at his home, No 1

Lecture Row, Canton, Ohio, Friday evening,

October 16th, at eight o’clock. All loyal Republicans are invited to be present.

MARCAS A. HANNA,

(per R. C. S)

—From ’97 Vassarion.

SENATOR JONES,

of Arkansas

INVITES ALL TRUE SILVERITES

TO PARTAKE OF

A SUMTUOUS BANQUET IN HONOR OF

THE RT. HON. WM. J. BRYAN,

AND HIS CHARMING WIFE

(to be given at the White House at 8 P.M., Room K).

The menu for the Silverites’ banquet contained, among many others, the following items:

SOUPS.

McKinley in the Soup

MEATS.

Stewed Tariff, å la Protection

VEGETABLES.

Hashed-browned Gold Bugs.

Squashed Republican Hopes.

DESSERTS.

Floating Democracy in a sea of prosperity.

(Gold and Silver) cake.

The processions were most picturesque, the band carrying laboriously its big bass-drum and othr instruments; the Women’s Rights Advocates looking sharp-nosed and thin wearing spectacles and little shawls; the laborers carrying spades, rakes, hods, purloined from the buildings in process of erection, and wearing hats and beards that suggested Bottom of “The Mid-summer Night’s Dream.” The election was carried on with all regularity, the result being as follows:

Republicans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 293

Silverites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Gold Democrats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Prohibitionists . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

The tree-ceremonies at Vassar represent a custom that has all the fascination of mystery. These are held by the Sophomores at the time of the dedication of their class-tree. They meet in secret by night and march with lanterns to the chosen spot, where the solemn rites take place. The Freshmen find out about it all and try to interfere. On this occasion the Sophomores dress in costume. One year they were darkies; one, animals going into the ark; one, vestal virgins in sheets and pillow-cases. After the ceremonies an entertainment is held. On one occasion this consisted of waxworks, representing, with overwhelming effect, various college dignitaries.

The formal social functions must not be forgotten. The two most important are “Phil.” and “Founders,” the names meaning large receptions to which the outside world comes in dress-coat. The dining room is converted into a ball-room on these occasions. The long second-floor corridor is decorated with flowers and with lights, and is furnished with pillows, rugs, and chairs from the students’ parlors. On other occasions, formal courtesies are extended by one class to another. To the Freshmen, as they enter, the Sophomores give a reception, the only form of hazing known here. The Juniors, as has already been stated, give each year the “Junior Party,” the Seniors being the guests of honor. Sometimes this takes the form of a trip down the river, hostesses and guests being for the time possessors of one of the river-steamers, and revelling [sic] in music, banquet, and scenery all at one time. Again, this festivity is a lawn-party, made picturesque by some device—hay-raking, archery, a May-pole dance, or illuminated tableaux.

Commencement time brings various social events. One of these is the class-suppers. This is sometimes held in the Senior corridor, where the iron fire-proof doors are drawn, and the long tables are prepared in strictest privacy. The waiters, listening in solemn appreciation to the toasts and jokes, make a dusky background for the lines of bright heads and bright dresses down the sides of the tables.

At Commencement time come the Class-day ceremonies. These have taken the prettiest possible form in the daisy-chain procession. The long line of white-robed girls, with the heavy daisy-chain passing over their shoulders and hanging in festoons, marches to the eastern side of the main building, where the exercises are held in the afternoon shade.

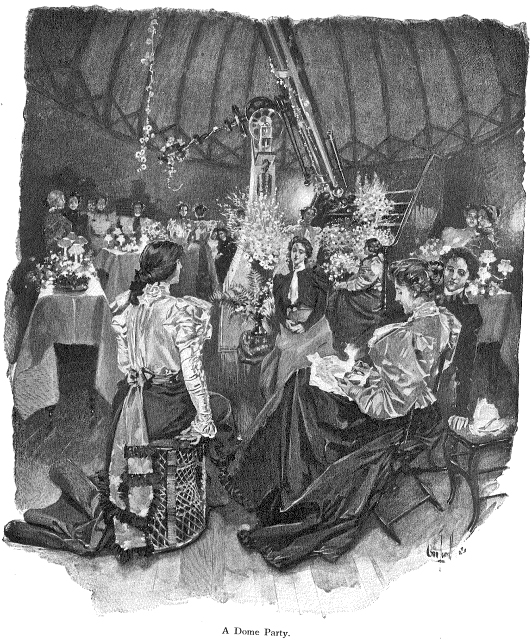

There are many small customs, many quiet corners, and some familiar figures at Vassar that would appeal perhaps to the memory of the alumnae, but would hardly interest the work at large. Students of earlier days recall with pleasure Professor Mitchell at her famous “dome parties.” Only the privileged students of astronomy were permitted to be present. The great lady sat in state among her instruments, her cats helping her receive, for the observatory cat and her kittens were honored members of the household. Rhymes for the dinner-cards were always written by Professor Mitchell herself, and great was her delight when she found it possible to make a rhyming pun upon the name of a guest. Dome parties have been revived in recent years.

