Con Spirito

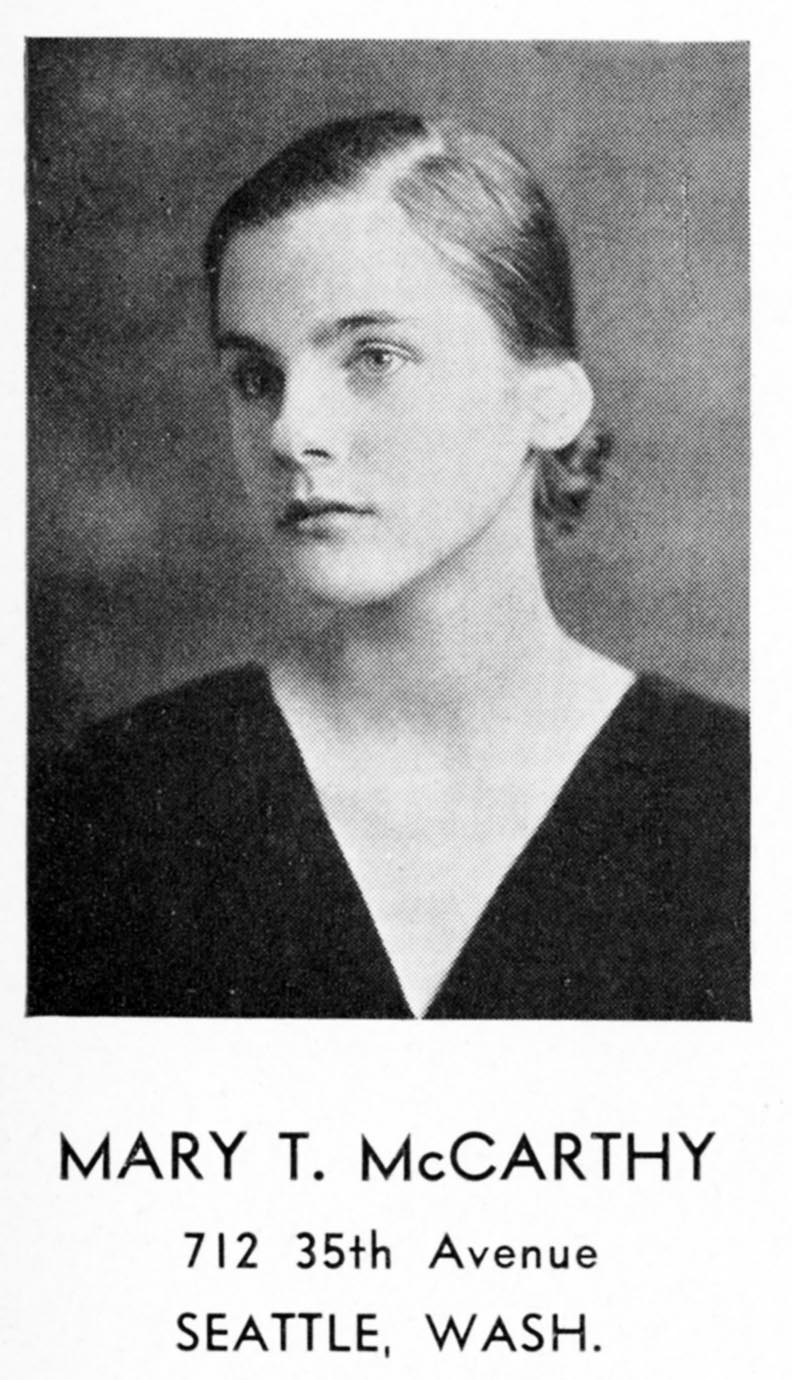

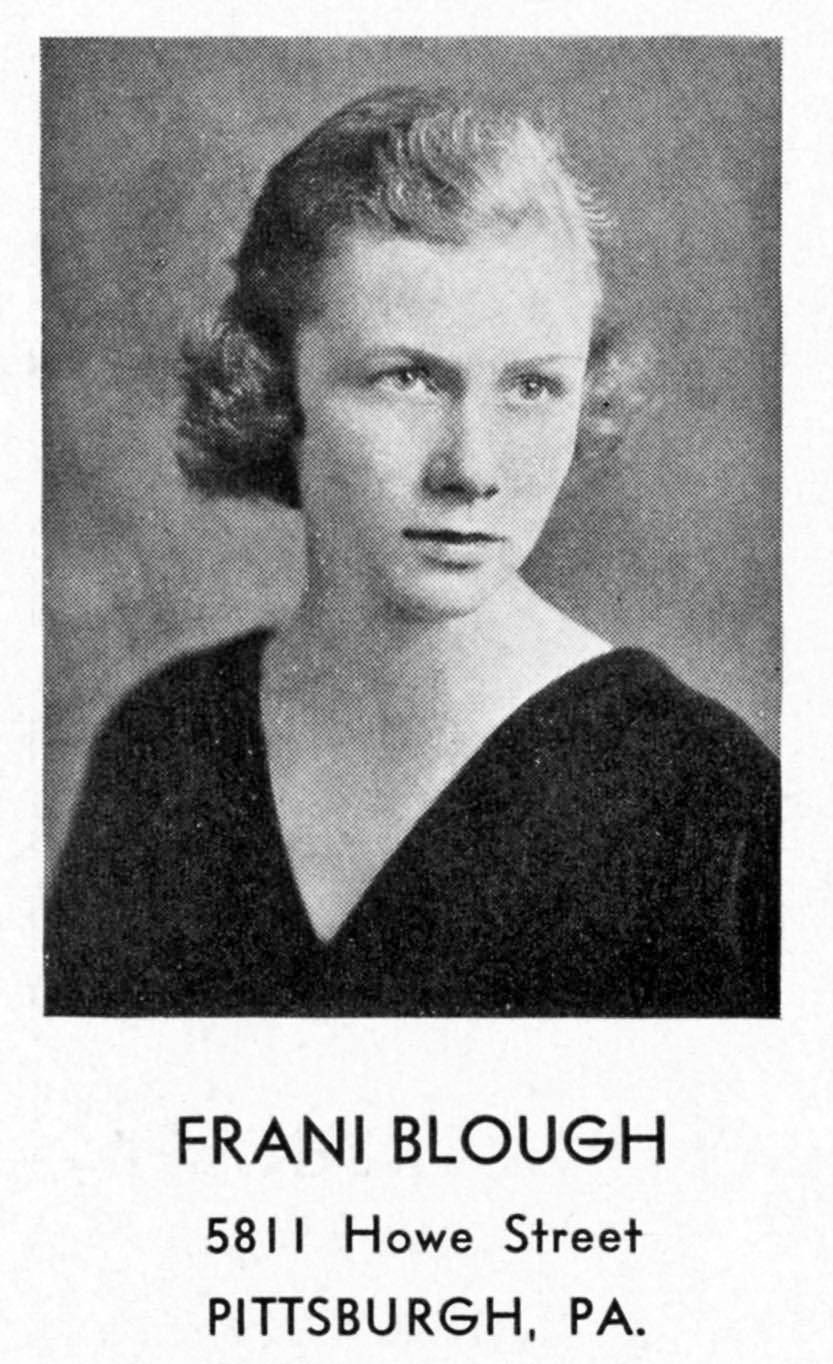

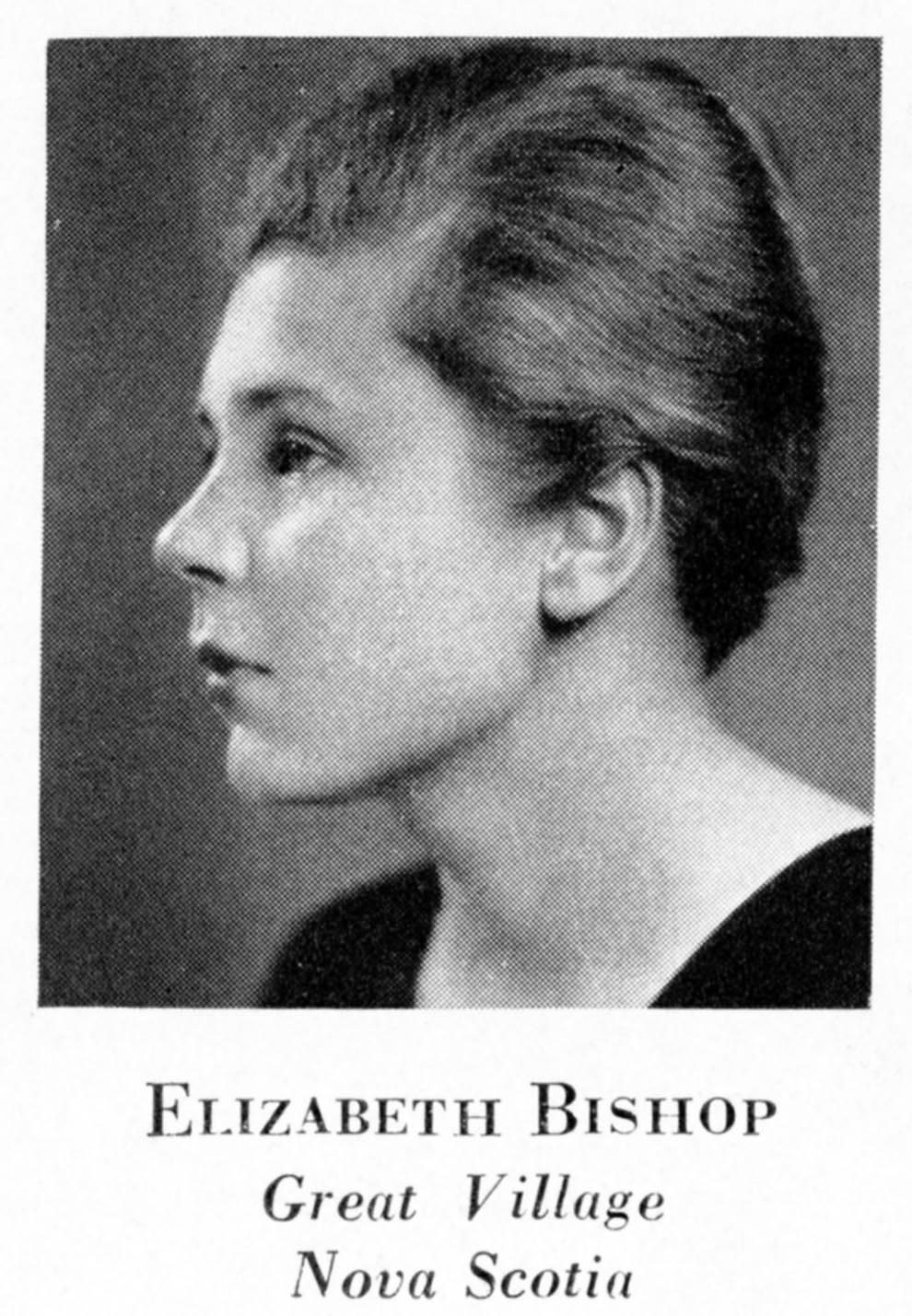

In early 1933, Mary McCarthy ’33, Elizabeth Bishop ’34, Frani Blough ’33 and sisters Eleanor ’34 and Eunice Clark ’33, created a rebellious, anonymous literary newspaper called Con Spirito. “It is really going to be good,” Blough prophesied before its publication, “a little shock at the Review! Nothing tame, arty, wishy-washy, ordinary or any of the other adjectives applicable to so much college writing.”

