Dance at Vassar

“Among other physical exercises claiming consideration, dancing has been presented to our Executive Committee for their considerations and has been urged by many citizens. The attention of the Christian community has been awakened by recent writings pro and con on these questions. The latest…on the ‘Incompatibility of Amusements with Christian Life.’…Years ago I made up my judgement on these great questions in the religious point of view and came to a decision favorable to amusements. I never practiced public dancing in my life and yet in view of its being a healthful and graceful exercise, I heartily approved it and now recommend it being taught in the college.”

Matthew Vassar

The founders of Vassar College maintained that a young woman should have “a sound mind in a sound body,” and from its inception they emphasized the necessity of female physical fitness. James Renwick’s design for Vassar’s Main Building acknowledged this emphasis, along with the opinion of the time that Vassar’s young women would need to feel a sense of community to succeed academically. Thus, the residential rooms had windows facing into the main hallway, which was twelve feet wide. The intention was that the interior windows and wide hallways would make a stroll through the main corridor feel like a stroll through a town’s streets and would encourage the young female students to be social and active. The halls would enable them to join in exercise throughout the winter months. After the college’s opening these halls evolved to another purpose: dance. Despite Lady Principal Hannah Lyman’s complaints that dancing did not comply with Christian principles, recreational dancing occurred in Main’s “J Parlor” and in its main corridor.

In 1866 fitness appeared elsewhere when Vassar opened its first gymnasium, the Calisthenium and Riding Academy. In pursuit of what the 1865 prospectus declared would be a “vigorous physical education program,” Delia Williams, the physical education instructor, required students to attend physical education classes at least three times a week. These classes were the beginning of dance courses at Vassar and consisted of aesthetic dancing to music and Swedish Calisthenics which was considered, according to the its advocate, Dr. Dio Lewis, “training to develop the beauty of the human figure, and to promote elegant and graceful movement.”

