Natural History Museum

As Matthew Vassar was beginning to think about his college, a new method for science education was taking hold in America, a shift from conventional lecture classes to the understanding that first-hand observation and experimentation is essential to learning. In 1862 Vassar commissioned a so-called ‘cabinet’, or collection of scientific specimens, knowing that in order to keep up with their male counterparts, the women of Vassar would need to study the material first-hand. He wanted the students to have access to primary materials—to see, touch, and fully understand the substances they were studying. Consequently, Vassar’s first president Milo P. Jewett and his board of trustees, determined to establish a truly great collection, set out to hire the most qualified individual to take on the position of cabinet creator.

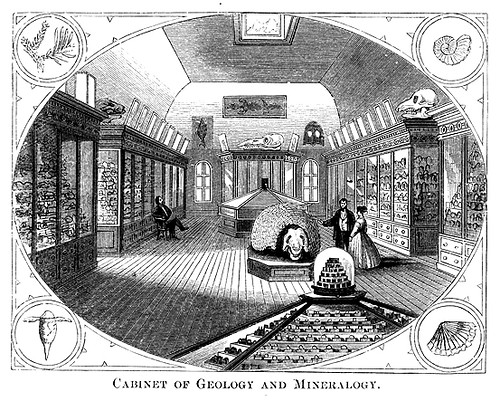

In late 1862 the trustees hired Henry A. Ward, a professor of natural sciences at the University of Rochester, to put together the cabinet. Ward, who had already established an impressive collection at Rochester, as well as his own personal collection, saw himself as a “museum builder,” and took to the endeavor enthusiastically. Ward’s cabinet, conceived of as a teaching tool comprised mostly of geological and mineralogical specimens, was installed by 1864 and was housed in Main Building. Shortly after the completion of the museum, a respected state geologist, James Hall, and a professor of natural sciences at Yale, James D. Dana, inspected the cabinet and remarked that the collection was “exceptional,” surpassing anything they had seen in the United States or Europe.

In 1865 Sanborn Tenney was hired as Vassar’s first professor of Natural History, as well as the first curator of the Collection. Tenney had graduated from Amherst College in 1853 and subsequently studied under famed scientist and vocal opponent of Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, Louis Agassiz. Tenney, who like Agassiz was a creationist, looked at science—and consequently the Collection—as a means of showing “God’s Great Ability.” In 1869 Tenney left Vassar for a professorship at Williams College, thus creating a vacancy at Vassar that the eminent naturalist James Orton would fill. Orton, who was a long-time friend of Henry A. Ward (and, incidentally, of Charles Darwin), would serve as professor of natural history, and curator of the Collection from 1869 until his tragic death in 1877 while on a collecting expedition to Peru.

In 1874 the college, in order to create more space in Main Building for students, decided to move the Collection to the nearby Calisthenium and Riding Academy, as the Riding Academy had been closed. On February 22, 1875 the newly named Vassar College Museum of Natural History celebrated its grand opening, one of the evening’s guests was Louisa May Alcott, whose presence on campus created a bit of a commotion, as students swarmed the author in hopes of attaining an autograph.

The Museum underwent many significant changes under Orton’s care, including the addition of a large number of zoological and biological specimens. The Museum became home to numerous historically and scientifically important artifacts and included an comprehensive assortment of books about birds, the subjects of which ranged from the aesthetic lure of birds to scientific discussions of migration, anatomy, and physiology.

One of the greatest possessions in the collection was a specimen of the extinct bird the Great Auk. The Vassar Auk was of particular importance because it was the specimen that John James Audubon had used in his descriptions of the bird. In 1920 the Great Auk, as well as some of the Museum’s other prized birds, including an another extinct bird, the Labrador Duck, were sent on loan to the Museum of Natural History in New York City. In 1965 the Great Auk and the Labrador Duck were sold to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where they remain today.

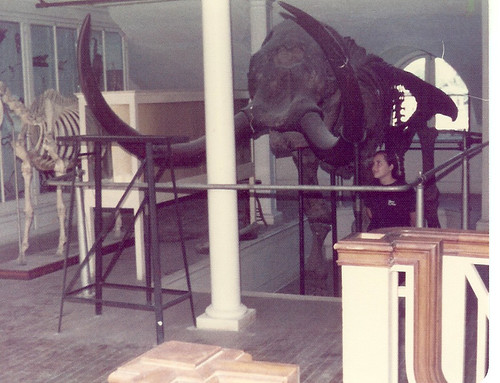

In 1878 William Buck Dwight was hired as Vassar’s new natural history professor and curator of the Museum. Dwight, more than anything, wanted a mastodon for the collection, so he set out to assemble one by collecting bits and pieces of different mastodons from around the country. Topped with the skull of the Circleville mastodon purchased from the University of Ohio, Dwight’s creation was twenty feet long and nearly nine feet tall. In 1918, in order to create more classroom space, the Museum was moved to the New England Building, where the mastodon stood until the 1980s, when yet another move forced the Museum to disassemble and move the mastodon to the State University of New York at New Paltz, where it remains, sadly, lying in disarray.