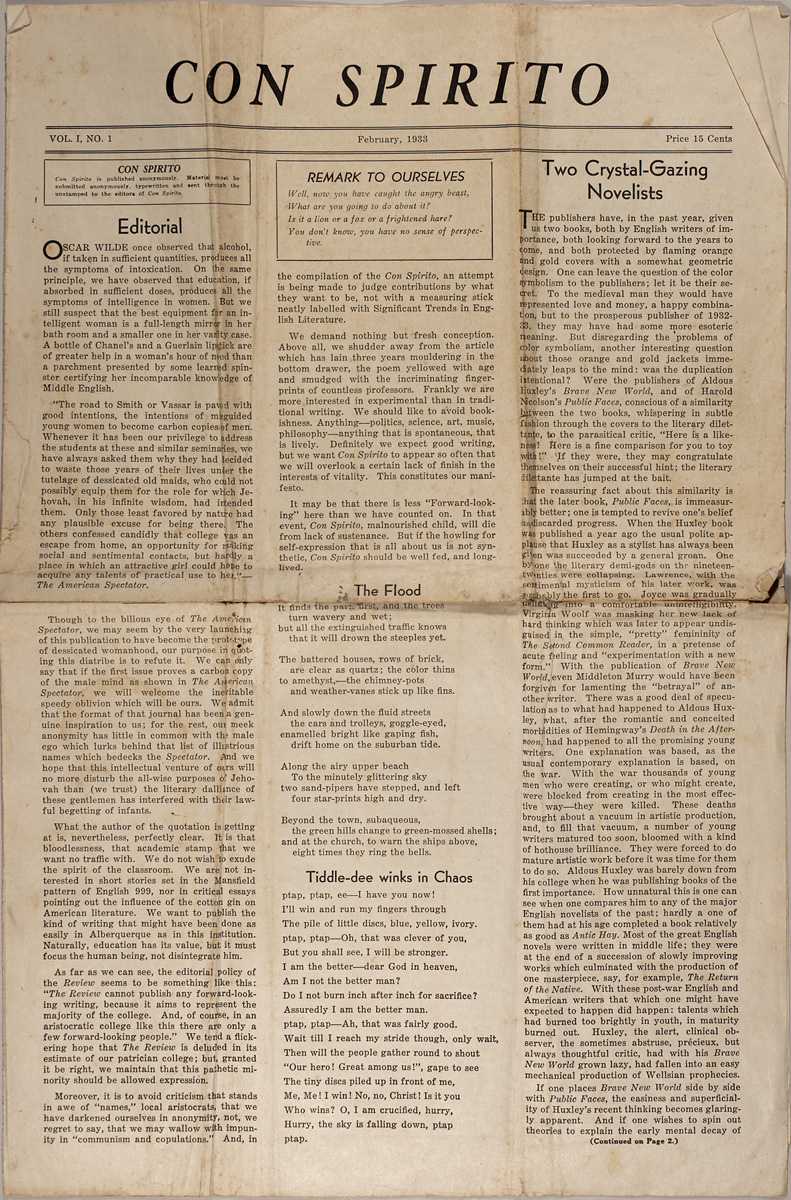

The editors distributed information about the forthcoming publication in February, posting advertisements on tree trunks around campus, distributing them to selected student mailboxes and publishing them in The Miscellany News. “Material must be submitted,” they announced, “anonymously, typewritten, and sent through the unstamped to the editors of Con Spirito…we demand nothing but fresh conception.… Frankly, we are more interested in experimental than in traditional writing. We should like to avoid bookishness. Anything—politics, science, art, music, philosophy—anything that is spontaneous, that is lively.” In a letter to a friend in December, Bishop’s version of the journal’s rationale was less lofty. Con Spirito, she said, was “an attempt to startle the college and kill the traditional magazine.”

