The Folklore Foundation

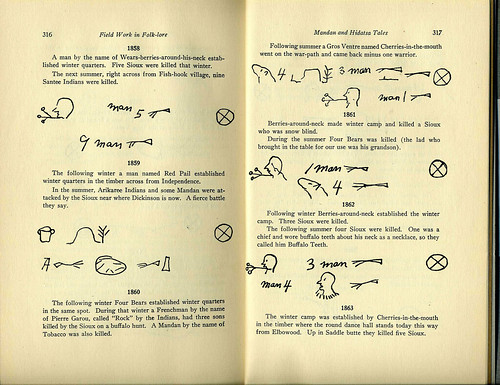

The Folklore Foundation arrived at Vassar in 1920 with Martha Beckwith, a folklorist who studied under Franz Boas, the famous anthropologist, at Columbia. Considered remarkably progressive at the time, the project studied and examined all “folk” elements of culture from folk tales, to folk dancing, to slang. While the foundation conducted research on a wide variety of areas of the world, it focused on Hawaii, Jamaica, the Hudson Valley, and the Native Americans of the Dakotas.

Most of the Foundation’s responsibilities did not involve teaching. Its charter noted, “The folk-lore foundation is not established primarily as a teaching post. Its aim is to furnish a center at Vassar College for scientific research into the field of Folk-Lore.” The Foundation therefore only had typical classroom interaction with the students in the two folklore seminars Beckwith taught each year. However, Beckwith attempted to bring folklore to the attention of the campus in other ways. She invested money in the Foundation Library, an open research resource, filling it with every book or article on folklore or anthropology that she could afford. The Foundation also sponsored lecturers, performers, and in 1932 even invited Hawaiian girls to speak on campus.

The foundation also published a journal annually. Between 1920 and 1934, fourteen issues of Vassar College Publications of the Folk-Lore Foundation, Titles included everything from “Folklore in America,” to “Notes on Jamaican Ethnobotony,” and although most represented Beckwith’s work, a number were by other authors associated with the foundation. Beckwith explained, “Our purpose is to publish one number annually which will embody purely objective material fresh from the field rather than theoretical studies, and which will therefore contain, however slight, a genuine contribution to folk lore.” Paid for mostly by alumnae sponsorship, the publication became financially insoluble in 1934 and ceased publication.

The journals seem to have become more popular than initially expected, as a number of institutions requested copies of the publications they had been unable to obtain. Although much of the interest originated from places like Harvard and the University of Chicago, not all the institutions were academic. The Physical Education Department of America wanted a copy of “Folk Games of Jamaica,” and children’s magazines across the country asked for copies of “Hawaiian String Games.” Interest extended outside the country as well. In 1934, the Foundation received a letter from Wen-tsau Wu, professor of Sociology at Yenching University in China, requesting copies of the publications. He believed that the kind of research Vassar was conducting was particularly pertinent to China: “…I am convinced that the key to understanding Chinese village community life is through the anthropological approach, and folklore study will constitute an essential part of this line of approach.” The Foundation also had correspondents throughout Europe.

Beckwith attempted to involve both students and alumnae in Foundation’s work. Some students simply became involved through class work: Beckwith required each student in her folklore seminar to gather her own collection of folk-tales or sayings, no matter how insignificant. Other students became more heavily engaged, accompanying Beckwith on her summer trips to Native American reservations, or submitting portrayals of people they encountered in their own travels. Through the Foundation, the future composer Helen Roberts visited Jamaica to study and record local music during her student years at Vassar. Her musical transcriptions accompany many of Beckwith’s articles in the Foundation’s publications.

Alumnae involvement was in some ways even more significant. The Foundation’s pamphlet issued an open invitation: “The alumnae are invited to submit to the President… any individual plans for field work the special opportunity for which may open through travel or environment… or to communicate work already collected…. The alumnae are urged, when in foreign countries, to collect for the foundation library such local publications in folk-lore books of travel or fairy tales, or journals of local societies.” Alumnae responded to her request, sending copies of local books, long descriptions of tale-telling or slang in the places they visited, or more professional transcriptions of field research. Some even wrote articles or books associated with the Folklore Foundation. In 1938, Constance Varney ’21 published a book containing edited versions of many of the tales of the Hudson Valley gathered by generations of Vassar folklore students.

For the eighteen years it existed, the Foundation put Vassar at the center of a very new kind of study. Beckwith pleaded with the college to hire a professor to continue the folklore seminar after she retired, noting that the college had gained a reputation in the field. Financially, this was impossible. However, during its relatively brief existence, the institution produced a remarkable scholarship and some excellent scholars. Moreover, anthropology at Vassar was in the process of expanding. Although anthropology courses had been offered in the Zoology department beginning in the mid-twenties, in 1939, anthropology became a separate department with course offerings that grew by the year. This department would ultimately continue research similar to the kind the Foundation introduced to Vassar in the twenties.

A Financial History

After Beckwith received her Ph.D., her childhood friend, the naturalist and sugar heiress Annie Alexander, offered to donate an anonymous fund that would allow her to pursue the research into Hawaiian folklore she had begun at Columbia. Because the fund required an institution to monitor and accredit it, Beckwith asked the English department at Vassar if it would be interested in providing space for a foundation dedicated to the study of folklore and folk culture. The English department agreed and accepted the fund, although no one besides Beckwith knew the donor’s identity. Vassar hired Beckwith as the Research Professor of the Folklore Foundation and as an Associate Professor of Comparative Literature. The arrangement worked rather well, and at the end of the promised five years, the college approached Alexander about the possibility of extending the donation. Alexander agreed to continue it, initially on a yearly basis. By 1927, however, she guaranteed her financial support for the length of Beckwith’s association with the college. Vassar and Beckwith nearly succeeded in convincing Alexander to make the donation permanent before the stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression made it financially impossible.

Related Articles

Sources

Beckwith, Martha. “Folk-games of Jamaica.” Vassar College: The Folklore Foundation, 1922.

Beckwith, Martha. “Folklore in America, its Scope and Method.” Vassar College: The Folklore Foundation, 1931.

Beckwith, Martha. Hawaiian Mythology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1940.

Beckwith, Martha. The Kumulipo, a Hawaiian Creation Chant. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951.

Beckwith, Martha. “Notes on Jamaican Ethnobotony.” Vassar College: The Folklore Foundation, 1927.

Green, Laura S. “Hawaiian Stories and Wise Sayings.” Ed. Martha Beckwith. Vassar College: The Folklore Foundation, 1929.

MacCracken, Henry Noble. The Hickory Limb. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950: 67.

“Martha Beckwith.” Biography File, Special Collections, Vassar College Library.

Springer, Patrick. “Unlikely Savior: Vassar Prof Recorded Tales of Disappearing Culture.” The Forum 17 September 2003: https://www.in-forum.com/specials/DyingTongues/index.cfm?page=article&id=38697&tribe=Mandan.

Stein, Barbara. On Her Own Terms: Annie Alexander and the Rise of Science in the American West.” Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

“Vassar College, Folk-Lore Foundation.” Correspondance, 1919–1938, Special Collections, Vassar College Library.

CBC, 2005