Blood and Fire

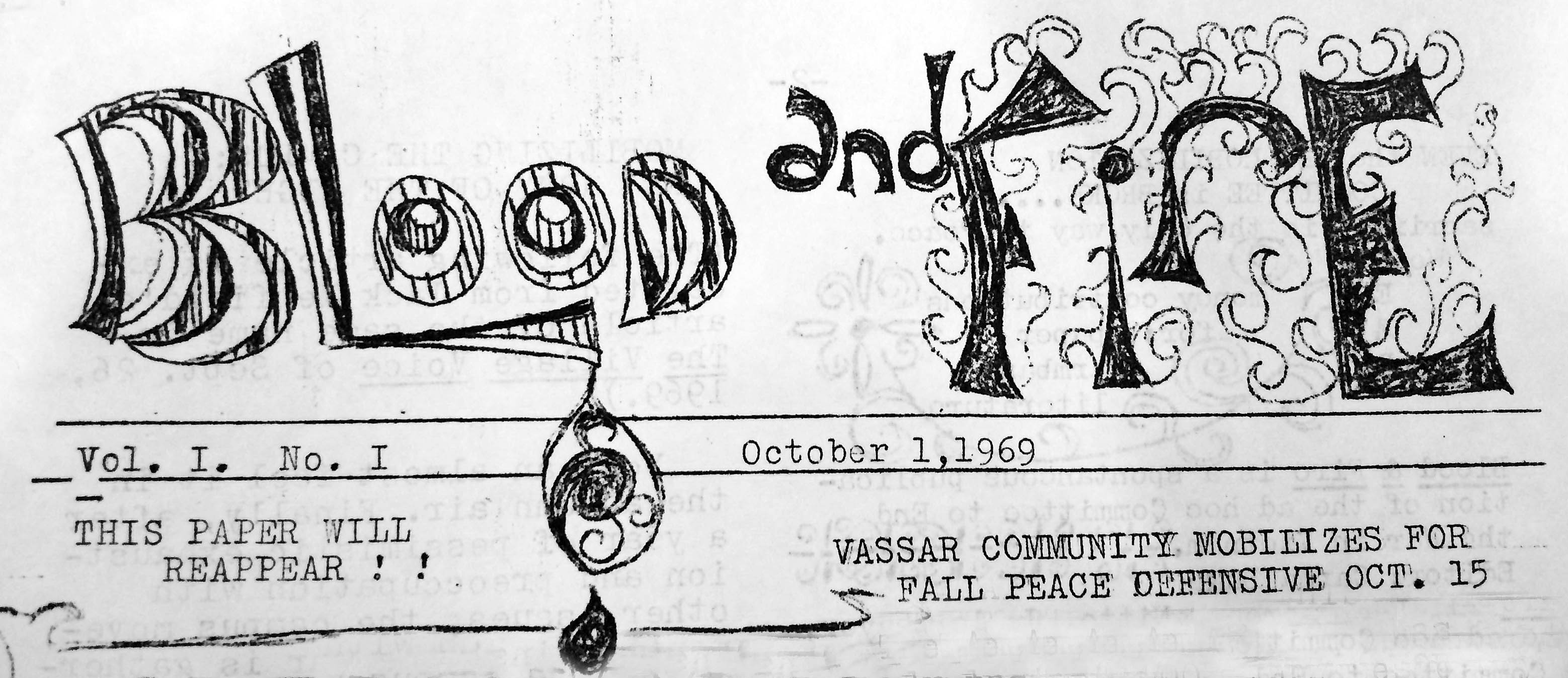

Vassar’s ad hoc Committee to End the War in Vietnam immediately embraced the moratorium. Sophomore Carla Duke ’71, along with Julie Thayer ’71 and Carolyn Lyday ’72, published four editions of a pro-moratorium “spontaneous publication,” Blood & Fire. The mimeographed two to four page issues had a small distribution, but they embodied the fervor and nature of on-campus antiwar sentiments. Written in the bold, evocative style adopted by many protestors, Blood & Fire demanded the attention of the student body, implicated them in the Southeast Asian morass and confronted Vassar students with a haunting question: “who will be left to celebrate the victory of blood and fire?”

