The Experimental Theatre of Vassar College

Perhaps fittingly, what was to be the Vassar drama department emerged from the basement of the Assembly Hall, the former Calisthenium and Riding Academy and the home of the English department. Before a woman who would change it forever arrived from Cambridge, Massachusetts, drama at Vassar had been considered a child of that department, but in 1927 the Vassar College Experimental Theatre was born in the building’s cramped basement.

“There was no green room then—no place for actors to dress and put on makeup and rehearse,” the Miscellany News reported in 1941. “A member of the faculty today remembered Hallie Flanagan ‘rolling up her sleeves and going down into the basement where there were nothing but rocks and reptiles.’”

A native South Dakotan and a graduate of Grinnell College, Flanagan had excelled in “Workshop 47,” George Pierce Baker’s innovative drama course at Radcliffe— one of the few places American thespians could learn playwriting. President Henry Noble MacCracken offered her a job at Vassar even before she completed her master’s degree at Radcliffe. By day the president and a Chaucer scholar and—it soon appeared—by night, a character actor, MacCracken charged Flanagan with enabling student theatre at Vassar. In the challenging decade to come, he supported her aspirations at Vassar, onstage and off.

The inaugural production of the Experimental Theatre, Chekhov’s The Marriage Proposal, took place on the evening of November 12, 1927, in the Assembly Hall. Chekhov was, by the 1920s, a staple of American theatre, and the “experimental” element in Flanagan’s production came not from its text but from its reiterative format. The actors performed Chekhov’s short play three times: first, in a realistic style; next, in an expressionist style; and last, in a constructivist style.

“Chekhov’s play is obviously written to be produced realistically,” wrote Flanagan in a program note. “Yet because of his interest in dramatic experimentation, he would, perhaps, be willing to have his drama illustrate different methods of the eternal theatre.” The Miscellany News declared the experiment “an unusually successful performance,” particularly praising the constructivist adaptation, which “broke down the barrier between actor and audience, and furthermore put a new and interesting aspect on Chekhov’s work by enlisting personal sympathy for the protagonists.”

As a Guggenheim Fellow in 1926, the second year of the program, Flanagan had learned about constructivism from her time in the young Soviet Union, where she met radical Russian theatre-makers like Konstantin Stanislavski and Vsevolod Meyerhold. “I became absorbed by the drama outside the theatre,” she wrote, “the strange, stirring, and glorious drama that is Russia.” Meyerhold believed that “actors must cease to be characters, as in realism, or abstractions, as in expressionism. They must remain actors, using the play as a ball to be tossed now to each other, now to the audience.” The New York Times Magazine wrote that Flanagan’s Chekhov experiment had “made an impression on the great world of the theatre,” while Smith College—inspired by The Marriage Proposal—promptly mounted Twelfth Night in not three but five manners: “Ours at Smith College…was deliberate flattery,” director Samuel Eliot admitted, “though we strove to out-do Vassar at the new game.”

Flanagan swiftly developed a following within Vassar’s gates. The students she taught in Dramatic Production (nicknamed “D.P.s”) became her proud devotees, traveling in packs, sporting blue jeans (often dripping with stage paint), and frequently asking their dormitory guardians for late passes so they could stay in the theater until midnight. Her students unabashedly adored her.

Of course, not everyone approved of Flanagan’s new Experimental Theatre at Vassar. Many in the faculty objected to Flanagan’s visceral interpretation of Shakespeare, particularly in her 1934 production of Antony and Cleopatra where Cleopatra, scantily clad, appeared with a whip in her hand (meaning to lash Antony) but was overcome by his sensual kiss. “At this point,” recalled Flanagan, “one of the members of our audience, a professor of psychology, got up and left, saying audibly that she felt as if she were in a brothel.”

