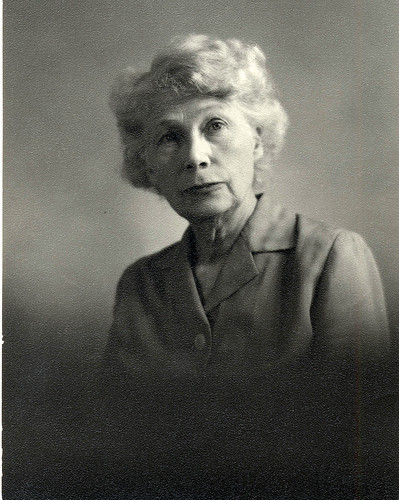

Maud W. Makemson

A complicated series of choices led Maud Makemson to a unique career. Her early focus on writing and on learning languages might have prepared her to be a diplomat rather than a scientist. But early work as a teacher and journalist, in New England, the Southwest, and California led her, eventually, to earth and space science and to renown in astronomy and anthropology. In a long and varied career, she combined her abilities as an astronomer and her early studies in language to become a prolific author and traveler, using her knowledge of astronomy and language, for example, to study the ancient science of the Mayans and Polynesians.

Maud Worcester Makemson was born in Center Harbor, New Hampshire, on September 16, 1891, the daughter of Ira Eugene and Fanny Davisson Worcester. After graduation from the Girls’ Latin School in Boston in 1908, she attended Radcliffe for a year studying Greek and Latin. In her high school and college studies she learned Latin, Greek, French and German, and she studied Spanish, Italian, Japanese, and Chinese during her summer vacations.

After leaving Radcliffe, Makemson took a course in English composition with the New England author and teacher, Dallas Lore Sharp, and briefly taught rural school in Sharon, Connecticut. In 1911, she moved with her family to Pasadena, California, where she met and married Thomas Emmet Makemson and became the mother of three children. Although she separated from her husband—and was divorced from him in 1919—she retained his name.

After her separation Makemson moved to Arizona and took up journalism, working first for the Bisbee Daily Review and then for the Arizona Gazette. During this time she became interested in astronomy, and she began to study it informally after witnessing the great aurora on May 14/15, 1921, which was visible in Arizona. Moving to California that year, she became a teacher, first teaching fourth grade in Riverside, California, and subsequently, having moved again to be near her parents’ ranch, teaching the first four grades in Palmdale. During this time, Makemson resumed her formal education with correspondence courses in trigonometry from the University of California. She also started a correspondence course in astronomy in 1922. In a summer session at the University of California at Los Angeles in 1923, she studied analytic geometry, essay writing, and journalism. A class visit that summer to Mt. Wilson Observatory, above Pasadena, convinced Makemson to apply to the University of California, where she entered as a sophomore the following month. She entered the upper division as an astronomy major in January 1924, was Phoebe Hearst scholar and assistant in astronomy in 1924–1925, and received her bachelor’s degree, Phi Beta Kappa, in 1925.

After graduation, Makemson taught briefly at a rural mountain school near Mt. Shasta and then was an assistant in astronomy and physics at UCLA. After a summer as research assistant at the seismograph station of the University of California at Berkeley, she was appointed research assistant in a survey of minor planets under a grant from the National Research Council in August, 1926. While holding this position for the next three and a half years, she began her graduate studies, taking two graduate courses a semester. At the same time, she taught astronomy and physical geography in Williams Junior College, Berkeley. Summer research at Berkeley’s Lick Observatory in 1927 completed her master’s program, and she was granted the degree in December of that year. She received her PhD from Berkeley in 1930.

