Informal Interview with Maisry MacCracken ’1931

The daughter of Henry Noble MacCracken, Vassar‘s president from 1915 to 1946, Maisry MacCracken graduated with the Vassar Class of 1931. This interview by Maya Peraza-Baker ’08 was conducted on September 11th, 2006.

MPB: One of the most interesting things, to me, is that you grew up at Vassar didn’t you?

MM: I did.

MPB: Do you have any anecdotes about growing up at a women’s college and what it was like, being the daughter of the president?

MM: Well, I used to ride my velocipede around the college. I even rode it around in summertime through the corridors of Main Building and I learned to ride a bicycle there, and used that a lot. I also played with various children of faculty who lived in the houses across the street from the college. My brother used to sleep on an outdoor porch in the president’s house and he’d tie a string on his toe to a cage that would catch a bird during the night. Then he’d go down and band the bird, having been taught by a student, who later became president of Radcliffe College.

I also remember a group of students who took me—I was probably 7, 8, or 9 (that kind of age)—to the Mohonk Mountain House. We didn’t go in the Mountain House; we went up to the top of the mountain it faces. I remember that very well, trying to keep up with the students. We went by streetcar, which we got at Taylor Hall (at the gate), it took us right down Main Street, to the ferry landing that took us across to Highland. I think there was a trolley there that took us a little way. I don’t remember much of the walk from there, but I do remember climbing the mountain and getting to the peak of it at Mohonk.

MPB: Now, I know that both of your parents were very involved in the Poughkeepsie Community, and that they founded the Lincoln Center?

MM: Yes.

MPB: What can you tell me about that? Did you have an involvement with the center?

MM: No, mother used to try and get us to come down to the center with her, but we never did. She had helped found it with Professor [Laura] Wiley, I think it was, and a group of students who opened a store on lower Main Street. There was a boy’s school [Riverview Academy] that had closed and they took over those buildings. It was on Lincoln Avenue because, at that time, most of the poverty in Poughkeepsie was between Lincoln Ave. and the Waterfront. Things have changed now and most of [the poverty in Poughkeepsie] is [between] Pershing Avenue and North Side. I remember, when I was a librarian at Dutchess Community College, I was at the circulation desk working with a black woman who told me that she had grown up at Lincoln Center and was very, very grateful for it. She remembered mother and the Vassar students who used to come down and lead classes in handiwork or athletics or things at the center.

MPB: Because you graduated with the class of ’31, you were a student while your father was president. How was that?

MM: Well I lived primarily in Lathrop, and then Main building senior year. I remember, as a freshman, I had Miss [Helen] Lockwood, and the fact that my father was president woffuld have made no difference whatsoever in what she required of me. She was a demanding teacher and very good—I loved her class. I was a history major, and I never felt that it made any difference to any of my professors [that my father was President]. I didn’t go home often, partly because I was busy, but partly because I didn’t want to seem to be taking advantage of it. My mother had an at home every Thursday where she served tea to any students or professors who would come in. I sometimes went to that if I had something special to report, or to ask about [my siblings].

MPB: Now I know you became a librarian after graduating.

MM: Yes.

MPB: What made you choose being a librarian?

MM: Well, there was a family orientation was toward teaching, but I was a shy person. I didn’t know whether I’d have the courage to face a class every day. I felt safer. I was also interested in using the Vassar Library, that is, doing research there. I had had a class with Ms. Texter on the history of the Balkans. We used to call her Ms. Textless because she wouldn’t allow any of us to use any encyclopedias. She made us get as much first hand information as we could, and this meant doing a lot of exploring at Vassar. I found that I enjoyed it very much, so I thought doing that kind of research, and being a librarian, would be an interesting life.

MPB: I know that over lunch you mentioned your foster sister [Christine Vassar Tall]. When did she become your foster sister?

MM: Well her mother (1) [contacted] the college in 1941, when England was under threat of an invasion by the Germans and London was being bombed. Children were being sent by their parents to the countryside or overseas. Her mother asked if anyone would take care of her daughter if she was able to sent her to the United States. My father heard about it and, after consultation, he invited Christine to come to our home, and she came. I think she was about 13 at the time, and by then I was no longer at home; I was working. I met her at Christmas and summer vacations. She went to Arlington High School and was in the Vassar class of 1947.

MPB: Betty Daniels told me that your father started something like 31 organizations in his time. Do you much about his founding all of those organizations? I know that he made a lot of changes at Vassar.