Most notably, however, Dean C. Mildred Thompson stood at odds with Flanagan. Thompson repeatedly rejected Flanagan’s attempts to create a drama department, separate entirely from the English department, where she often found herself stifled by the bureaucracy of a department that did not understand her craft. Vassar, like most of its peer schools, held that to study theatre seriously was to study in a classroom, not on a stage. Flanagan countered the dean’s argument that performing texts was less instructive than reading them, noting in a campus speech in the spring of 1928:

“If a student’s ideas gush forth in a four thousand-word topic on the character of Caliban, we regard it as a legitimate part of the educational process. If, however, his ideas are made visible through the acting of the role of Caliban…we are not sure the process is educational.”

Meanwhile, Flanagan continued to lead collegiate theatre in new and unconventional directions. She not only encouraged her students to perform plays, she urged them to write plays. A 1929 catalogue from the legendary New York theatrical publishing house, Samuel French, included a “Vassar Series,” several of her students’ plays.

In 1933, the Experimental Theatre staged the first American production of a play by the ancient Indian poet Bhasa. His Sanskrit drama, Svapnavasavadatta, or The Dream of Vasavadatta, was thought lost forever until it resurfaced in an Indian library in 1912. In Flanagan’s production, President MacCracken played the role of Udayana, King of the Vatsas. Flanagan the director made no special accommodations for MacCracken the actor. According to the New York Times, “she was severe with Pres. H. N. MacCracken…when he appeared late for rehearsals of ‘The Hippolytus’; he took it like a man, donned a helmet and went on as Theseus.” MacCracken’s daughter Maisry recalled another confrontation in these rehearsals. “When he was rehearsing he would forget his lines in Greek,” she told a student interviewer in 2006, “and he’d turn up his toes in the sandals, trying to remember. Then, Hallie Flanagan would shout, ‘Prexy! Put your toes down!’ This would make him forget his lines again and in trying to remember, the toes would turn up again. Finally, Hallie said, ‘You’ve got to wear shoes to the performance.’”

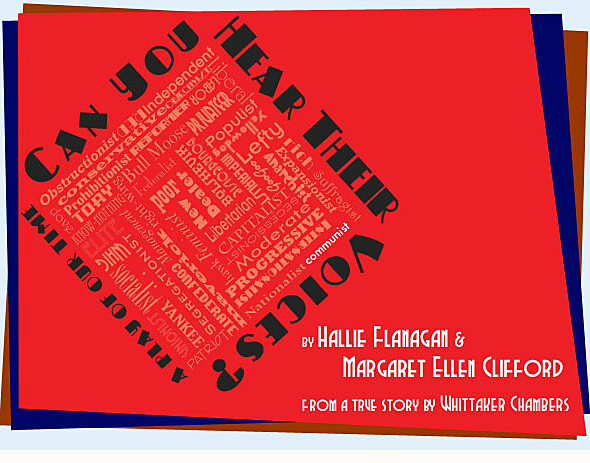

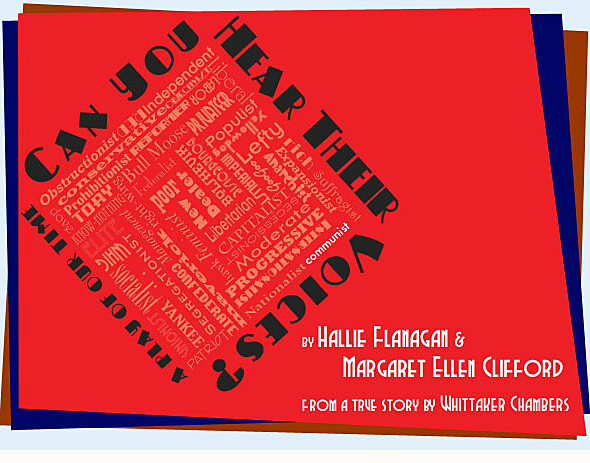

Flanagan’s production of Can You Hear Their Voices? premiered in May 1931, attracting national and, ultimately, international attention. Created by Flanagan and an ex-student, Margaret Ellen Clifford ’29, from a short story by Whitaker Chambers and with material supplied by Vassar students and staff, the play was a proud piece of propaganda. Can You Hear Their Voices? depicted the desperate struggles of Arkansas farmers in the Dust Bowl during the Depression, intercut with scenes set in Washington, DC, showing feeble and ignorant responses to the farmers’ plight. The Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier wrote, “if you have any doubts how effective an out and out propaganda play can be, you may erase them in view of this production.”