Women in science faced almost overwhelming odds in joining the academic ranks at this time. Makemson taught for a year at the University of California (1930–1931), and she taught astronomy and mathematics at Rollins College the following year. She joined Caroline Furness’s department at Vassar in 1932 as assistant professor of astronomy, and she came under consideration for promotion when, after a long illness, Furness died in 1936. President Henry Noble MacCracken, obviously aware that Furness’s successor was, in effect, also the successor of Maria Mitchell and Mary Watson Whitney, sought the advice of Henry Norris Russell, a friend of the college and professor of astronomy at Princeton. The historian Margaret W. Rossiter sees Russell’s response as evidence both of the perceived steep difference between scientific education at men’s and women’s colleges and of his keen judgment in Makemson’s case:

“After speaking at the college and talking with its faculty, Russell wrote MacCracken a long letter in which he described the anomalies of such a research position at a women’s college. Since the position required so much elementary teaching (of the sort his colleagues dubbed pejoratively ‘girls’ college astronomy”), anyone who got an outside offer would tend to leave. Since only men got such opportunities, Vassar should appoint Maud Makemson, already on its staff, as the department’s new chairman and director. Although ‘mature’ at age forty-four, she had done good work, was likely to do more, and would continue to reach the students successfully…. ‘Vassar would not lose prestige’ by her appointment.”

Maud Makemson became the fourth director of the Vassar Observatory in 1936 and full professor in 1944. The author of well over a dozen research articles in scientific journals—several of them while she was still a graduate student—on the orbits of minor planets, comets, and double stars, as well as the early history of astronomy, Makemson had also begun her combination of astronomy with anthropology before becoming the director of the observatory at Vassar. In the summer of 1935, on a Vassar grant, she had gone to Hawaii to study Polynesian astronomy. The result, The Morning Star Rises: An Account of Polynesian Astronomy, was published by Yale University Press in 1941.

While in Hawaii she tackled another astronomical mystery or, as The New York Times for November 17, 1935, put it: “Vassar Professor may Upset Legend….Maud W. Makemson Meets Controversy While on Trip for Astronomical Research.” By local legend, in 1736, on the night the great King Kamehameha I of Hawaii was born, a new and mysterious star, later known as Kokoiki, swept across the heavens. Working from remarkably precise accounts transcribed from unwritten sources and contradicting the legend just as Hawaiians were beginning to plan for the event’s bicentennial, Makemson concluded that the star was Halley’s comet and that it would have been visible from exactly the location noted on December 1, 1758. The Hawaiian Historical Society published Makemson’s “The Legend of Kokoiki and the Birthday of Kamehameha I” in its Annual Report for 1935, but the date of the king’s birth remains unsettled.

At Vassar, Maud Makemson thoroughly engaged her students. She and they computed the orbits of a dozen minor planets, one of which she named “Vassar” and another “Maria Mitchell.” (1) One of her students, Vera C. Rubin ’48—widely recognized as the formulator of the concept of “dark matter”—remembered: “She was a very thorough teacher, demanding high quality work in return. She could be very outspoken if work was not up to her standards. Her interest in the history of astronomy was revealed in the weekly lectures on this subject which were utterly fascinating. Finally, she made a great effort to get to know her students, with a series of gatherings at her apartment throughout the year, at which words games and number games played a prominent role. On one occasion she took a roommate and me to the circus!”

Makemson’s blend of knowledge and accessibility sometimes drew her into controversy. Trial lawyers went to her for critical astronomical information, and the press consulted her about all kinds of celestial phenomena, including flying saucers. Once, during World War Two, Makemson was asked by the press about a rumor that a Vassar meteorologist had predicted 15 clear days of sunny weather. She quickly denied the rumor, warning that it may have been intended to frighten farmers out of planting crops and, if so, that the government should look into it and find the person responsible. She informed the public that, “Forecasts for more than 24 hours are prohibited by the government during the national emergency, and weather maps are not distributed until a week after the date for which they are valid.”

During 1941–1942 Maud Makemson held a Guggenheim fellowship for the study of Mayan astronomy. The Astronomical Tables of the Maya was published in 1943 by the Carnegie Institute of Washington, D.C. Her The Maya Correlation Problem (1946) demonstrated the correlation between the ancient Maya calendar and the Julian and Gregorian calendars .On sabbatical again from Vassar in 1948 she further pursued the subject at the University of Florida and the University of California. The Book of the Jaguar Priest (1951) presented her controversial translation of the sixteenth century Book of Chilam Balam of Tizimin—one of the only surviving records of the Itza people of the Yucatan peninsula— along with discussion of discoveries of Mayan astronomy and mythology .

