Swift Hall

Swift Hall (1900)

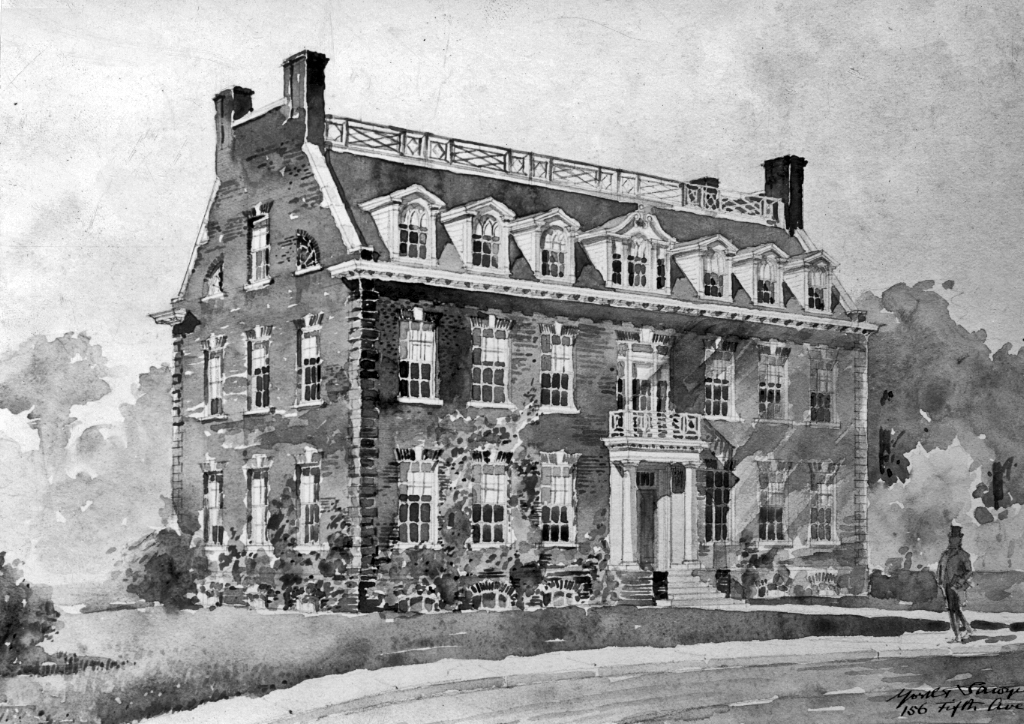

York and Sawyer

Before Swift Infirmary opened in 1900, Vassar had a small infirmary and convalescents’ room located in the southeast corner of Main Building’s fourth floor, staffed by the resident physician, her assistant and a few nurses. As the college expanded, in 1897 the physician, Dr. Elizabeth Thelberg, rented a nearby house for eight dollars a month to accommodate more patients. Two years later, the college began negotiations with the architectural firm York & Sawyer, the architects for the recently completed Rockefeller Hall, for a more permanent medical building, to be known as Swift Infirmary.

The building was given by his daughter Caroline Swift Atwater ‘77 in memory of Charles W. Swift—a lawyer and early mayor of Poughkeepsie, an initial supporter of the college, a signer of the its charter in 1861 and a trustee from 1861 until his death in 1877. At the time of the gift The New York Times said the college “owes much” to Swift, not “alone for his distinguished service but because he is said, more than any other, to have influenced Matthew Vassar’s decision to found a college for women.”

By 1900, construction on Swift Infirmary—or “Swift Recovery” as it was generally called—was well underway. Designed in the popular Colonial Revival or Georgian Revival style, Swift was the second of several buildings at Vassar designed by the fledgling architectural firm, York and Sawyer—after Rockefeller Hall (1898). The building featured a symmetrical layout with a chimney on each end and a decorative, molded cornice.

