Cushing House

Cushing House (1927)

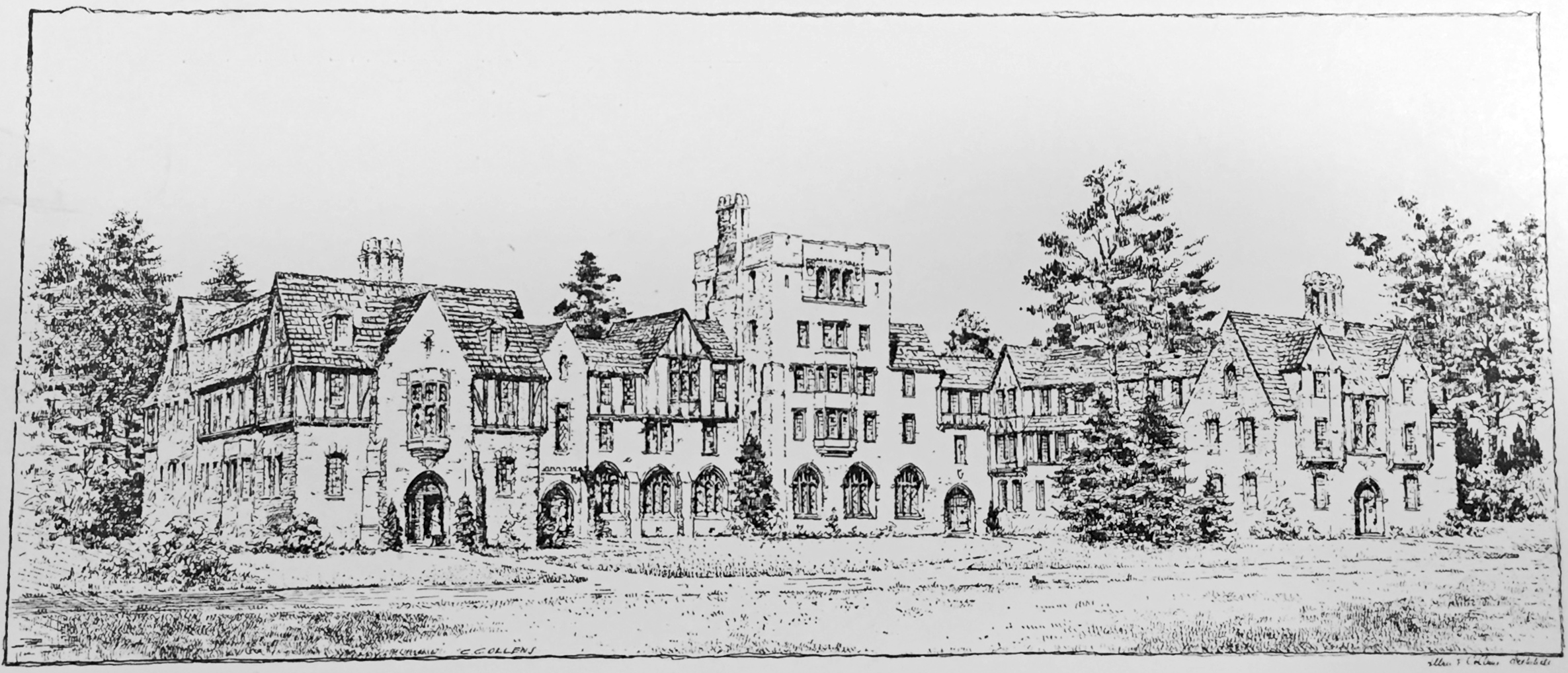

Allen and Collens

In a letter to President Henry Noble MacCracken in February 1926, the college warden, Jean Palmer ‘93, wrote, “Vassar is appearing as an exponent of euthenics and the present living conditions seem inconsistent….” The concept of Euthenics was defined by Ellen Swallow Richards ‘70 in The Cost of Shelter (1905) as “the science of better living,” and she set forth the principles of the new science in Euthenics: The Science of Controllable Environment (1910). President MacCracken was a strong proponent for Richards’s ideas and an advocate for introducing them into the curriculum and for developing facilities to accommodate them. Entering the curriculum in 1925, the euthenics program, an experiment in multidisciplinary studies, sought to interpret the studies and methods of the emerging social sciences into what was seen as the “women’s sphere.” “MacCracken,” historian Elizabeth Daniels ’41 has noted, “did not see his program as returning women to domesticity and thought that as it expanded it would liberate them to have an enhanced impact on social change and to improve the quality of lives in home, community, nation, and on the globe.”