Of out-of-the-way corners each student has her favorites. There are the catacombs, white-washed recesses under the main building, reaching out, arch upon arch. They are an excellent retreat for essay-writing. One sits upon a dusty trunk and composes treatises on the will [sic]. There is a cupola, known only to the adventurous few. A broad beam affords a resting-place for one’s self and one’s books. Outside are all the kingdoms of the world and the glory thereof—the Catskills, the Highlands, and the Shawangunk Mountains, beyond the city spires and the river.

There is the Founder’s Room, of which the student may have glimpses if a guest of state is visiting her. Its antique furniture, and its portraits on the walls, wear an air of gracious and old-fashioned stateliness symbolic of that courteous and dignified manner that Vassar has kept through all the rush and hurry of college life.

There is the Art Museum, where the Venus de Milo used to stand with the somewhat unnecessary statement, on a placard at her feet, “Hands off!” Here, too, are the zoological collections, megatherium and ichthyosaurus being cheering company for a rainy day. Less scholarly but more comforting is the small shop at the rear of the main building, where crackers and grapes are dispensed to the hungry, and Smith’s, in Poughkeepsie, a retreat for epicures.

Of familiar figures the most famous is ‘Enery, the gardener, one of the pillars of Vassar. Many anecdotes cluster round his memory. The most famous is his scrubbing with whale-oil the spores from some rare tropical ferns just brought, with great care and trouble, to the botanical conservatory. ‘Enery tells often the story of his walking twenty-five miles in his native England to see, at York, what he calls “a’angin’.” Asked if he considered the effort worth while, he answered reproachfully: “Ee was a friend of mine, Miss.” It was ‘Enery who, when conversing with one of the alumnae, who had lost her husband, looked sympathetically at his auditor and said: “Ah, Miss! Ah, Miss! And so ‘ard to get another!”

There are hints that ‘Enery at times regrets the femininity of his surroundings. As he was working in one of the garden-beds round the circle one day, a tramp accosted him, asking for fifty cents. ‘Enery saw the president of the floral association approaching, and said: “You’d better be off. That’s my boss comin’.” The tramp eyed the slender lady, then turned to go, exclaiming with great contempt: “Well, before I’d have a woman for my boss!” ‘Enery looked shamefacedly after the retreating tramp, and muttered: “Some folks is so ‘igh-minded.”

The Vassar of to-day is like and unlike the older Vassar. Under the present vigorous administration, the college has been roused to keener life. The Hudson River valley is a proverbially drowsy place, and Irving did not discover all its Sleepy Hollows. In the last few years the old story of the wakening of Brunhilde has been re-enacted at Vassar, and the energy of the change shows in all the mental and physical life. A whole new campus has been developed toward the north, and more lights shine through the evergreen hedge. Raymond and Strong Halls have been built; also the gymnasium, the President’s house, the professors’ cottages, Recitation Hall. The new physical vigor shown in the growing interest in athletics is no more marked than the new mental vigor. This is no place to speak of the strong and steady mental training underlying this gayer side of student life just described. The hard brain-work goes on constantly. The college girl is learning how to work harder and to play harder at the same time, losing a little of the old feminine notion that her mental development is in direct proportion to the number of hours she spends over her books. At Vassar the student is winning greater freedom, too, in her domestic life, for the system of self-government throws the responsibility in regard to the order of the community upon the girls. Certain cardinal rules are submitted by the Faculty to the student body. If approved, they are adopted, and the police-force appointed to carry them out is made up of students. The change has brought greater freedom of speech and of action to the students, and the old gulf between the governing body and the populace is being bridged over.

This freedom of speech is evinced by the college publications, the Miscellany, a monthly magazine, and the Senior class-book, the Vassarion. This literary work, with its jokes, its bits of satire, its serious essays, stands half way between the amusements we have just been touching and the life of work which we have left in the background. There is no time to discuss the merits of these organs. They are fair specimens of college-work as one finds it in both men’s and women’s colleges. Good touches are found here and there. Take the following ironic library rules from the ’97 Vassarion:

“1. No student is allowed to use more than six reference-books at a time. She may read one, hold two in her hands and sit on three.”

“2 None of the professors may talk aloud in the library.”

Hints of true pathos creep in the verse in these publications:

“Anglo Saxon.

All are dead that wrote it,

All are dead that read it,

All are dead that learned it,

Blessed death, they earned it!”

’96 Vassarion.

This college life of intellectual stimulus, of hard work, and of play, preserves in the student a kind of freshness, attractive from the merely physical point of view. She is strong and girlish at a time when the society girl begins to fade. She is no blue-stocking, but is alive, interested in people about her, mentally keen, and serious enough to be able to smile at a joke without losing her dignity. Whatever may be the defects of her alma mater, its training, in the study of the laws that govern the outside world, means for her the learning of rule and order and coherence in things. This cannot fail to diminish the capriciousness, the living merely in the moment, of which the sex has so long been accused. Better still than the intellectual training is the companionship in work and in play, that sense of standing shoulder to shoulder with her fellows. Surely this will bring into women’s lives, too long regarded from the merely personal point of view, a certain breadth and largeness.

Sources

Margaret Sherwood, “UNDERGRADUATE LIFE AT Vassar College,” Scribner’s Magazine, Vol. XXIII, No.6, June, 1898

Wellesley College Archives, Library & Technology Services

Related Articles

CJ, 2020