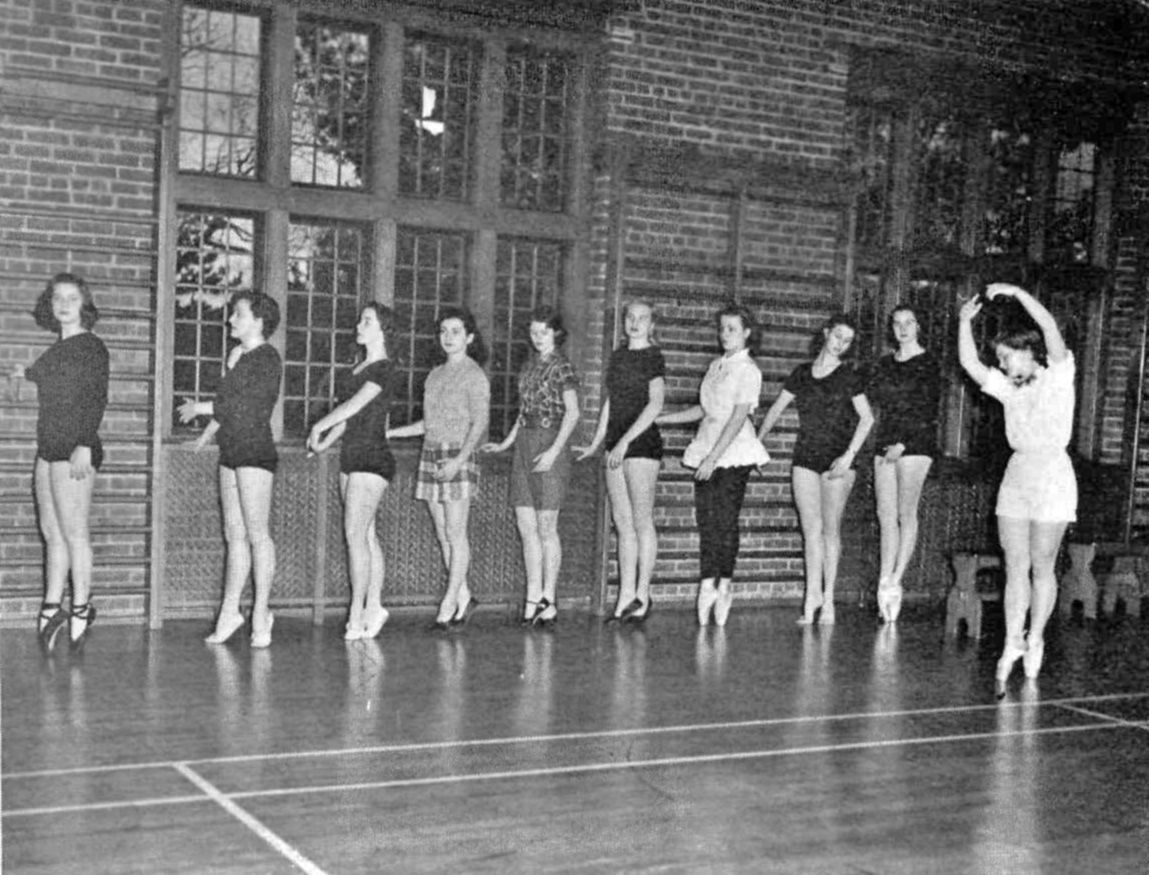

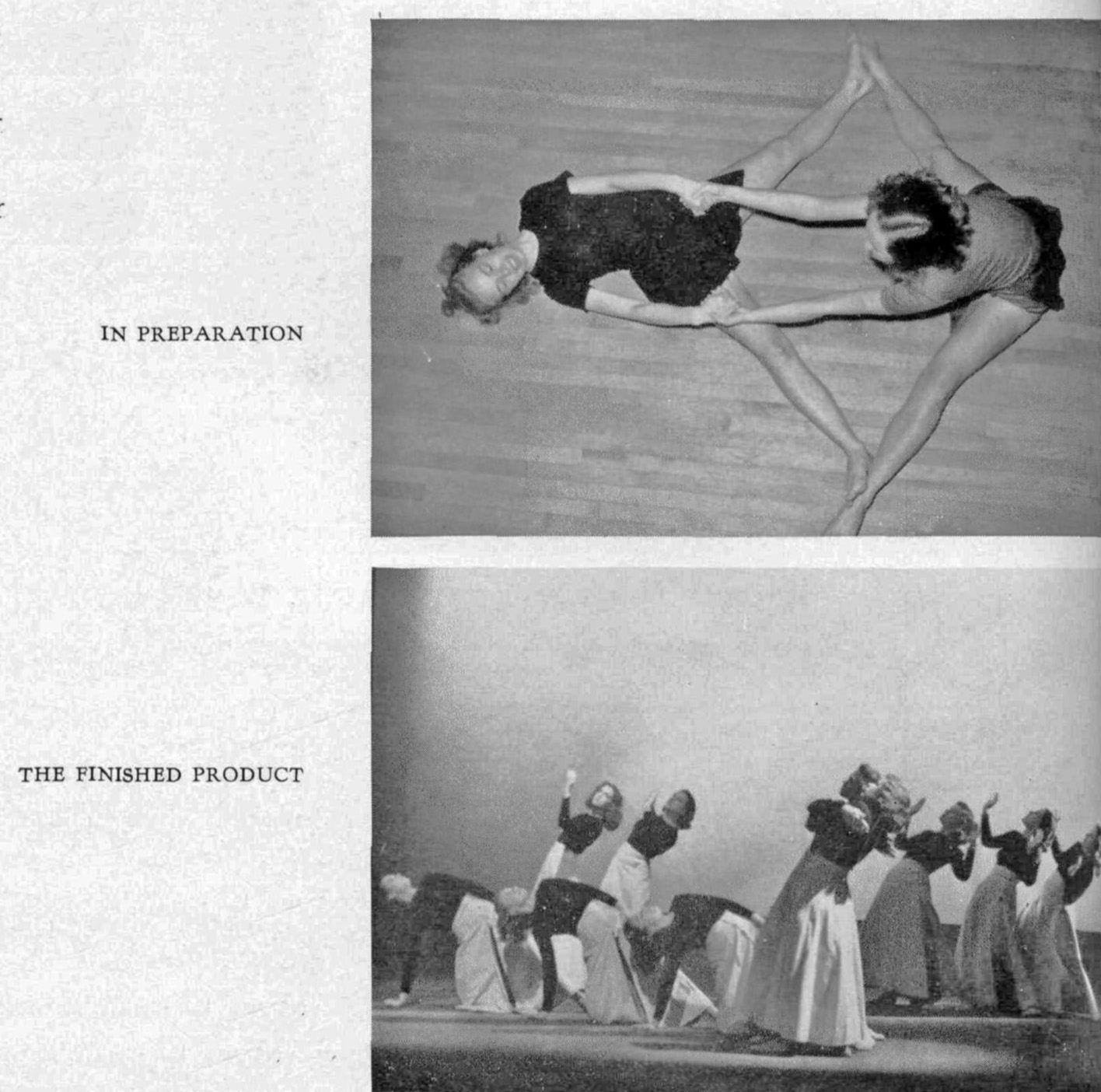

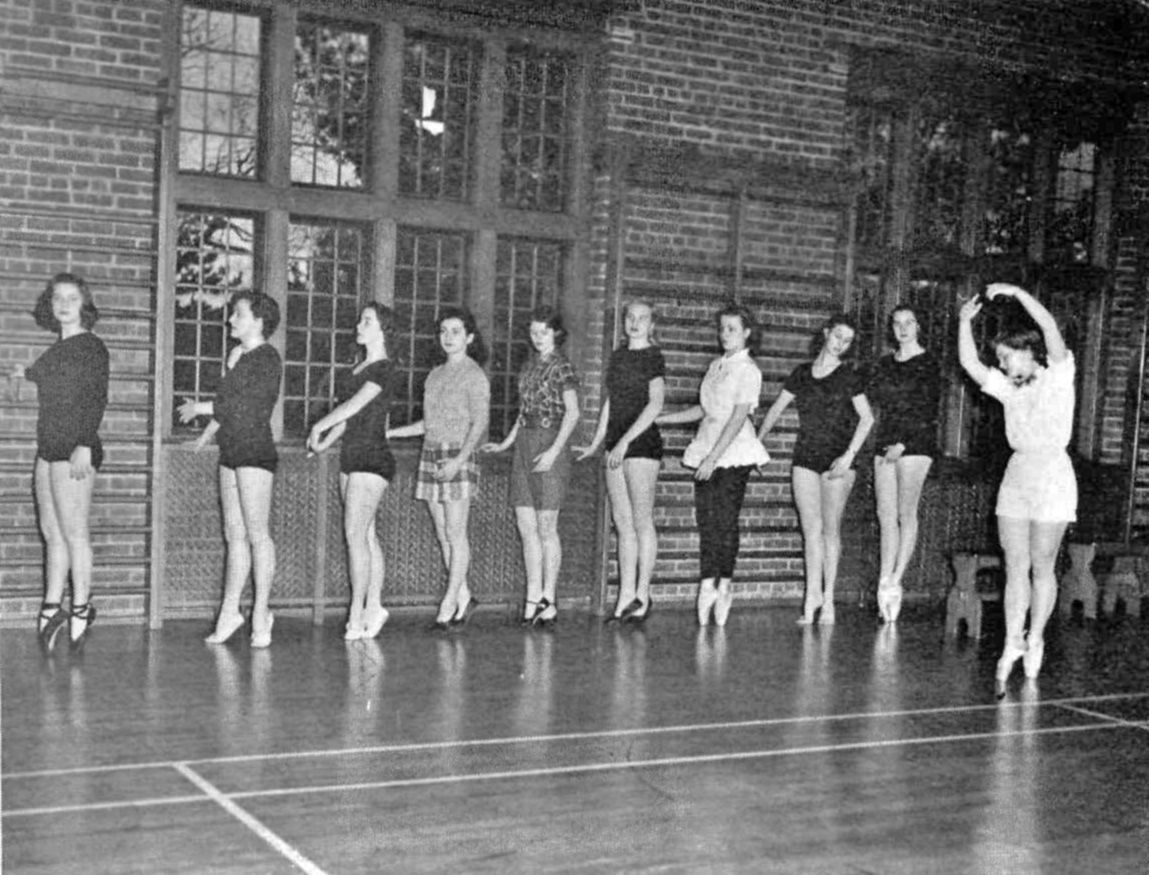

Because of the original emphasis on physicality and dance as a form of fitness, it was not until 1898 that the college offered its first academic dance course, thus recognizing dance as both exercise and art form and allowing students the opportunity to invest creatively in their exercise. By the early 1940s, some formal dance training was available to students, and modest production of dance programs became a part of the academic year.

The Vassarion began to record this gradual progress. “The peak of Vassar’s dancing,” 1941’s yearbook proclaimed, “is the dance group recital with its beauty of line and ingenuity of creation. Unless you are an intimate friend of a dance grouper, you are apt to get a shock when you recognize some lovely, slim, young thing, sprinting gracefully across the state of Students,’ as that lank-haired individual who sits near you in class.” And over a decade later, although the group’s work was still an extra-curricular commitment, a photograph shows the beginning of more demanding and classical formal dance training.