The Museum in the New England Building extended from the first floor to the third, with collections being displayed both on the stair landings as well as in the central hall of the third floor. The impressive collection included nearly 3,000 mounted birds, a majority of the North American species, most of which were gathered together by James Orton and Poughkeepsie resident Jacob P. Giraud.

The 1950–1951 Guide to the Museum of Natural History, by then curator Rudolf T. Kempton, describes the layout of the museum: On the landing between the first and second floors was the collection of Embryological Models, which displayed the various stages of embryonic development of many animals, both invertebrates and vertebrates such as frogs, birds, monkeys and even humans. The second floor was dedicated entirely to the museum’s impressive collection of birds. Included was a specimen of the endangered New Zealand Apteryx (also known as the Kiwi), and the Great Auk. The third floor was home to the main exhibits of the museum, which were displayed in separate cases including: A Survey of the Animal Kingdom, Birds, Mollusks, Local small animals, Mammals (primates), Mammals (local carnivores and rodents), Water living animals, Bird eggs, and Comparative Anatomy of Vertebrates. As Kempton explains, the displays were arranged in such a way as to show the “evolutionary history and relationships of animals, the characteristics basic to relationship, and the binomial system of nomenclature.”

In addition to the cased specimens, there were also several skeletons on display, including specimens of Mastodon, horse, cow, pig and deer. The main exhibit also housed taxidermy displays of the sea turtle, a famous game fish, the tarpon (which was an impressive 6 feet, 6 inches long and weighed about 187 pounds), and the American Bison. Additionally, models of extinct animals, such as relatives of the elephant, and a saber-toothed tiger were also on display. The main exhibit also housed a large collection of insects and parasites.

In the 1970s the Museum was forced to dispose of a large number of artifacts, including a full-size walrus and the buffalo, because they had not been properly taken care of and were infested with insects and mice. A young woman who was working at Vassar at the time found the walrus and buffalo in the dumpster and decided to take them home, where they remained on her lawn, slowly disintegrating until all that was left were the walrus tusks, which were returned to Vassar in the summer of 2006.

In 1973, with the opening of the Olmsted Hall of Biological Sciences, a biology department combined for the first time the departments of physiology, zoology and plant sciences, all with varying interests in museum specimens. Additionally, curricular changes brought about the need for space: studio art, a former poor relation to the art history curriculum in Taylor Hall, was gaining in importance and took over the 3rd floor of New England.

Margaret Wright, the former museum curator and the person largely responsible for finding new homes for the specimens in the museum’s collection, explains that in early 1979 Vassar administrators made the decision to start phasing out the museum due to “lack of space,” and the growing financial burden of running a museum. She speaks of the changing needs of the scientific departments, stating, “everyone [in the Biology department at Vassar] was centered on active research and tended to disregard the value and history of the museum.” Wright recalls very fondly the museum’s impact and place at Vassar and in the greater Poughkeepsie community. The museum was a popular field trip destination for many schools in Poughkeepsie: “At one time every child in Poughkeepsie had been taken to the museum…classes, scouts, anything you can think of—every kid knew about it, it was very popular.”

With the closing of the Museum, the collections were distributed among various organizations, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the Museum of Natural History in New York City, the State Museum at Albany, the Trailside Museum in Westchester County, and Dutchess Community College. Additionally, many of the bird specimens were given to the Audubon Society, but a few are displayed at Vassar in Olmsted Hall.

In 1992 what was left of the museum was moved to the first floor of Ely Hall. In April 2006 the museum, now called the A. Scott Warthin Museum of Geology and Natural History, celebrated its re-opening, complete with a newly renovated space and new display cases. The Administrative Assistant of Ely Hall, Lois Horst, explains, “What’s left is what we started with—minerals and geological specimens. Lots of fossils, rocks, minerals, [and] antique equipment that were used for study.” Horst also explains that the geological collection is one of great importance and financial worth, as many of the specimens were gathered in the 1860s and 1870s and can no longer be found. The main goal of the museum today is the same as Matthew Vassar’s original goal—to provide students with an outstanding, hands-on educational tool.

Related Articles

Sources

Kempton, Rudolf T, “The Guide to the Museum of Natural History 1950–1951.” Vassar College Special Collections, Subject File 20.36.

Interview with Margaret Wright, December 2006.

Interview with Lois Horst, May 2007.

EMS 2007