But in 1925, the college was faced with a more commonplace problem. There were not enough rooms for students on campus, resulting in many having to live off-campus in small wooden houses, the conditions of which were less than inviting for the young women. Between 1920 and 1925, nearly one third of the students were living off-campus. With the growth of the euthenics movement (an academic department at Vassar until 1958), there was much concern that such a disconnected and confining living situation would be damaging to the development and curricular opportunities of the students. In the spring of 1925 the trustees voted to bring all entering freshmen on campus, requiring that some of the faculty move from the residence halls, and the following fall the Miscellany News, suggesting that the incoming freshmen “have perhaps accepted” the inadequate housing “as a necessary evil,” asked “How long will that evil be necessary?”

The answer was soon in coming. The trustees authorized the erection of a new residence hall the following month. In addressing this problem, MacCracken envisioned a residence hall designed to accommodate the practices of euthenics. Cushing House (1927), the Wimpfheimer Nursery School (1927), Blodgett Hall (1929) and Kenyon Hall (1936) were conceptualized as a euthenics ensemble, seeking to house all aspects of the program on the northeast side of campus. The need for housing was so great that Cushing was begun with only part of its total $500,000 cost in hand. The additional funding was obtained through donations made in response to a well-organized campaign to engage alumnae and other prospective donors.

MacCracken’s original residential plans called for a quintessential “village enclosure in the Old English style,” consisting of eight small cottages surrounded by a brick wall. This arrangement would facilitate the study of euthenics, as, he wrote, “…each building could be used as a home unit for purposes of observation and experiment within the department of nutrition, hygiene and home economics.” Although this vision did not come to fruition, the building that materialized carried many evidences of his thoughts on functionality.

“The style will be English 16th century, which will harmonize with the Warden’s house. It will be in the form of a double dormitory three stories in height and somewhat irregular in shape, with separate dining and living rooms for 70 students in each half of the building.”

Miscellany News

Cushing was designed by Allen and Collens, the New York City firm that had designed the Frederick Ferris Thompson Memorial Library (1905), Taylor Hall and Taylor Gate (1915) and the Wimpfheimer Nursery School (1927). Their design presented a sixteenth century English cottage-style building that respected the nearby presence of the Tudor revival Pratt House (York and Sawyer, 1915) in which the head warden, Jean Palmer lived. The new three-story building was to house 130 students, all except four having single rooms. While this would not allow for an increase in the number of students at the college, it would provide some much-needed respite for residence halls bursting with the 1150 students.