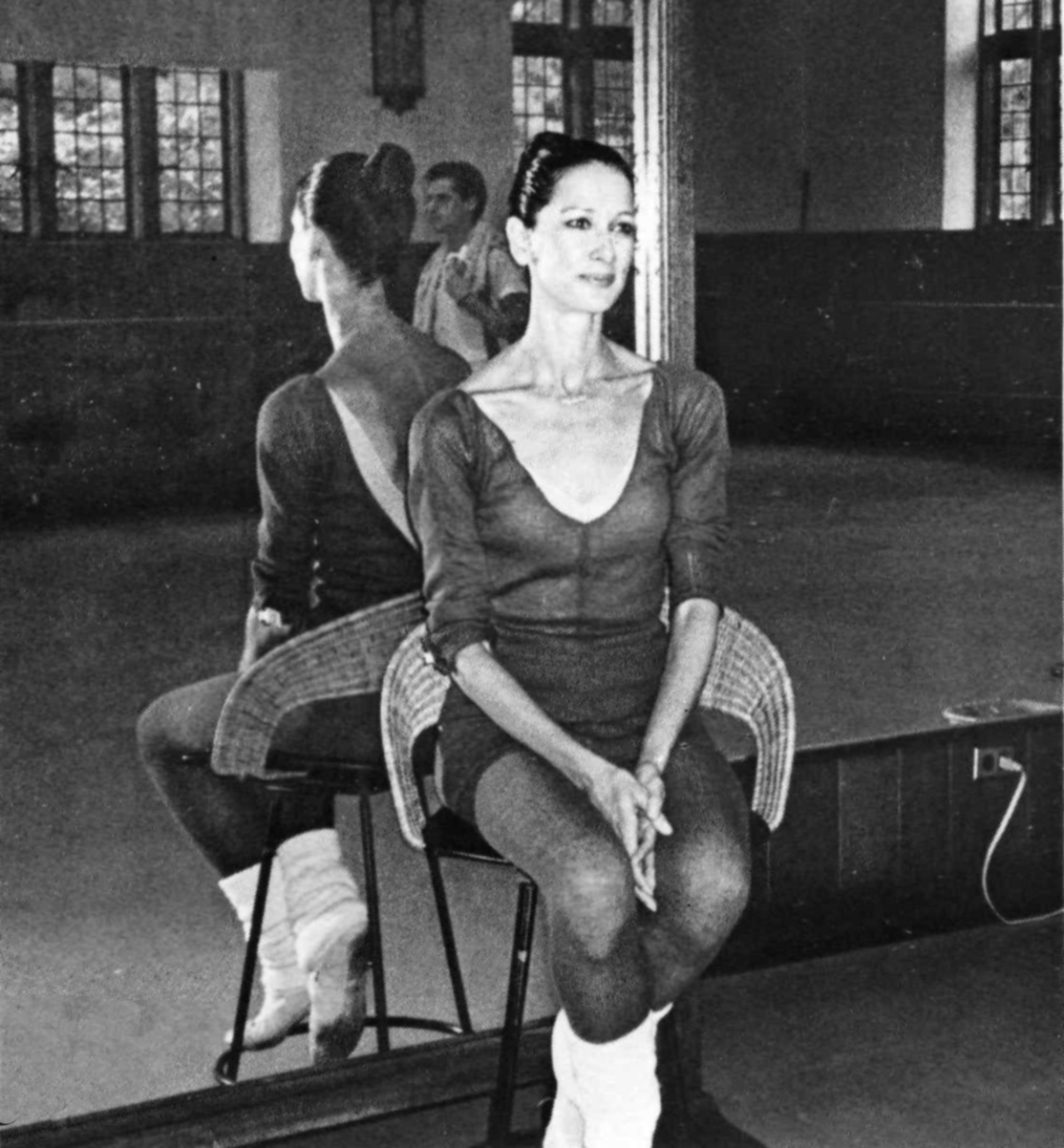

In the 1970s, Sherrie Barr, assistant professor of physical education, extended the opportunity for students to be creative in dance through the establishment of the Vassar Dance Theater. The dance theatre gave those students who auditioned and were accepted opportunities to choreograph and perform original works. But dance remained a small presence within the physical education department until the arrival of a former dancer with the Radio City Music Hall Ballet and the New York City Ballet’s educational division, Jeanne Periolat, at Vassar in January 1975. Periolat’s advent marked the beginning of the recognition of dance at Vassar as an independent, serious educational discipline. Initially hired as a part-time ballet teacher for one semester, she initially registered 65 students and placed the rest on a waitlist. Students seeking to join her non-credit classes were numerous—and vocal— and her appointment was almost immediately extended.

Despite this overwhelming interest in dance, Periolat says that “Vassar was very naive in terms of serious dance. What Vassar needed was information about good dance and how to create it.” Before Periolat, training in ballet— the fundamental technique of most forms of serious dance—was nonexistent at Vassar. She gave the college its first taste of what good dance was and could be, setting off a dance boom that propelled the growth of dance at Vassar.

In 1977, Elizabeth Wynne (’79), a Vassar student inspired by Periolat, urged a dramatic change in the way ballet was taught at Vassar, circulating a petition calling for academic credit for ballet. At the time ballet classes were considered elective exercise classes for which students had to pay an extra $38-$63. Modern dance was already being offered as an academic course for credit, and Wynne did not understand why ballet classes with Periolat were not. The continued demonstration of high interest in the dance classes around the time of class registration caused the student body to come together and fight for this change. Wynn’s petition was signed by 1,174 students, resulting in ballet being added to the curriculum and Periolat being hired as a full-time instructor. This, however, did not ease the burden placed on Periolat and Barr to meet the demand and expectations of the students. The chairman of the physical education department, for example, allotted only $500 annually for guest lecturers for dance, so when Periolat invited renowned ballet dancer Edward Villella to teach a master class, each student in her class had to contribute $7 to fund his visit.

Periolat thought that dance was constrained by its location within physical education,—that it missed opportunities both for the study of the history of dance and for performance. A performance aspect, she believed, was integral to the study of dance, moving it beyond the academic study of technique to present the art form as a whole. At the time, only the most advanced students had the opportunity to perform with the Poughkeepsie Ballet Theater.

In the fall of 1979, and again in May 1980, Periolat proposed the separation of dance from physical education. This proposal was, she said, “initiated by physical education department members and reflects the department’s unanimous views on the subject.” Despite her efforts and resounding support from faculty and students, the proposal was not accepted on the grounds that the college was avoiding the proliferation of small departments.