The Experimental Theatre’s timely propaganda piece became an international success. Can You Hear Their Voices? was translated into Japanese, Yiddish, German, French, Russian, and Chinese. In 1932 the Japanese Proletarian Theatre League undertook to perform the play before Japanese workers and peasants. The burgeoning Chinese Communist Party also admired the work, but a message addressed to “Comrade Hallie Flanagan” declared that the Party would be unable to perform the play because its non-violent conclusion did not directly advocate the overthrow of Imperialists.

In 1933, Flanagan engaged the Experimental Theatre in a quite different venture, when T. S. Eliot came to Vassar to see the Experimental Theatre’s premier of his verse drama Sweeney Agonistes: Fragments of an Aristophonic Melodrama, as part of the Dramatic Production group’s larger work, Now I Know Love: A Mime Sequence. Despite his initial reservations about letting a college professor mount the debut, Eliot approved of the performance on May 6. “I liked it very, very much. Mrs. Flanagan’s way of presentation was better than my own might have been,” he conceded.

Flanagan’s experience with theatrical propaganda at Vassar served her well later in the 1930s, when she served as national director of the Federal Theatre Project, a $7 million New Deal program meant to put American actors back to work. During the 1937 summer session of the Federal Theatre, housed at Vassar, Flanagan staged One-Third of a Nation, a hard-hitting piece on poverty, rendered in the “Living Newspaper” style that she and the Federal Theatre were pioneering. Referring in its title to a passage in President Roosevelt’s second inaugural address—“I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished”—the piece focused on the slums that surfaced in American cities during the first half of the century. After one summer performance of One-Third of the Nation, the Tenement House Commissioner of New York City, Langdon Post, awed by the power of the evening, said to Flanagan, “This play, performed as it was tonight, can do more to convert people to proper housing than all the shouting I have done in the past three years.”

When Flanagan assumed leadership of the Federal Theatre Project, she recruited her friend John Houseman to teach and to direct Experimental Theatre productions during the 1937–38 academic year. Houseman had impressed Flanagan and critics earlier with The Cradle Will Rock, a leftist musical produced with the Federal Theatre, and he went on to a long, successful career in theatre arts. At Vassar, he taught classes and directed a very well-received staging of John Cocteau’s The Infernal Machine. Looking back, in 1989, Houseman described his year with the Experimental Theatre in modest terms: “If I brought [my students] anything, it was the exciting sense of big-time professional theater which I carried with me from New York as I came roaring onto the campus twice a week and slid to a screeching stop before the Experimental Theater building.”

Despite its successes, the Experimental Theatre contined to be plagued by academic politics. Theatre productions remained under the control of the English department, and tensions escalated between Dean Thompson and Professor Flanagan. Most memorably, their feud played out in the faculty lounge: professors who wandered into the lounge for an afternoon cup of tea “had to decide,” according to Flanagan’s stepdaughter and biographer, Joanne Bentley, “whether to join ‘Hallie’s people’ on one side of the room or ‘the dean’s’ on the other.” While the faculty stood divided between Thompson and Flanagan, the students’ loyalties were clearer. One girl said, “Those who opposed Hallie were green with envy. The dean wasn’t nearly so popular as Hallie.”

Hallie Flanagan also drew the attention of critics outside of Vassar, and many launched attacks far more incendiary than the sort of academic squabbles she was accustomed to. While the New York Times cited Flanagan’s friends as calling her, affectionately, “a soft-spoken slave driver,” less friendly publications pulled no punches. For instance, a 1935 New York Journal editorial vehemently attacked Hallie Flanagan’s past and politics. William Randolph Hearst’s staunchly anti-Roosevelt newspaper asked, rhetorically, of its readers:

“Has she not studied the RUSSIAN drama under the direction of the SOVIET society for cultural relations with foreign countries?

Was she not the honorary recipient of a special ballet performance given for her in LENINGRAD?