MM: Well I remember when I was very little, going with him down where Raymond Avenue meets Main Street. Around the corner was a firehouse, and up the stairs they had a clinic where mothers could bring their babies for examination. I remember that that was early on, and it was part of his interest of in the health of the county. I believe he founded the Dutchess County Health Organization in 1916. Another thing he did, early on, was to have an athletic exhibition—races, high jumping and all that kind of thing—with young people from all over the county. I remember that that went on for several years. I was so little at the time when we came that I really didn’t appreciate what he was doing. I’ve been so glad to read Betty Daniels’s book, which explains a lot of the things that I knew or was told later—if not in the same detail that she writes.

I’ve often wondered how my father ever financed at that time. Faculty salaries were very low, but my father financed education for me, for my sister, my brother, my adopted brother, Christine, and a cousin who graduated class of 1940. I even know of one girl who was very brilliant but, in the depression, her family couldn’t finance the cost of both the tuition and the room and board. My father invited her to come live in the president’s house, and she boarded there. She was able to go to college and worked while she did it. He did so many things, in and out of the college, but he also looked after us kids. He didn’t lose sight of that. And that, looking back on it, amazes me. I wish I could have told him how amazed I was but I didn’t think of it at the time.

MPB: Also, I know that you’re father was involved in the theater at Vassar.

MM: Yes, he loved it as a way to get to know students, and he was always very dramatic in what he did. He just loved the theater. I know one story he used to tell about when he was acting in a play in Greek under Hallie Flanagan. He was supposed to be some leader and he had had his secretary get him a pair of sandals. When he was rehearsing he would forget his lines in Greek and he’d turn up his toes in the sandals, trying to remember. Then, Hallie Flanagan would shout, “Prexy! Put your toes down!” This would make him forget his lines again and in trying to remember, the toes would turn up again. Finally, Hallie said, “You’ve got to wear shoes to the performance.”

MPB: Over lunch, you mentioned a sculpture that was made of your father.

MM: Yes, the sculpture of his head carved out of stone. It was by Korczak Ziolkowski, who created a statue of an Indian on horseback in the Grand Tetons out in Wyoming. (2)

MPB: If you could just tell the story about the sculpture again, because now we have the recorder.

MM: He did it because of something my father had done for him, and it was a way for expressing gratitude. But mother didn’t like it; she called [the sculpture] “Prexy on the Half-Shell.” When they retired they took their other things with them but left that in the basement of the president’s house. It got from there to the basement of the building that is now the home of the Film and Drama departments. [Recently, it] was wanted for an exhibition of Ziolkowski’s work. So, we (as a family) gave Vassar title to it, to do whatever they wanted with it.

MPB: I know that you came back for the reunion this summer. How was that in terms of visiting Vassar and being the only representative of your class there?

MM: The alumni association was wonderful to me. They underwrote my visit so I only had to pay for transportation and they got me around in a bus, with the class of 1936, which was also reuniting at the time. It was interesting, I have lived close to the college in my retirement years—with my sister—so I have seen the growth of the college, and I have been to reunions in earlier years. But I enjoyed reunion very much. Especially because I admired so much of what Frances Ferguson did as president of the college. She beautified the buildings and, from what I’d heard talking to students and faculty, I admire her development of the curriculum during those years. She really brought about, what I felt was a development of my father’s ideals for the college in a way beyond what he even dreamed of. I was very proud to be part of it.

MPB: Since, you mentioned your father’s ideals of the college, where would you say, from your point of view, he hoped to go with Vassar during his presidency?

MM: Well, one of the things I heard him express was that he felt the college was really for the students—that the administration, the faculty, the maintenance people, were all there to serve them in different ways. The main thing was helping students to write their own ticket to what they wanted to become, what they wanted to learn, which way they wanted to go—to help them grow in responsibility. When he came to Vassar, the college was in loco parentis; [it] was supposed to take care of students. He wanted that wiped out. [He felt] the students were there to take charge of their careers. He was interested in the looks of the college too. He used to walk around the campus every day at lunchtime. He could name every tree on the campus and tell you what it was. He also used to have his secretary call up and make a date so he could play tennis at noontime with one student or another who was pretty good at tennis.

MPB: When you were at Vassar I know you studied History. Are there any stories or anything you’d want to say about studying in late 1920s, or very early 1930s?