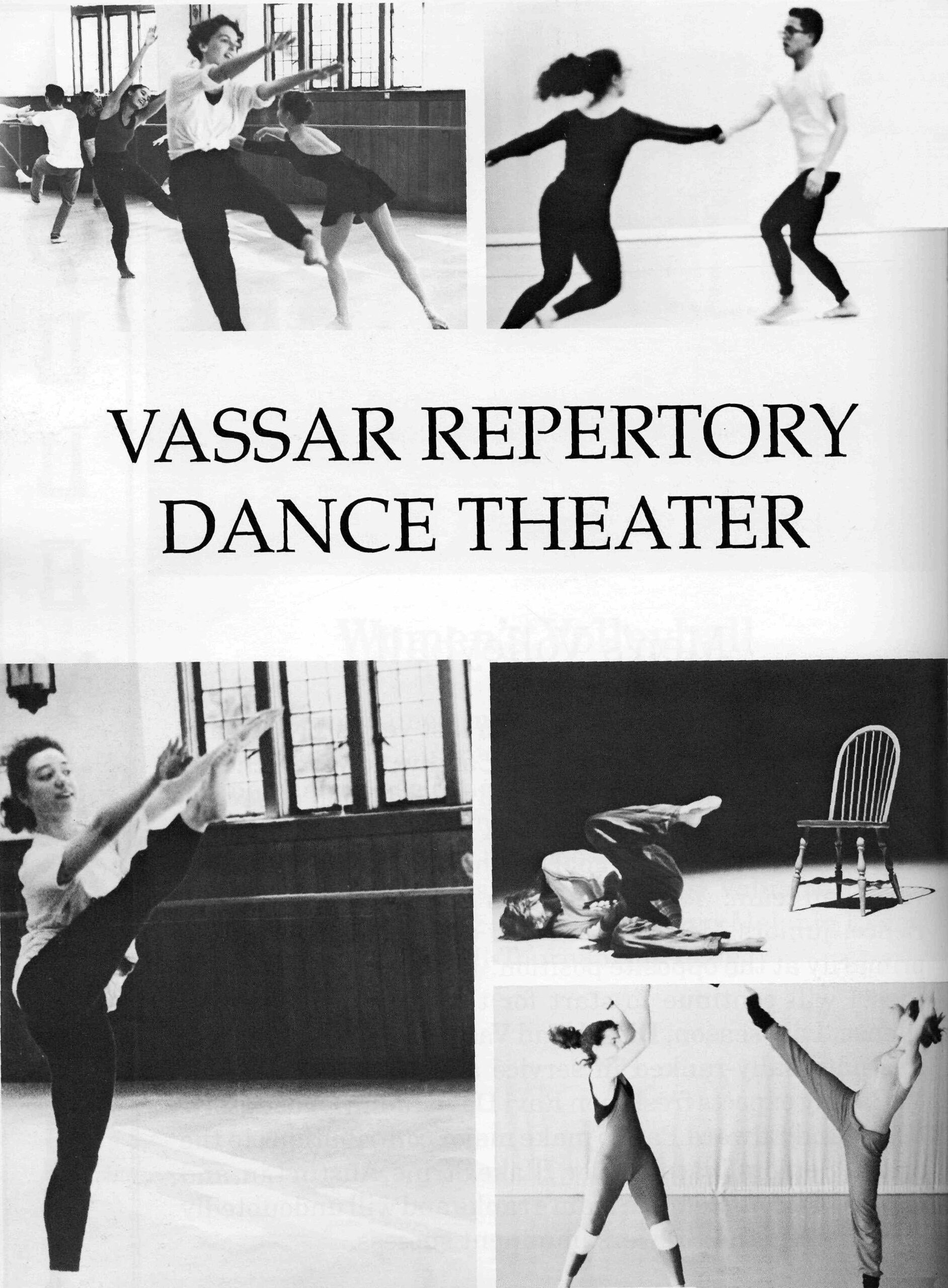

In April 1980, with over 68 people waitlisted for next semester’s beginning ballet class—thus demonstrating the consistently high interest in dance and the need for an extended dance faculty—students began another petition. This time the goal was hiring another dance teacher. In the fall, Ray Cook, a trained ballet and modern dancer known for his work in the form of dance notation known as Labanonation, joined the dance faculty. Cook was hired because of his ability to interpret and teach repertoire through Labanotation, a skill that not many had. He also wanted to teach students modern dance repertory, and thus the Repertory Dance Theater (RDT) was created. There had been no formal company and very few, if any, male dancers. To join the Repertory Dance Theatre, students participated in an annual audition that was open to the entire student body. Auditioned students were then voted on by the current troupe. Dance was still also not even listed in the school catalogue, a fact Cook quickly changed.

Under the guidance off Periolat and Cook, the company became more solid and professional. For the Repertory Dance Theater’s first performance, in its ground floor studio in Kenyon Hall, the audience, consisting of a few friends and faculty, sat on the floor. During All Parents’ weekend of 1982 The Repertory Dance Theater gave their second performance, on a rainy day, and yet visiting parents stood outside the packed studio in order to get a glimpse of the dancers. “This is when I thought we must be doing something right,” Cook recalled. That spring, The department of physical education became the department of physical education and dance.

In 1982, the dance faculty occupied the entire south wing of Kenyon Hall, and all the studio spaces there were devoted to the study of dance. But all wasn’t well. Previously, costumes and sets had been stored in the old Kenyon swimming pool, left empty by the erection in 1982 of Walker Field House. Every once in a while, however, costumes disappeared. Students had figured out how to access the pool from a back door and were taking costumes for their own entertainment. On another occasion, the dance office learned of plans to put academic classrooms in the former men’s dressing room, which the Repertory Dance Theater used for rehearsals. Defending their space, supporters of dance posted blackboards in the room stating that it was the location for the Repertory Dance Theater’s weekly meetings. Although this allowed the company to retain the space for a few more years, Cook continuously searched the campus for an appropriate studio and performance space.