And is she not a member of the American advisory committee of the MOSCOW State University?”

Those questions referred to truths about Flanagan’s life. In the next sentence, however, the editorial hurled an unfounded and serious accusation at the drama professor:

“And how happy she must be, BORING FROM WITHIN, dragging her university, despite its respectable name, deeper and deeper into the mire of Communist propaganda and disloyalty to America.”

But Vassar—the students, at least—would not stand idly by as right-wing media vilified their beloved, renegade teacher. The staff of the Miscellany News reprinted the Hearst editorial in their October 30, 1935 issue, complete with the board’s own editorial, a fierce rebuttal entitled “Patriotism—From Bad to Hearst.” The piece acknowledged that Vassar students could laugh away the charge that Hallie Flanagan was “dragging” the college down, but they could do little about the opinions of the New York Journal’s five million readers.

The United States Congress, displeased with Flanagan’s politics, defunded her Federal Theatre Project in 1939, and she found herself doubly insulted when Dean Thompson, a couple of months later, decided to finally approve drama as an independent department and major. Flanagan had been fighting for this change, and only when Flanagan was away from Vassar did the dean endorse the idea. Having married Vassar Professor of Greek Philip Davis in 1934, she returned to Poughkeepsie. After Phil Davis’s death in 1940, she took a three-year leave of absence to serve as acting dean at Smith College. In 1945, she announced her decision to stay at Smith.

“Hallie’s pioneer period at Vassar was of relatively short duration,” remembered one former D.P., “but so dense that I picture her sleeping in a full suit of armor, with sword and dagger by her side, ready to slay the next dragon.” Flanagan, it seems, would have admired that description; as she observed after hearing a run-through of The Cradle Will Rock, “It took no wizardry to see that this was not a play set to music, but a music-plus-play equaling something new and better than both….The theatre, when it’s good, is always dangerous.”

Flanagan left Vassar, but her Experimental Theatre remained a permanent fixture, especially under the auspices of the new drama department, chaired by Winifred Smith ’04, a former English professor. When, in 1956, Professor Emeritus of Drama Evert Sprinchorn began teaching at Vassar, Smith’s and Flanagan’s Experimental Theatre was in full swing. “The new approach was to balance practical theatre with the literal study of theatre,” he recalled. “The idea was 50/50. So even in the introductory course, we taught students about the history of drama, something about play reading, but we also required the students to be involved in a production. And that continued for all four years. You took courses in dramatic literature, and also courses in production. It was an almost perfect 50/50 balance, which I thought was remarkable.” Sprinchorn’s reference was to Drama 220, which Winifred Smith began teaching in 1940. The class sought to “cover the whole history of drama, from the Greeks to the present time, in four semesters,” explained Sprinchorn. “And every drama major had to take those four semesters.” Drama 220, later a two-semester course called “Sources of World Drama,” remained a required course for Vassar drama majors. In terms of production, however, the number of plays performed each year changed dramatically. In the days of Hallie Flanagan, and her successors, Winifred Smith and Mary Virginia Heinlein ‘25, the Experimental Theatre gave several shows each annually—sometimes over a dozen in one academic year.

In 1933, Flanagan declared that the department’s production, whatever their number, would always be diverse. She explained, “this means that each cycle of undergraduates may have seen in the Experimental Theatre, four historic dramas, four bills of writing by their own college contemporaries, four experiments in new methods of stage craft, and four plays concerned with modern problems.” Mary Virginia Heinlein, during her time as director of the Experimental Theatre (1942–1961) enjoyed less popularity than her legendary predecessor; she was strict with students, expecting them to appear for class unless they stood “at Death’s door.” Nonetheless, she delighted Vassar audiences in the 1940s and 50s with an eclectic array of performances. Some highlights included Eugene Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano (1958); the American premieres of William Saroyan’s Elmer and Lily (1943) and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Les Mouches (1947); Ibsen’s Peer Gynt (1945), e.e. cummings’s him (1944) and Lorca’s Blood Wedding (1945), along with several plays written by students.