MM: Well, I can’t remember the professor’s name, but she taught the French Revolution, and I remember that she named each of us as part of the French Revolution—the king, the leaders of the revolution, etc.). I remember I was the Marquis de Lafayette. In every class we had to perform the part we were assigned and that was great fun. We had to really act it out and all that happened. That was a fun way of learning.

MPB: So, then, actually I don’t know, how long did you live on the Vassar Campus?

MM: Well, I graduated into the Depression. I took a year at Columbia University, getting my BS in Library Science, and then went to Wesleyan in Middletown, Connecticut. They had a vacancy for a year and they took two students who had just graduated. The other girl was a cataloger, and I worked more at the circulation desk. I became interested in the small libraries in Dutchess County. I had heard reports of other places getting a bookmobile and servicing the outer areas where they couldn’t afford many books. My father got me a grant to come to Vassar for a master’s degree to study of the libraries of Dutchess County and write up a presentation about what a bookmobile could do for them. So, that’s what I did. I got my masters in 1935, still in the depression, and went into a business library after that, the only position I could get. I forget the name of the society that gave me the grant in Poughkeepsie, but I lived there and wrote a book, which they published.

MPB: At that point, living in Poughkeepsie, were you living at Vassar?

MM: I was living in the President’s house at Vassar.

MPB: I know that then you lived in a different house—was it on campus or was it on Raymond Avenue?

MM: That was many years later, when my sister and I had retired. My parents had bought a big old house on 376 that was practically backing up onto the south end of the campus. I actually left a job in Michigan to come home and look after my parents in that retirement home. I lived with them and had gotten a job at Dutchess Community College. After that, my sister and I felt we had a choice as to whether or not to fix up that big house, because it needed a lot of fixing. Instead we sold it and used the money to build a new house on that road. Behind the big house we built a smaller one and lived there. It was very close to the college, which made it possible for us to visit there frequently.

MPB: I know that you grew up at Vassar, and then you ended up coming back, are there any thoughts on the changes after all these years—between, your father’s presidency and now Fran Ferguson’s presidency just ending?

MM: Well, where the college is now, on the other side of Hooker Avenue where Raymond Avenue dead-ends, the college had had a farm, and my father used to take us there. We went walking there to visit the horses, the cows, to see the bulls and the chickens and the pigs. Where [Buildings and Grounds] is now, there used to be an asparagus field. At the corner, where there are a lot of faculty housing, there was the farmer’s house. In later years, in our retirement years, my sister and I had a garden where those chickens used to be, on the Vassar Farm that’s east of Hooker Avenue. We went there many times from our house and worked in the vegetable garden.

MPB: We have only a few minutes left. I don’t know if there is anything you’d like to talk about that I just haven’t asked about…