The announcement and publication of Con Spirito and its antipathy—implicit and overt—towards the longstanding Vassar Review incited a minor uproar on campus. Many years later Mary McCarthy told Elizabeth Daniels, “It created a sensation—and I think we put affiches on the trees, if I remember right, little posters for it, like hobgoblins, and we were amusing ourselves being very gay, and this general reaction of shock and horror, of Vassar, rather painful and comical.” Generally satirical and sarcastic, Con Spirito published nothing overtly offensive, but its avowal of rebellion troubled some faculty members. McCarthy speculated that her mentor and the current chair of the English department, Helen Sandison, well aware of who had produced the journal, supported her students in response to colleagues’ misgivings about Con Spirito.

Con Spirito aimed to push against the literary, scholarly and social boundaries of college life. In her memoir How I Grew, McCarthy—who wanted to call the paper The Battle Axe—remembers that Bishop chose the name Con Spirito to imply the unconventional, conspiratorial image the editors wanted to project in their publication. They even mirrored this desire in their editorial routine. At first the group met, like other student organizations, in the Students’ Building, but they quickly moved to a speakeasy off campus, where they daringly drank red wine out of white coffee mugs as they plotted to break conventions for student writing at Vassar in content as well as in form.

An editorial in Con Spirito’s first issue, dated February, 1933, mockingly responded to one published in January 1933 in the first issue of the American Spectator, a short-lived monthly “literary newspaper” edited by critic George Jean Nathan and an editorial board that included, among others, novelists Theodore Dreiser and James Branch Cabell and playwright Eugene O’Neill. “The road to Smith or Vassar,” the Spectator proclaimed, “is paved with good intentions of misguided young women to become carbon copies of men. We have always wondered why they decided to waste those years of their lives under the tutelage of dessicated old maids, who could not possibly equip them for the role for which Jehovah, in His infinite wisdom, has intended them. Only those least favored by nature had any plausible excuse for being there…. We suspect that the best equipment for an intelligent woman is a full-length mirror in her bathroom and a smaller one in her vanity case. A bottle of perfume and a lipstick are of greater help in a woman’s hour of need than a parchment presented by some learned spinster certifying her incomparable knowledge of Middle English.”

“Though to the bilious eye of The American Spectator,” Vassar’s conspirators responded, “we may seem by the very launching of this publication to have become the prototype of desiccated womanhood, our purpose in quoting this diatribe is to refute it. We can only say that if the first issue proves a carbon copy of the male mind as shown in The American Spectator, we will welcome the inevitable speedy oblivion which will be ours. We admit that the format of that journal has been a genuine inspiration to us; for the rest, our meek anonymity has little in common with the male ego which lurks behind that list of illustrious names which bedecks The Spectator. And we hope that this intellectual venture of ours will no more disturb the all-wise purposes of Jehovah than (we trust) the literary dalliance of these gentleman has interfered with their lawful begetting of infants.

Oscar Wilde once observed that alcohol, if taken in sufficient quantities, produces all the symptoms of intoxication. On the same principle, we have observed that education, if absorbed in sufficient doses, produces all the symptoms of intelligence in women. But we still suspect that the best equipment for an intelligent woman is a full-length mirror in her bathroom and a smaller one in her vanity case. A bottle of Chanel’s and a Guerlain lipstick are of greater help in a woman’s hour of need than a parchment presented by some learned spinster certifying her incomparable knowledge of Middle English.

Here, as elsewhere, the women defended their intelligence while mocking the conventions of Vassar—represented, they claimed, by The Vassar Review—in order to claim an autonomous literary authority. They did “not wish to exude the spirit of the classroom,” and, they observed, “as far as we can see, the editorial policy of the Review seems to be something like this: ‘The Review cannot publish any forward-looking writing, because it aims to represent the majority of the college. And, of course, in an aristocratic college like this there are only a few forward-looking people.’”

While the faculty weighed the new publication’s merits, students weighed in, sharply criticizing the new journal in The Miscellany News for March 11, 1933. “L. P., ’34” (probably Louise Paskus) understood “the editorial policy of anonymity,” saying one “can at least understand the desire of some of the contributors to remain anonymous. This applies particularly to the poets. Unintelligibility should not be a standard of excellence for poetry.” Finding the prose “far better and more authentic,” she hoped “that in the next issue the ‘lack of finish’ which the board is willing to overlook will not again take the form of undue obscurity.”