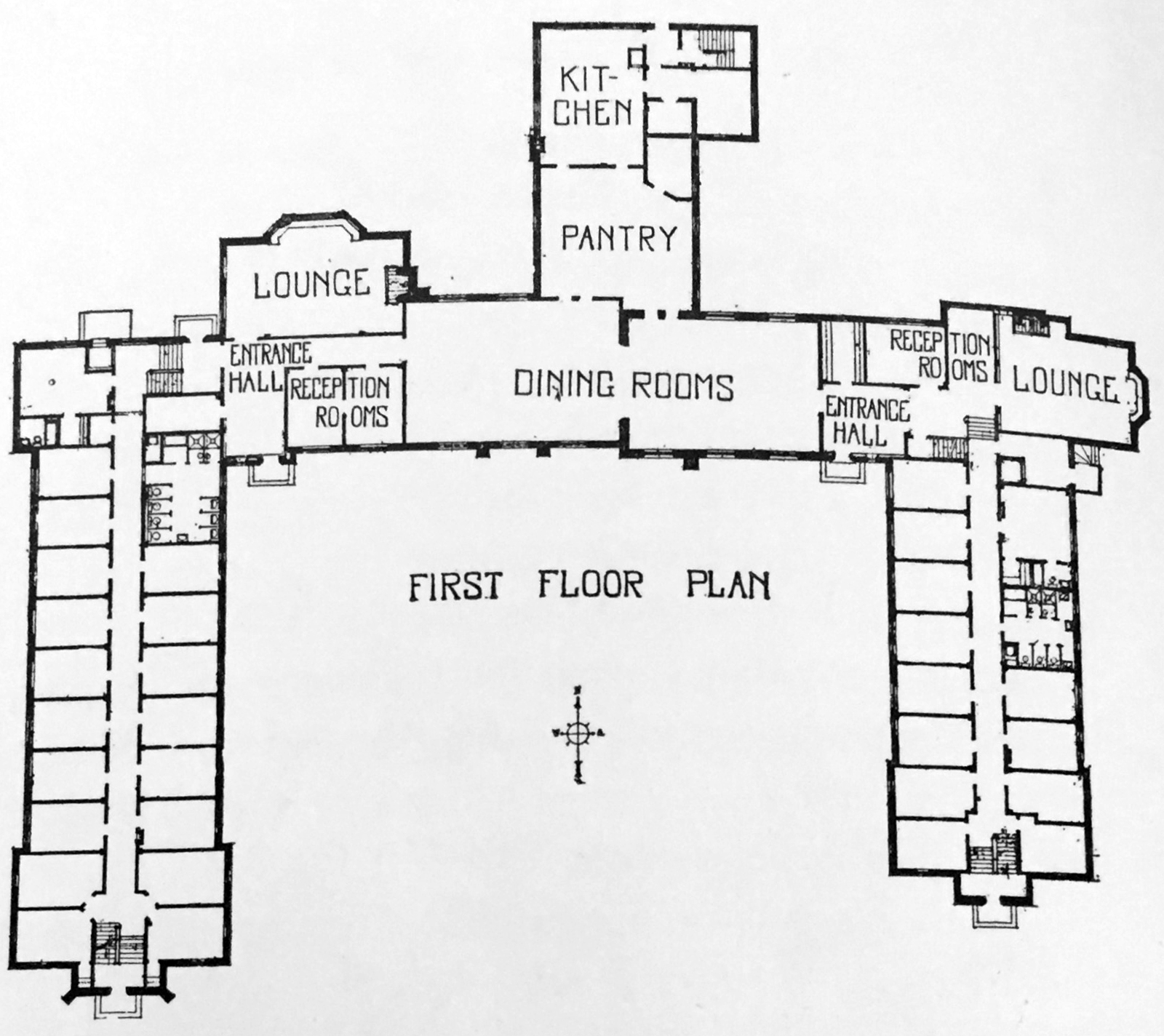

The design was symmetrical and relatively simple: two wings connected by a transverse section. Erected on the site of the old tennis courts, which were relocated to the western and eastern sides of the campus, Cushing was conceived of as two separate buildings. President MacCracken explained this plan to Miss Palmer in February 1926. “The present form was dictated not only by the wish to reduce the noise and crowding of large halls in both lounges and dining room, but also because one-half of the building could be erected at one time as an entirely adequate edifice.”

The first floor was to have plenty of space for socializing: two dining halls and two lounges, one for each half of the building. A single, large kitchen and pantry between the dining halls, and the halves had separate entrances and reception rooms. The second and third floors held rooms for students, while the section over the kitchen and pantry, known as the servants’ quarters, was reserved for the accompanying help.

Practicality was a main staple of the eventual building’s design, as the college’s general manager Keene Richards outlined in a letter to President MacCracken in April of 1928. “I believe this building to be as strictly utilitarian as the average factory structure, considering the purity of each, and I am sure that a careful analysis of this structure and its equipment will convince anyone that it is neither luxurious nor extravagant.”