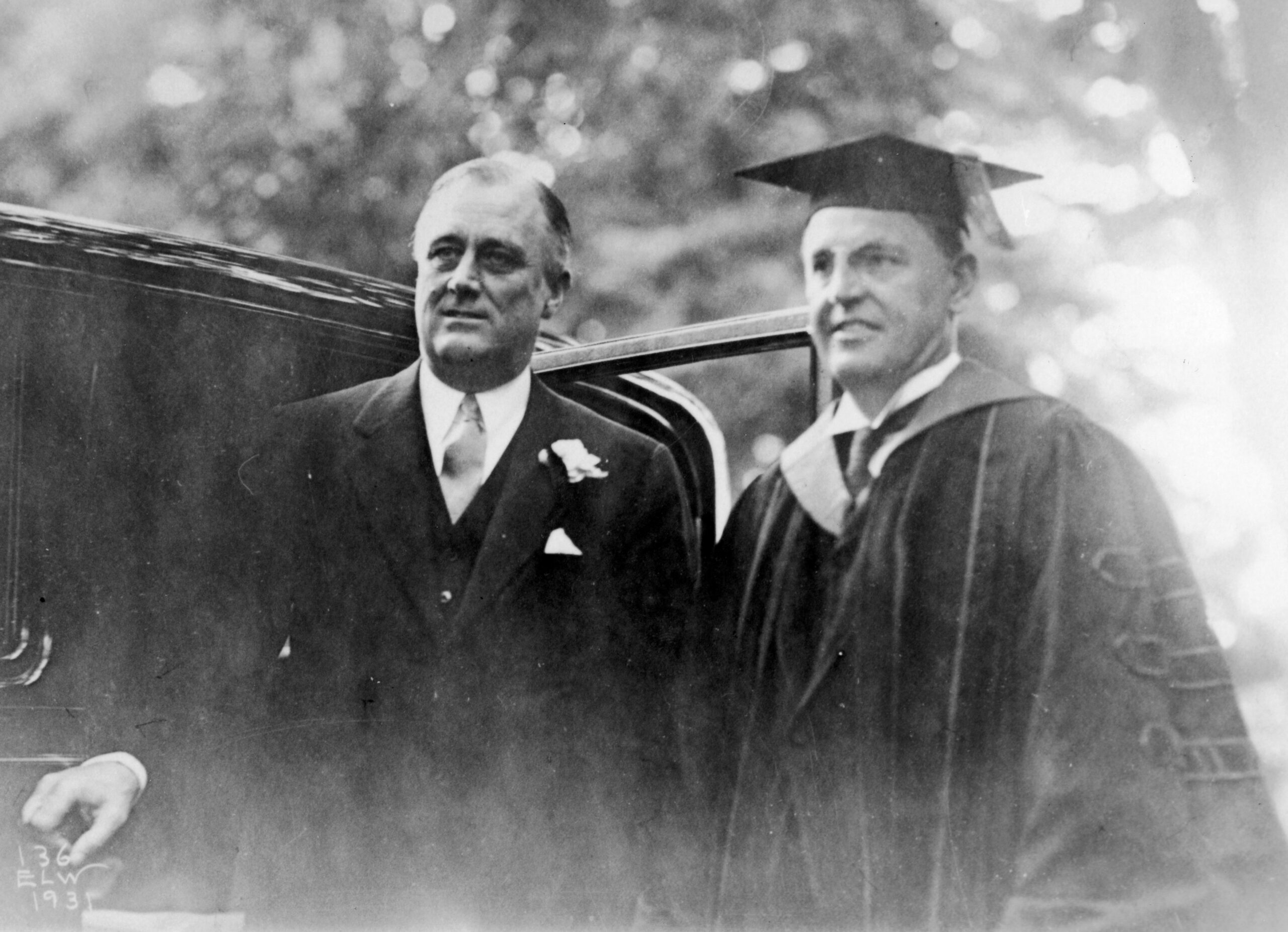

MM: Well, when I was studying for the master’s degree, my father had gotten Franklin Roosevelt to be a trustee of Vassar. He had given the talk at commencement when I graduated in 1931, when he was governor. He ran for president in 1932 and told the county that if he was elected he would make some way of recognizing them. After his election, he asked my father if he could speak from the front porch of our house because there was plenty of space for families from all over the county to come. Many people came since the entire county was invited.

After the speech he was helped into our front hall and sat in a high sofa. People formed lines to come in and shake his hand. My siblings and I went upstairs with a few friends and watched as Dutchess County came through our living room. Of course, Dutchess County was heavily Republican, and very few of those who went through had voted for him. Eleanor Roosevelt was busy talking to them, you know, bringing in farmers and their wives who were shy to shake the hand of the president, making them comfortable to do it, helping the line along. When one of our mothers came upstairs she’d taken off her right hand glove and said she was going to put it in a special box as a keepsake, having shaken the hand of a president. We said, “Yes, we saw you go through that line twice.” Of course she hadn’t but that was to tease her. We loved it. That was a long afternoon because there were so many people to go through the house. They came in the front door and went out the back. The secret service men were there to help the president get to his car when the last people had gone through because he had polio and couldn’t walk, but he never wanted it to be known. He used leg braces and did all kinds of things to keep from people seeing his legs.

MPB: Thank you so much for speaking with me today and answering my questions. it’s been very good.

Footnotes

- Christine Tall’s father, Walter Vassar, was a distant relative of Matthew Vassar.

- Korczak Ziolkowski (1908–82) undertook the massive Crazy Horse Memorial in 1939 after assisting Gutzon Borglum with the Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Although he planned the work for the Tetons in Wyoming, the project was moved to the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota at the insistence of the Lakota chiefs who had conceived it. Begun in 1948 and still in progress, the completed work is to be 563 feet high and 641 feet long.

Related Articles

- Henry Noble MacCracken

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Local Trustee

- Christine Vassar Tall: The Story of One British Evacuee

- Lincoln Center

- “Prexy on the Half-Shell”

MPB 2006