The music students had Skinner Hall and the theater students had multiple venues on campus, the dancers struggled to break onto the stage, so in 1983 Cook and Periolat took their search off campus, turning to the historic Bardavon Theater in Poughkeepsie. Originally, in 1869, an opera house, the building had been renovated as a performing arts center, suitable for dance. With no training in lighting or sound, Cook quickly put a performance together, going to students’ rooms to edit taped music for their choreography. The tape barely fit onto the reel, causing difficulties throughout the performance. Despite other successes, attendance to RDT’s performances was still meager. According to Cook and Periolat, only about 150 people attended the Bardavon Gala that year, even when tickets only cost a dollar. Hoping to gain more recognition outside of the campus, the group changed its name to Vassar Repertory Dance Theatre, quickly called across campus VRDT. Soon, men began to join the company. At first, many parents were dubious about their sons’ dancing on a stage, but Cook was very careful to ask the students to do only what they could perform comfortably.

Over the next few years, Cook encouraged his dancers to sell 30 tickets each and to bring a companion to the Bardavon on each arm. It took about five years to fill the Bardavon, but in a few years things changed: dancers were now lucky to even have 30 tickets to sell to their friends and family, the demand being so high that by 1989, Periolat had to turn people away from the Bardavon because the shows were sold out.

Thanks to the new company and its arrangements, students were performing dance for credit (one unit for the year) for the first time in Vassar’s history. VRDT gave creative students the chance to try out their own choreography on a cast of their choosing, learning how to stage their works in the process. The company required dancers to elect an additional two courses in dance in order to maintain their technique, and any more than three absences from these classes, resulted in their dismissal from the company. By learning professional repertory, students were also studying the history of dance. This gave them a context in which to ground their pieces with a deeper understanding. Works by George Balanchine and Doris Humphrey were staple components of VRDT performances throughout the 80’s and 90’s, evidence of the high level of dedication with which the company approached the study of dance.