The paper’s name references Joseph Stalin’s response to the Yugoslav politician Milovan Djilas’s condemnation of the Red Army’s unprecedented aggression in Yugoslavia. Stalin declared: “Does Djilas, who is himself a writer, not know what human suffering and the human heart are? Can’t he understand it if a soldier who has crossed thousands of kilometers through blood and fire and death has fun with a woman or takes some trifle?” Duke, Thayer and Lyday deftly transferred these callous words from a Communist to an American context, thus eliminating from the outset any room for equivocation in their publication. Their masthead declared that the war in Vietnam was unjust, a destructive conflict of blood and fire and a replication of Communist brutalities rather than a bulwark against them.

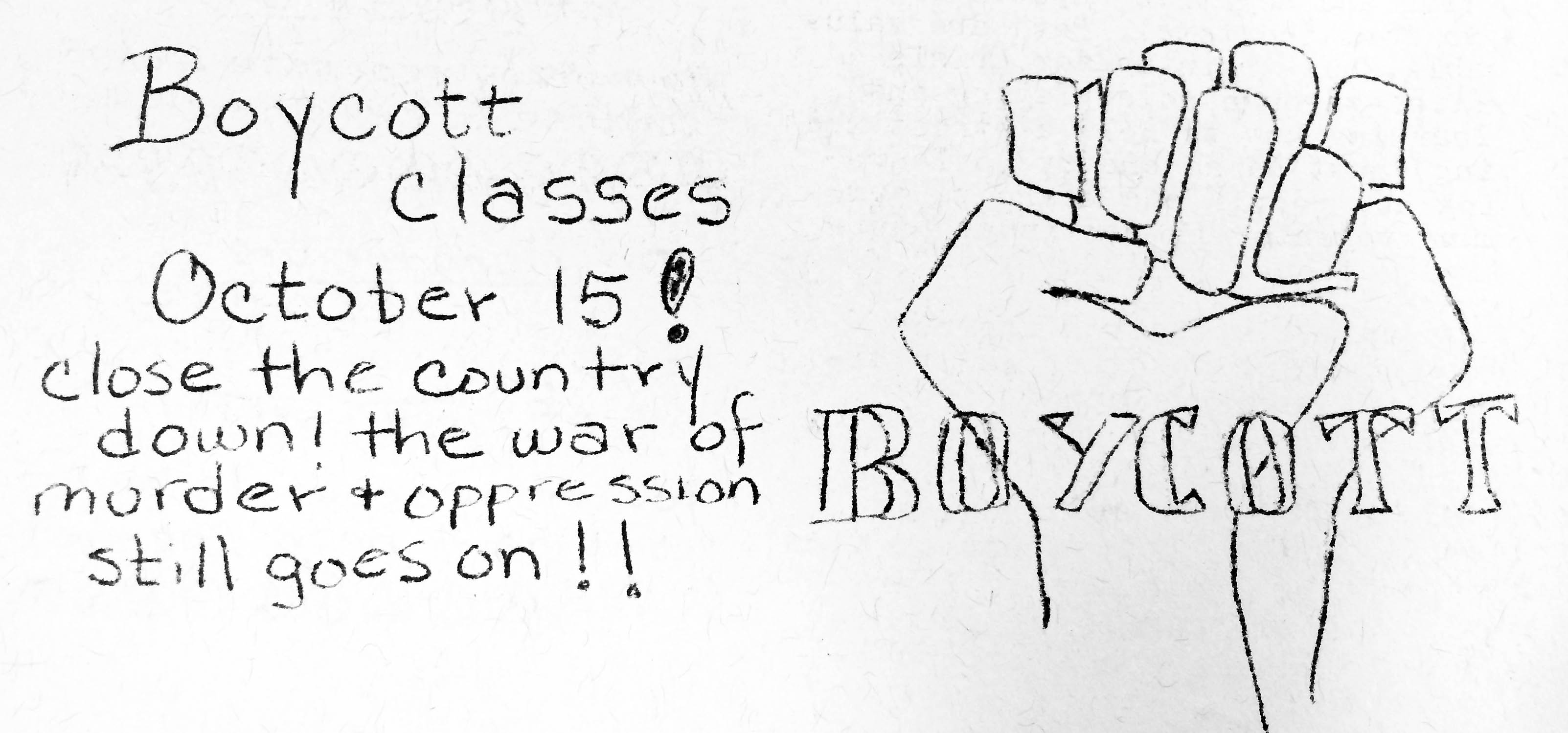

The editorial board circulated its first two issues in the lead-up to October 15 and the moratorium. Distributed on the morning of October 1, the first issue heavily advertised the moratorium, encouraging student participation and printing the results of the pro-moratorium “petition count” to be presented to President Alan Simpson. As of the first of the month, 152 professors and over 920 students had signed the petition. The issue also featured Carolyn Lyday’s response to the allegation by College of New Rochelle political scientist Robert Markle that only a “minority of radical students and faculty found on all college campuses,” a disruptive, “fringe political movement,” supported the moratorium. She countered:

“We are rather a majority of college students and faculty who are together organizing, not ‘disruptions of the public and private educational process,’ but an extension of that process. A ‘holiday from classes’ is exactly what we don’t want; rather, to focus the day’s studies on an urgent national issue, and to bring this educational process into the surrounding community….

We believe in democracy, and also in not infringing on the civil rights of any individual. It was not necessary to force anyone to sign the petition asking the Administration to join us in this educational venture for peace.”

This issue also briefly discussed the recent Fort Dix controversy. On June 5, 1969, U.S. military deserters imprisoned in the stockade rioted against overcrowding, maltreatment and the unsanitary conditions they endured at the Fort Dix Stockade by hurling their bunks from the barracks, threatening to start fires and menacing the guards. Thirty-eight of the 200 rioters—the “Fort Dix 38”—were charged with a series of crimes for their “‘political activities’ against the