“H.D.R., ’33” (probably Helen Ratnoff) claimed her “sour reflections” on Con Spirito, were “not a plea for monotony,” but rather “merely a request for clearer statement of aims and methods. What does Con Spirito represent? Is it a cry of thwarted souls who have not found an outlet for their strivings or is it a sincere expression of a felt need? That question could best be answered by the editorial but it is precisely there that no answer can be found. For the prevailing impression—besides the anonymity—is incoherence. What is the connection between Chanel and fresh conception?”

“J. F. T., ’35” (probably Jean Tatlock) also took exception to the first issue’s editorial—not to its subject, to its tone. “The editorial,” she wrote: “seems over-adequate in expressing the negative purposes of the sheet: the defence of woman’s intellectualism, the revolt against the ‘academic stamp:’ what it implies are the political and therefore spiritual limitations of the Review…. It leans toward the American Spectator in glibness and mockery out of keeping with itself, why not the substance without the distractingly clever digs?” She concluded her précis in temporation: “After later appearances, it will be more to the point to try evaluation, to temper enthusiasm with backing, or disapproval with crushingness.”

All of the new publication’s founders except Eleanor Clark were on the Misc. staff, and her sister Eunice was the editor-in-chief. The editorial in the March 11 issue attempted to moderate “the storm of epithets that has fallen on the heads of Con Spirito’s mysterious editors.” Describing themselves as “newspaper women…bound up…inextricably with transient and worldly issues” and disavowing “setting ourselves up as literary critics,” the Misc. editors responded to criticism of Con Spirito’s anonymity:

In a college where most people take their education as justification for needless tearing down and a jeering attitude toward all attempts at building anything…we refuse to allow the basic considering in our judgment to be the question of anonymity…the essential point about this queer little new publication is not whether it’s anonymous but that it is at all…. At least there are some people in college with guts enough to get it out, and that not for any personal glory but out of the pure joy of doing something…. If Con Spirito were the work of Edgar Guest cooperating with the devil himself, it would be a relief to have literature competing with Junior Prom as one of the eternal subjects worthy of our dinner table conversations (along with such enlivening topics as men, food, and clothes).

By early May, student comment in the Misc. took on an air of levity. The May 3 issue carried a letter signed Cum Grano Salis:

May we thank the Editors of Con Spirito through the columns of The Miscellany News? They have given us a sudden realization of our own powers. One night, feeling the effects of a wholesome tombstone pudding, we embarked light-heartedly on an undertaking whose import we could not glimpse. One of us supplied adjectives, another nouns, a third—well, when we admitted them, verbs; the typewriter sneaked in and idea or two. We sent the results to Con Spirito! And behold! We’re among the immortals!

Thank you, dear Con Spirito, for believing in us! We came to scoff and remained to pray.”

Among several English department members interviewed by The Miscellany News about the publication in May, Professor Helen Sandison said, “It is fine to see a group of people with something to say…Con Spirito is new and fresh, and has therefore more vigor and impetus than The Review, although the best writing in each is on the same level. The Review, being a quarterly, has that mark of an exercise which will always strike an established periodical but from which Con Spirito is still entirely free. There is need for a publication just as long as there are any people writing with something to express.

Professor Alan Porter, a former editor of the British journal, Oxford Poetry, commented,

Con Spirito has the cleverer verse of the two, but it is a bit too mischievous and self-conscious…. The Review has a lot of good stuff in it, but it is somber and rather pompous, and the cover looks too wintry. However, I should like to have The Review remain good children and semi-official, while Con Spirito should remain bad children and not at all official. I think a combination would be poisonous.” And another of McCarthy’s mentors, Professor Anna Kitchel, observed, “While Con Spirito has the advantage of being an innovation, the stability of The Review should be recognized.