Students’ opinions were solicited in the design and execution of the new residence hall. Campus surveys showed most young Vassar women preferred bathtubs to showers and wanted long mirrors and appliances in the bathrooms for curling hair. Students also requested both cold and hot water in any showers that were added. The interior decorations and furniture were carefully chosen in order to reflect efficiency and comfort. Each room was to be outfitted with a divan from the Boston firm, R.H. White, a Simmons “BeautySleep” mattress, a four-drawer chest with mirror, a writing table, a desk chair and an arm chair in the Windsor type. The rooms were to be floored in linoleum in a “Jaspe” pattern and the halls by green square linoleum, as stipulated by Collens. In January 1927 the chairman of the Committee on Furnishing the Dormitory, Margaret Jackson Allen ‘01, reported to the committee about her communication with the several vendors of items of interior decoration. “All have submitted further samples of color than those shown the committee in the December meeting, and your chairman has done her best, God help her, to decide which the committee and the students and the faculty and the wardens and the parents and the administrative officers and the visiting chambermaids would find the most restful and delightful color to the eye.”

Cushing House welcomed its first residents on September 23, 1927, three days after the sudden death—from pneumonia, at her summer home in Norwell, MA—of its namesake, Florence Cushing ’74. The valedictorian of her graduating class, the Boston native had served the cause of women’s education in many ways. A founder of Girls’ Latin School in Boston and the Association of Collegiate Women—later the American Association of University Women, she had been a tireless worker for her alma mater.

It was through Cushing’s work that in 1887 the alumnae petitioned for and were granted representation on the board of trustees. Elected the first alumna trustee, she served on the board from 1887 until 1893 and again from 1906 until her retirement in 1912, when she was elected a “trustee emerita.”

When she was notified that the new dormitory was to be named after her, Cushing qualified her acceptance in a letter to Helen Kenyon ’05, a trustee: “I am covered with confusion when I think how little I have ever done for the College to merit such appreciation. I simply cannot believe it for I know how absolutely undeserved it all is…. But I must beg one favor, that this building shall always be thought of as a commemoration of the action of the Trustees, led by our beloved Dr. Taylor in the first year of his presidency. It took some courage at that time for the members of the Board to give up even a shred of their trust. You are too young to remember how serious a thing it seemed to them to give voice and vote to any woman, especially, to a young and untried alumna…. It is because of my gratitude for Dr. Taylor’s courage and the Trustees’ willingness to follow that I am content to have the building bear the name of the alumna trustee first selected. For this and this only. Will you see that this is fully understood?”

Miss Cushing was similarly modest in a letter, on February 17, 1927, to President MacCracken: “I cannot speak my gratitude—that is beyond me…. What had I ever done for Vassar to call forth such a meed! Nothing except the commonplace which falls in the day’s work. But there was the writing before me and I could only humbly accept what was so graciously given.”

Cushing House was formally dedicated on Saturday, October 29, 1927. President MacCracken, reported the Miscellany News, “told of the gradual growth of the college which necessitated the building of a new dormitory and thanked all those who in plans, manual work and loans had helped erect the building.” He also drew attention to a model of the memorial bronze tablet honoring Florence Cushing which was to be placed in the entry hall of the new building. The two other speakers at the dedication were Laura Brownell Collier ’74, a classmate of Cushing, and Marion Coats ’07, the founding president, in 1924, of Sarah Lawrence College.

Alterations have affected the building over time, reflecting the changing needs of its student residents. The two dining halls were combined into what is now known as the Great Hall, a large open space used for studying and relaxing. The back pantry and kitchen is now the house fellow’s residence, and the servants’ quarters have been made into single rooms. The dormitory retains the functionality of President MacCracken’s little village while being recognized as one of the favorite spaces on campus. Known for its homey atmosphere and welcoming community, Cushing stands as a reminder of the past ideals of the college and their focus on the accommodation and betterment of the student body.

Related Articles

Sources

Daniels, Elizabeth, Main to Mudd and More. Poughkeepsie: Vassar College, 1996.

Van Lengen, Karen and Lisa Reilly, The Campus Guide: Vassar College. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004.

“A New Dormitory,” Vassar Miscellany News, vol. X, no. 6, 14 October, 1925.

“Construction of New Dormitory Begins At Once,” Vassar Miscellany News, vol. X, no. 30, 20 February 1926.

“Miss Cushing Dies Suddenly,” Vassar Miscellany News, vol. XII, no. 1, 1 October, 1927.

“Home for Euthenics,” Vassar Miscellany News, vol. XIII, no. 24, 16 January, 1929.

Subject File, Cushing House, Vassar College Special Collections Library

Subject File, Vassar College Historian’s Office

GM 2015