war” according to The Misc. The October 1 edition of Blood & Fire encouraged students to travel down to New Jersey for a demonstration on October 12 to show solidarity with the Fort Dix GIs protesting the war. On October 8, Carla Duke invited Staff Sergeant Rudy Fox to discuss the protest with Vassar students. The Miscellany News printed Fox’s argument that the upcoming demonstration represented an important step in the process of projecting a “sense of unity among students, workers, and GIs.”

Fox’s appearance and the Fort Dix controversy got lengthier coverage in the second pre-moratorium issue of Blood & Fire, printed on October 8. The edition denounced conditions in the stockade: “Fort Dix Stockade is a prime example of the human injustice of the U.S. It is one of the foulest stockades in the nation. Built to house 350 prisoners, it now bursts with over 800 due to the refusal of GI’s to participate in the Army. Over 90% of the men are there for going AWOL from ‘the green monster.’”

The remainder of the issue defended conscientious objectors who were drafted for the war and advertised the moratorium heavily. In conjunction with the Draft Counseling and Information Service of Duchess County and its campus liaison, history professor David Schalk, the editorial board listed resources for Vassar’s newly-welcomed male students who opposed the draft. It also listed the activities taking place on October 15 in lieu of classes.

A letter from Julie Thayer, in charge of the General Information and Contributions for the Moratorium Steering Committee, urged Vassar students and faculty members to participate in moratorium activities to “show that [Vassar] will not give tacit approval to the war in Vietnam and related actions of the United States.”

On the day of the moratorium, the board printed its third issue replete with an account of U.S. Army suppression of the October 12 demonstration at Fort Dix, Vassar student protests at nearby West Point and a pledge taken by 23 Vassar men to resist the draft. Despite the violent repression of the Fort Dix protestors and the West Point cadets’ general lack of response to the Vassar girls’ entreaties, the overall tone of the issue was that of cautious optimism undergirded by calls for continuing vigilance. The moratorium turned out to be a rousing success, and the editorial board praised it as a powerful display of unity against “the war co.,” maintaining, however, its emphasis of the importance of continuing antiwar activism. Highlighted phrases such as “peace and freedom rising” and “THE WAR STILL GOES ON! ! ! !” capture the dual message of Blood & Fire’s third issue.