Publishing a wide variety articles—from political commentaries to reviews of campus events, fiction and poetry—Con Spirito inspired students as an honest expression of creative, intellectual engagement and encouraged experimentation. Although there was support for them among certain members of the faculty and the student body, most of the published work was by the editors themselves.

According to Bethany Hicok, author of Degrees of Freedom: American Women Poets and the Women’s College, 1905–1955, “A reading of the three issues of Con Spirito reveals not only high-quality writing, but also a critical edginess that places these women at the forefront of the literary and political debates of the 1930’s.” Notably, they treated these debates sardonically. In their second issue, published in April of 1933, Mary McCarthy wrote a piece on fascist leaders in which she exclaimed, “Mussolini looks like a bull…. Hitler looks like a shoe salesman and gets drunk in the Hofbrau at Munich…. The Vatican doors open and the Pope steps out. But the Pope is an ex-mountain climber of seventy-odd, who composes new encyclicals on birth-control, and sets new red hats on his prelates’ bald heads, while the Italians increase and multiply as the Lord commanded them, and the Nazis, Poland looking, test their clubs on Communist pates.”

In other articles, they parodied their academic experiences at Vassar. “The Bacchae, or Reveling Women,” melds D.H Lawrence with Euripides’ The Bacchae, through a character named Dionysus H. Lawrence, who begins the “play” by declaring,

Here come I now to England’s stately shore,

Forged in the dirty deeply dug-down mines.

My father was a handy man of toil

My mother—for details see Sons and Lovers.

Leaving the sordid town of Nottingham

And carrying this sweetly Phallic Symbol,

Symbol of the pure and lovely life,–

But ho! Is not my revel-band approaching,

Lovely ladies stepping in the polka?

Most of the verse in Con Spirito was probably composed by Bishop, the poet of the group. “Bishop’s theory of poetry,” Bethany Hicok posits, “can be seen very much in the context of the overall project of Con Spirito and its improvisational nature.” She published four poems and two stories in the literary newspaper’s two issues.

Among those works that eventually found their way into The Complete Poems 1927–1979 (1979) was the third of her ”Three Sonnets for the Eyes”:

Thy senses are too different to please me –

Touch I might touch; whole the split difference

On twenty finger´s tips. But hearing´s thence

Long leagues of thee, where wildernesses increase… See

Flesh-forests, nerve-veined, pain-star-blossom full,

Trackless to where trembles th´ears´eremite.

And where from there a stranger turns to sight?

Thine eyes nest, say, soft shining birds in the skull?

Either above thee or thy gravestone´s graven angel

Eyes I´ll stand and stare. The secret´s in the forehead

(Rather the structure´s gap) once you are dead.

They leave that way together, no more strange. I’ll

Look in lost upon those neatest nests of bone

Where steel-coiled springs have lashed out, fly-wheels flown.

Con Spirito was relatively short lived—published for the first time in McCarthy’s senior year, it did not have much time to develop before its founders began to graduate. In the third and final issue, published in May of 1933, the editors explained,

Because most undergraduates are more shy of their own selves than of someone else’s idea of them, we have not yet found in the college enough honest writing to justify the existence of Con Spirito, and we have printed a few outside contributions. This does not affect our belief in the possibilities of college talent; that is what we are looking for primarily, and sooner or later we expect it to take off its campus make-up and look itself in the face.

Elizabeth Bishop offered a more pragmatic reason for Con Spirito’s cessation. “Most of us,” she told poet Elizabeth Spires ’74 in 1981, “had submitted things to The Vassar Review and they’d been turned down. It was very old-fashioned then. We were all rather put out because we thought we were good. So we thought, Well, we’ll start our own magazine. We thought it would be nice to have it anonymous, which it was. After its third issue The Vassar Review came around and a couple of our editors became editors on it and then they published things by us.”