The interior consisted of various isolation chambers and examination rooms as well as a telephone system with three stations in Main B: one in the Physician’s Office, and one each in the apartment of the Physician and Assistant Physician, whose residences remained on Main’s fourth floor. This telephone system predated the implementation of Vassar’s campus system, which was functional as early as 1902, and far predated the development, in 1916, of outside telephone lines connecting the college to the greater New York area.

Vassar’s health facilities continued to expand after the construction of Swift: first with Metcalf House, the physician’s house, in 1915—also by York and Sawyer—and later, in 1940, with Baldwin Infirmary replacing Swift, which could no longer accommodate the needs of the larger and modern college. Once vacated in 1940, Swift was in high demand. Students, faculty and trustees called for its use for either academic or residential purposes. Since the college was experiencing a housing shortage, calls for a residential hall were particularly urgent; newer faculty members complained of the lack of adequate housing in the Arlington area and hoped to create temporary boarding rooms in Swift, while students complained of overcrowding in Main and requested Swift be converted into student housing. Despite these appeals, the trustees’ executive committee decided that for the 1940–1941 school year “the cost of alteration for student residence would be far in excess of the value of the building when completed for such purpose. A reasonable disposition of the building seems therefore to be for academic purposes.” The history department, the only academic department to apply for the temporary space, was granted the use of Swift for the year.

This was only a temporary decision, made until the trustees and President MacCracken could decide what Swift’s next purpose would be. Calls for extra housing for both faculty and students persisted. The foreign language departments—German in particular—also applied for the space, proposing to create a “Modern Language House” that would operate as the “German House” for two years and house fifteen students at a “negligible” cost, according to the joint proposal put forth by the German, Italian, and Spanish departments. The proposal further appealed to the success of German houses at other women’s colleges including Mt. Holyoke, Smith, New Jersey College for Women and Bryn Mawr. Still other proposals requested that administrative offices, such as those of the president, dean, warden, recorder and vocational bureau be moved from the front of Main to Swift, forming a central “administrative unit.”

Despite these various applications, the history department was approved by the faculty and the trustees to use Swift permanently as recorded in the December 1941 Executive Committee minutes:

“The President reported that the faculty had voted approval of the use of Swift by the Department of History. He called attention to the fact that this carries out the recommendation of the Trustees’ Committee on Faculty and Studies as recorded in the February 1940 minutes of the Trustees. The General Manager reported that exclusive of furniture, the estimate on the expressed requirements of the History Department it $2000. It is thought that sufficient furniture can be procured from various sources in the college.”

The department was likely granted Swift because of its pressing need for extra space to accommodate new visual resources such as microfilm and “original manuscript sources”—a need described by Professor Mildred Campbell, the chairman of the 105 History staff in a February 1940 letter to President MacCracken:

“At the present we are greatly handicapped in the use of this kind of material. Such facilities as we have,—the small conference room in the basement of the library, the bulletin board outside the history seminar, and a case in the basement of Rockefeller hall if one is free which it rarely is, are neither sufficient in space nor centrally enough located to permit their most advantageous use…. I need scarcely say that a central unit for the department capable of housing all these sections, and with proper facilities for making the best use of films, maps, and all such aids as we are convinced add life and reality to the study of history, would indeed be a boon.”

Relocating to Swift allowed all ten history professors to have offices under the same roof for the first time, and it also afforded the department enough classroom space to accommodate the roughly 450 students who elected to take history courses. Before 1940, the department only had priority rights to use three rooms in Rockefeller Hall and also held classes in the library classroom and Avery Hall. Professor’s offices were also randomly scattered throughout Rockefeller and Avery.

The building initially underwent virtually no renovation as it began its new function. The three old infirmary wards were converted into classrooms while the examination and isolation rooms were converted into additional classrooms and faculty offices. The second floor of Swift became an exhibition gallery, and, The Miscellany News reported, “Now, illustrative material, chiefly for 105, will be on display in the exhibition gallery on the second floor of Swift. Here students can now sit on a velvet-covered bench to meditate on Charlemagne’s contributions to culture.”