Over the years many renowned dancers have come to lecture and teach at Vassar. Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Mark Morris, and Twyla Tharp have shared their knowledge and inspired the students to try new methods of movement and performance. Their presence at Vassar suggests the dance faculty’s passion for and dedication to their art despite the lack of a independent departmental status. “The downstairs studio was always a dance studio,” said Periolat. “From the time Kenyon was built (1934), we know that there were women working in that room, serious about dance.”

Periolat continued to advocate for the separation of the dance department from the department of physical education. Her husband, Roman Czula, by then the chair of the physical education department, stayed out of the way of her efforts for an autonomous dance department; in return, Periolat admits, she agreed not to vote against the hiring of the new soccer coach. In 2005, during a period of departmental transition, Periolat again submitted a proposal to create a separate department of dance. This time the proposal was approved, and Vassar’s department of dance was finally realized. She became the de facto chair of the new department. Periolat says that there was no point in trying to create a dance major because of the small size of the department. There simply were not enough faculty members (usually three or four) to provide such courses as advanced dance history and kinesiology, which would be necessary for a major.

In 2006 Kenyon Hall was renovated for dance and during construction, the studios were temporarily located on the south side of the campus in the New Hackensack Building, which was hastily furnished with wood floors and mirrored walls. With the completion of renovations, the dance department had access to a new dance theater built in the shell of the old swimming pool. Named after the college’s ninth president and the theater’s advocate, Frances Daly Fergusson, the dance theater seats 236 and is equipped with professional lighting, an adjoining green room and dressing rooms as well as storage space for costumes and props.

Interest in dance has remained steady since its rise in popularity in the 1970s. The department offers non-major elective courses, allowing experienced dancers to continue high levels of training and complete beginners to approach the art for the first time. Courses in jazz, ballet and modern dance are offered, as well as a repertory course in the works of Martha Graham, taught by Stephen Rooks, a former principal in her company. VRDT is now under the direction of John Meehan, former director of the Hong Kong Ballet. VRDT continues to promote high levels of training and dance study, providing opportunities for students to create pieces for the annual performances in the dance theater and for the spring semester’s Bardavon Gala.

Many people are surprised that Vassar does not offer a degree in dance. However, if one were to ask a dancer about this arrangement, he or she would respond that they are in the dance department because they love to dance, not because they are competing for a future contract. “Everybody can figure out how [to dance], if they care about their bodies,” said Jeanne Periolat, discussing the development of dance on Vassar’s campus. Dance at Vassar has evolved into a modern and dynamic art form that changes each year, encouraging individual students to explore their interests and style of movement under the instruction of experienced professors.

Related articles

Sources

“Not a Dancer’s Delight,” Miscellany News, vol. LXVI, no.11, April 22, 1977.

“Dance: For the Sake of Art,” Miscellany News, vol. LXVIII, no.21, November 2,1979.

“Students Petition Administration for Third Dance Instructor,” Miscellany News, vol. LXIX, no.10, April 18, 1980

“New Dance Instructor Possible,” Miscellany News, vol. LXX, no.10, November 21, 1980.

“Credit Due for Dance,” Miscellany News, vol. LXX, no 12, December 5, 1980.

“The Dance Program at Vassar,” Miscellany News, vol. LXXIX, no. 1, September 1, 1982.

“Dance Theatre Limbers Up,” Miscellany News, vol. LXXIV, no. 3, September 28, 1984.

“Dance on the Move,” Miscellany News, vol. LXXXI, no. 3, June 1, 1985.

“Dance at Vassar,” Miscellany News, vol. LIII, no. 5, June 1, 1986.

“Dance Rep Opens at Bardavon,” Miscellany News, vol. LXXVII, no.16, March 6, 1987.

“Repertory Dancers Uplift in First Workshop,” Miscellany News, vol. LXXVIII, no. 7, October 30, 1987.

Vassar College Special Collections, Subject File 25.63, “V.C. Dance Theatre.”

Interview with Jeanne Periolat Czula

Interview with Ray Cook

HK, 2017