In 1954, Makemson extended her speculation about the power of primitive astronomy in ancient belief in an article in the Journal of Bible and Religion called, “Astronomy in Primitive Religion.” Telling “a dramatic story of a distant past when religion included the worship of the celestial bodies,” with evidence from China, Mesopotamia, ancient Rome, Greece, and Egypt, Makemson drew on the work of the pioneer French archaeoastronomer Marcel Baudouin in analyzing a map of the stars in Ursa Major and Botes incised on a fossilized sea-urchin amulet from stone-age northern Europe. “The representation,” she asserted, “of Ursa Major…is remarkable for two reasons: first because the relative positions of the stars point to a very great antiquity for the amulet; and second, because the engraver has taken pains to indicate the difference in brightness of the stars, by varying the size of the cavities.” After discussing a variety of star-worship artifacts, including a relatively contemporary account of a star cult reported by the “apostle to the Muslims,” American missionary Sameul Zwemer, she concluded “that in general the various star-cults led ultimately to the seasons of the agricultural year, and to the sun from whose light and warmth all living creatures draw their sustenance.”

A Fulbright teaching fellow in Japan and Punjab during 1953–1954, Makemson retired from Vassar in 1957. Returning to California, she taught astronomy and astrodynamics at UCLA and in 1960 was co-author with Robert M. Baker of Introduction to Astrodynamics. Collaboration with Baker and others led Maud Makemson—teacher, journalist, astronomer, observatory director, and anthropologist—to yet another career, in space research with the Applied Research Laboratories of General Dynamics at Fort Worth, Texas. As a consultant to NASA’s lunar exploration program, Makemson assisted in solving a critical problem for the astronauts. As she put it in “Determination of Selenographic Positions,” published in the international journal, The Moon (1971):

In 1964–1965 when I developed an approximate method for determining selenographic [moon-mapped] latitude and longitude from star altitudes observed from the Moon’s surface, the practical need of such a method seemed most remote. Now in 1970, a method for finding accurate position on the lunar surface is no longer an academic problem, but an essential factor in every selenodetic survey….

The imperceptibly revolving lunar star-sphere provides an ever available reference system, never obscured by atmospheric disturbances or diffused sunlight. The Apollo astronauts, however, reported that as they stood on the Moon’s illuminated surface, the were unable to see the stars, except with some optical aid.

Makemson’s solution to the “academic problem” evolved into a way for astronauts to determine their positions on the moon when they could not use radio or radar. The astronomers could enter the coordinates of three or more stars into a computer, and a program would convert geocentric, or earth-centered coordinates into a selenocentric, or moon-based, map.

Maud W. Makemson died December 25, 1977, in Weatherford Texas. She was survived by her son, Donald Worcester, a professor of history at Texas Christian University, seven grandchildren and 11 great grandchildren. Makemson was a member of the American Astronomical Society, the Association for Advancement of Science (AAS), and the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). She was also a member of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).

Footnotes

- In 1931, Makemson named another minor planet “Radcliffe,” in honor of the Radcliffe Class of 1912, her original college class.

Sources

Maud W. Makemson, “Astronomy in Primitive Religion” Journal of Bible and Religion, Vol. 22, No. 3 (July, 1954)

Maud W. Makemson, The Book of the Jaguar Priest, New York: Henry Schuman, 1951

Maud W. Makemson, “Determination of Selenographic Positions,” The Moon, Vol. 2, Issue 3, (February, 1971)

Maud W. Makemson, “Astronomy in Primitive Religion,” The Journal of Bible and Religion, 22.3 (1954)

Margaret W. Rossiter, Women Scientists in America: Struggles and Strategies to 1940 (Part I), Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984

“Maud W. Makemson, Vassar Professor, Uncovers birth Date of Ancient King” Poughkeepsie “Sun Courier”, November 17, 1935

“Vassar Professor May Upset Legend,” The New York Times, November 17, 1935

“Vassar Denies ‘15 Clear Days.’ Fears Saboteur Started Rumor” Poughkeepsie New Yorker June 4, 1943

“To Locate Yourself on the Moon, Contact Dr. Makemson” Fort Worth Star Telegram, April 15, 1971

Vassar College Special Collections Biographical file on Maud Makemson

Vassar Office of College Relations, “Four Faculty Members Retiring at Vassar” May 19, 1957

CJ, MH 2008