The journal’s final issue appeared almost a month after the moratorium. Circulated on November 13, this edition continued to print information about upcoming protests on campus, in Washington D.C., and in Dutchess County, but it also took on a more general quality. It printed the agenda of the national New Mobilization Committee to End the War, formed in July 1969, which declared that it would not be “deflected from its aims by the deceptive ‘peace’ plans of the Nixon administration” nor rest until “the U.S. renounces all military pacts to defend corrupt and dictatorial governments.” Another op-ed by liberal journalist and author Nicholas von Hoffman mused about the unjust depiction of antiwar sympathizers and reiterated the position of the national antiwar movement:

“The double-mouthed critic who wants to have a leg on both side… likes to say: Your cause is noble, and public spirited, but some of your leaders and/or followers are Communists, radicals, activists, and lunatics. There is a degree of seeming possibility to this. Some of us are jarred when we learn there are 2 Communist party members on the local peace board. But the point is that there is no way to bar Commies or SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] members: The peace movement is a movement and not a political party.”

This shift from the specific, incident driven content focus of the first issues to the more general, ideological focus of this last issue might be accounted for by President Nixon’s conciliatory “Address to the Nation on the War in Vietnam” broadcast on November 3, 1969. In his speech, Nixon continually asserted that his plan of Vietnamization (gradual withdrawal) “will end the war and serve the cause of peace—not just in Vietnam but in the Pacific and the world.”

In an effort to maintain active, outraged opposition to the war at Vassar, Blood & Fire’s editorial board harshly called Vietnamization a synonym for “indefinitely prolonged Amer. involvement in the war,” rather than a policy of gradual withdrawal, adding: “The true way to Vietnamize the war is to withdraw completely the U.S. forces that Americanized it in the first place.” This reiteration of the repeated call of the Committee to End the War for immediate, unconditional withdrawal reflects an anxiety about keeping the on-campus antiwar war cry strong and prominent as Nixon amped up his rhetoric and appeals to the American public. The handwritten phrase “making war for peace is like fucking for chastity,” scrawled like on emblem on the final sheet of Blood & Fire’s final issue neatly summarizes the editorial board’s continuing call to antiwar action and condemnation of Vietnamization.

It is difficult to quantify the impact of this publication. The Committee to End the War advertised the moratorium through numerous other channels and Blood & Fire received no contemporary mention in The Miscellany News or The Vassar Chronicle. Many students continued to support the war and likely had little interaction with the left-wing publication. Yet its influence, demonstrated by the resounding success of the moratorium on campus and in Poughkeepsie, is clear. On October 15, nearly 5000 protestors from Vassar, Duchess County and surrounding colleges attended the antiwar rally held at Poughkeepsie’s Riverside Park to voice their discontent with the war of blood & fire.

Related Articles

Vassar during the war in Viet Nam

Sources

Dijlas, Milovan. Conversations with Stalin. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1962.

Rosenbaum, David E. “How Moratorium Grew into Nationwide Protest,” The New York Times, 12 Oct. 1969.

Cruz, Jon. “Vassar experiences the Vietnam War,” The Vassar Chronicle, 18 Apr. 2003.

Casteras, Susan. “Moratorium and the Town 4000 March to Riverview,” The Miscellany News, 17 Oct. 1969.

Shaffer, Kelly. “GI’s Demonstrate; Protest Suppression,” The Miscellany News, 17 Oct.1969.

“Bringing Feminism to Vassar,” The Miscellany News, 4 May 1973.

Blood & Fire, October 1, 1969. Dated Materials on Strikes and Protests re: Vietnam 1967- Nov. 1969, Folder 1.7. Vassar College Special Collections (VCSC).

Blood & Fire, October 8, 1969. Dated Materials on Strikes and Protests re: Vietnam 1967- Nov. 1969, Folder 1.7. VCSC.

Blood & Fire, October 15, 1969. Dated Materials on Strikes and Protests re: Vietnam 1967- Nov. 1969, Folder 1.7. VCSC.

Blood & Fire, November 13, 1969. Dated Materials on Strikes and Protests re: Vietnam 1967- Nov. 1969, Folder 1.7. VCSC.

General Material on Vassar and Vietnam, Folder 1.1. VCSC.

Nixon, Richard. “Address to the Nation on the War in Vietnam,” November 3, 1969. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=8237.

CG, 2015