After Heinlein’s death in 1961, her colleague Norris Houghton took over as leader of the Experimental Theatre, and aimed to focus the drama department’s energy toward producing fewer plays each season. Under Heinlein, the department sponsored, at one time, fourteen productions in a year. In addition, Houghton thought students needed more exposure to the theatre profession outside of the classroom, and outside of Vassar. He denied claims that he was trying to “professionalize” a department in a liberal arts institution, but, in some ways, he did just that. Among the many working theatre artists who visited Vassar were: well-known actors such as Anne Revere and Mildred Dunnock; the comedian Dorothy Sands; the dialect coach Elizabeth Smith; directors Joseph Anthony and Milton Katselas; and the well-known dancer and choreographer Janet Reed. Houghton sought to modernize the Experimental Theatre’s technology, but was discouraged when his calls for a new theatre building went unanswered. In 1967 he left Vassar to start the Conservatory of Theatre Arts at SUNY Purchase, a campus opened in that year and devoted largely to the arts.

As of 2015, in its 88th year, the Experimental Theatre, now housed in better accommodations than Avery’s rock-and-reptile-riddled basement—the Hallie Flanagan Davis Powerhouse Theatre (1973) and the Vogelstein Center for Drama and Film (2003) with spaces and facilities students in the 1930s and 40s could only dream of—still remains a vibrant fixture at the college. Yet it is not the same as it once was. Norris Houghton expressed the frustrations of those many successors who joined the ranks of the Experimental Theatre over the years:

“I seemed unable to restore to Vassar’s Experimental Theatre the excitement of the twenties and early thirties, when its inspired founding director, Hallie Flanagan, was at the helm. Since that time it had never truly justified the word ‘experimental.’ Were the times that different? Were the 1920s and ‘30s more open to artistic experiment than the early ‘60s…? Perhaps a new definition of ‘experimental’ was needed for a new generation, but if so I never discovered it.”

Related Articles

- Hallie Flanagan Davis

- Mary Virginia Heinlein

- John Houseman

- Norris Houghton

- Henry Noble MacCracken

- Calisthenium and Riding Academy

Sources

Joanne Bentley, Hallie Flanagan: A Life in the American Theatre, Knopf, New York, 1988

Hallie Flanagan, Arena, Duell Sloan and Pearce, New York, 1940

Dynamo, Duell Sloan and Pearce, New York, 1943

Shifting Scenes of the Modern European Theatre, Coward-McCann, New York, 1928

Ellen Brent Senay Jones, “Hallie Flanagan and the Vassar Experimental Theatre,” [Master’s thesis, Tulane University, 1964

Helen Riesenfeld, “Theatre Tries Experimentation,” Miscellany News, Vol. XII, No. 14, Nov. 16, 1927

“’Now I Know Love,’ is Experimental Theatre Finals,” Miscellany News, Vol. XVII, No. 44, May 3, 1933

“U.S. Dollars for Pink Plays: $3,000,000 Worth of Stage Boondoggling,” New York Journal American, Oct. 24, 1935, reprinted in the Miscellany News, Vol. XX, No. 47, Oct. 30, 1935

“Patriotism—From Bad to Hearst,” the Miscellany News, Vol. XX, No. 47, Oct. 30, 1935

Everett Sprinchorn,“Stagestruck in Academe,” Vassar Quarterly, Spring 1991

“Interview with Evert Sprinchorn,” Vassar Online Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/interviews-reflections/evert-sprinchorn.html

“Mary Virginia Heinlein,” Vassar Online Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/faculty/prominent-faculty/mary-virginia-heinlein.html.

Norris Houghton,” Vassar Online Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/faculty/prominent-faculty/norris-houghton.html

“John Houseman,” Vassar Online Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/faculty/prominent-faculty/john-houseman.html

Much of the earlier content in this article, on Hallie Flanagan especially, comes from an unpublished paper by Patrick Brady, “A Dangerous Drama: Vassar, Hallie Flanagan, and the 1937 Federal Summer Theatre,” written in 2011 for James H. Merrell’s History 160 course at Vassar College.

PB, 2015