An anonymous poem “Epithalamium,” in The Miscellany News for November 29, 1933, celebrated the conspirators’ accomplishment with something of Con Spirito’s flair:

Hymen, Hymen, Hymenaeus

Twice the brains and half the spaeus…

Con Spirito and the Review

Think one can live as cheap as two…

Literature had reached a deadlock,

Settled now by holy wedlock,

And sterility is fled,

Bless the happy marriage bed.

Con Spirito successfully called into question the established academic, political and jounalistic conventions and caused ripples in the Vassar community. All of its editors went on to publish in The Vassar Review, and in later years, Mary McCarthy and Elizabeth Bishop both submitted material from Con Spirito to prospective publishers as a sampling of their work. “It is clear,” Bethany Hicock writes, “that Con Spirito was viewed by its writers as a launching pad of sorts to literary careers.”

The editors of Con Spirito shared a vision of literature as having the potential to be revolutionary, which defined their paper as well as the careers they later pursued. McCarthy is most famous for her 1983 The Group, which is roughly autobiographical and includes fictionalized accounts of the lives of her Vassar classmates. She was variously a novelist, memoirist, travel writer and political activist. Con Spirito contains the seeds of the style and content of McCarthy’s later work; throughout her career, she was unreserved and unsparing in her portraits of her world.

Bishop’s poetry, in which she found new forms and rhythms, was an integral part of the modernist movement in literature. She served as Poet Laureate of the United States, and her poems won both a Pulitzer Prize (1956) and a National Book Award (1969). Frani Blough did not pursue a literary career after Vassar, nor did Eunice Clark, but Blough and Bishop remained life-long friends, maintaining a prolific correspondence. Eleanor Clark later gained acclaim for a range of literary pursuits, including literary criticism, short stories and novels. During and subsequent to her college career she was, according her obituary in The New York Times, “a conspicuous part of the city’s intellectual left, writing for The Partisan Review, The New Republic and The Nation. She was viewed as independent minded with a youthful social conscience.” Married in 1952 to poet, critic and Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Robert Penn Warren, she won the National Book Award for her 1965 non-fiction work, The Oysters of Locmariaquer, a work that inventively combined careful scholarship with travel writing and fiction.

Con Spirito commemorates a literary collaboration it fostered between a group of women whose relationships with one another may be intimately connected to their subsequent influence on 20th century American literature. And, as Elizabeth Bishop told Elizabeth Spires, “…we had a wonderful time doing it.”

Related Articles

Informal Interview with Mary McCarthy

Sources

Katherine H. Adams, A group of their own: college writing courses and American womenwriters. 2001.

Bethany Hicok, Degrees of freedom: American Women poets and the women’s college, 1905–1955. 2008.

Mary McCarthy, How I Grew, 1987.

Brett C. Miller, Elizabeth Bishop: Life and the Memory of It, 1995.

“Editorial,” The American Spectator, Volume I, No. 1, January, 1933.

“Con Spirito.” The Miscellany News. Volume XVII, February 8, 1933.

“Public Opinion.” The Miscellany News. Volume XVII, May 3 1933.

“Con Spirito.” The Miscellany News. Volume XVII, March 11, 1933.

“Public Opinion,” The Miscellany News, Volume XVII, March 11, 1933.

“To the Editors of The Miscellany News, The Miscellany News, Volume XVII, March 11, 1933.

“Faculty Express Varied Opinions on Publications.” The Miscellany News. Volume XVIII, May 6, 1933.

“Epithalamium,” The Miscellany News, Volume XVIII, November 29, 1933.

Robert McG. Thomas, Jr., “Eleanore Clark is Dead at 82; A Ruminative Travel Essayist, The New York Times, February 19, 1996.

Elizabeth Spires, “Elizabeth Bishop, The Art of Poetry No. 27,” The Paris Review, No. 80, Summer 1981.

“Con Spirito,” Subject File. Vassar College Archives and Special Collections. (VCSC).

Eleanor Clark. Biographical File. VCSC.

Elizabeth A. Daniels, “Informal Interview with Mary McCarthy,” Vassar Encyclopedia https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/interviews-reflections/mary-mccarthy.html

VE, 2012