Swift’s refurbishment also featured seven Renaissance-style armchairs and some suits of armor “given to Vassar College by Mrs. J. Laurens Van Allen who inherited the estate of the late Frederick W. Vanderbilt” according to Professor Louise Fargo Brown’s November 1941 letter to President MacCracken. The armchairs were purchased for Mr. Vanderbilt from an Italian villa belonging to Count Bemo Bombicci Pontelli in the 1920s. The rest of Swift’s furniture was not nearly so extravagant. The college moved in 75 mismatched chairs from Rockefeller along with a number of chairs and bookcases from Avery Hall. Additional chairs were purchased for $6.30 each and seminar and classroom tables were purchased for anywhere from $85.67 to $29.91 depending on their size. Despite seeking appraisals for a sprinkler system to be installed in the attic, basement, and hallways of the building, Swift remained one of the only buildings on campus without sprinklers because Vassar’s General Manager, Keene Richards, considered the lowest estimate, $5,325, to be “very much inflated.”

Swift remained essentially unchanged—except for minor renovations and updates in the late 1960s and again in the 1990s—until its gradually sinking foundation rendered complete restoration and renovation necessary in 2012. Designing the infirmary in 1900 to support relatively lightweight use, York & Sawyer could hardly have anticipated its transformation into a full-time academic building, filled to capacity week after week and year after year. As it passed its hundredth year, the building had settled about three inches since 1941. Its renewal, completed in August 2013, took a little over a yar and cost just over $4 million. The renovation was partially funded by alumnae/i donations from the sesquicentennial’s “Vassar 150: World Changing” campaign.

Swift’s classic Georgian façade was preserved and restored, but the building’s interior was completely redone. Three additional offices were built—at the sacrifice of two classrooms—so that all 17 history professors could have their offices in Swift. The remaining two classrooms were updated with new document cameras and matching desks and chairs. Air conditioning was also installed in the building (faculty offices boasting the capability for individual climate control) as were new power and plumbing systems. A ramp was incorporated into the building’s front entrance to accommodate handicapped students.

Throughout the changes, Swift Hall has rigorously maintained the original character of “Swift Recovery,” played an integral role in student life, and remained one of the college’s most distinctive buildings.

Sources

Van Lengen, Karen and Lisa Reilly,The Campus Guide: Vassar College, Princeton Architectural Press, 2004.

Historical Sketch of Vassar College.” The Vassar Miscellany, 1 Aug. 1878.

“Revamped Swift Is Hall of History.” The Miscellany News, 8 Oct. 1941.

Cruz, Jon. “The Vassar Chronicles: History of the History Department.” The Miscellany News 25 Oct. 2002.

Leighton Suen, “College Presents Plan for Infrastructure Improvement.” The Miscellany News, 5 Apr. 2012.

Bleifuss-Prados, Eloy. “Swift Hall keeps historic façade after new renovations.” The Miscellany News, 19 Sept. 2013.

Ringel, Lance. “Returning to a ‘New’ Swift Hall.” The Vassar Alumnae/i Quarterly. Fall 2013.

Executive Committee Minutes Jan. 1894-Dec. 1909. (VCSC).

Executive Committee Minutes 1932/1933–1938/1939. (VCSC).

Executive Committee Minutes 1939/1940–1945/1946. (VCSC).

“Committee on Swift,” Henry Noble MacCracken Papers 47.35. Vassar College Special Collections (VCSC).

“Swift Infirmary,” Henry Noble MacCracken Papers 19.32. (VCSC).

“Swift 1940-41,” Vassar College History Department.

Campbell, Mildred C. “To the Committee appointed to investigate the use of academic buildings.” Dated 6 May 1940. Swift 1940-41 Vassar College History Department.

Kohl, Benjamin G. “Swift Recovery (A brief history of Swift Hall),” Dated 11 Apr. 1995. Vassar College History Department.

CG, 2014