Interview with Elizabeth Moffatt Drouilhet

Introduction

Elizabeth Moffat Drouilhet was a member of the Vassar Class of 1930. She served as Acting Warden of the College from 1940–1941 and was appointed Warden in 1941. She retired from the post in 1976. She returned briefly to assist Acting Dean of the Faculty Elizabeth Daniels during a crisis in the late 1970s. She died on December 6th, 1984. The Warden was responsible for regulating students’ social life under parietal rules as well as the duties discharged today by the Office of Residential Life.

Part I: January 19, 1981

Today is January 19, 1981, this is Elizabeth Daniels and I am talking this morning with Elizabeth Moffatt Drouilhet who graduated from Vassar in 1930, who came back as acting Warden in 1940 and who was made Warden of the College in 1941 and retired in 1976. I am going to be talking to Mrs. Drouilhet about various things but I would like to start with some of her recollections about her college years proper and I would love to begin by asking her how she happened to come to Vassar in the first place? Where did you go to school? Did you have relatives who had come to Vassar? What were your reasons for choosing Vassar as a College, Betty?

I went to the Shipley School in Bryn Mawr, which was a preparatory school for Bryn Mawr College. I was not terribly interested in the thought of going to Bryn Mawr. I had lived too close to it for too many years and I think the thing that finally tipped the scales was that the Bryn Mawr cheers for their athletic events were in Latin, and that was too much for me to take. My aunt had graduated from Wellesley and had not enjoyed the college and discouraged me from going there. I had met two Vassar students who were counselors at a camp and was very impressed with them and with all they said about Vassar, and on the strength of that I applied. In those days unless you were registered at birth and had an alumnae parent, it was extremely difficult to get into Vassar. However, they had set aside 100 places for competitive admission and I applied for one of these and I am fortunate to say, succeeded in being admitted.

Did you come to Vassar for an interview before you applied to the College? Or as you applied?

Yes, I came to Vassar the year that I applied and it was perhaps the most fortunate thing I ever did because I discovered that the school had failed to report my junior year Bryn Mawr entrance exam scores which were a great deal higher than a few of the Shipley grades, particularly in the subjects I disliked. The particular subject I disliked was French, and it entirely changed my standing for admission to Vassar. Vera B. Thomsen was the person that interviewed me and she said “Why we don’t have that on the record?” And I said “Well, what shall I do? Can you write for the grades?” She said, “Well, you see if you can get them sent.” So eventually we did clear that up.

And you said that was probably because at the Shipley School they were eager for you to go to Bryn Mawr College.

They were very anxious for me to go to Bryn Mawr College and I was admitted to Bryn Mawr before I graduated from Shipley as were the top students in the class and I hesitated whether I should turn Bryn Mawr down before I heard from Vassar and finally decided Yes, even if it meant not going to college I would take a chance on Vassar.

Did you have a roommate your freshman year when you got here?

Yes, (laughing) it probably is one of the reasons that I got so interested in housing even as an undergraduate student.

Oh, please tell me about it!

The Class of 1930 entered in September 1926 which was a period when Vassar was increasing the number of students that lived on campus, and were closing their off-campus housing for freshmen in anticipation of the new accommodations to be made available within a year and a half by the addition of Cushing Dormitory. The result was a great many of my class were jammed into one-room doubles that from time immemorial had been used as single rooms. I roomed with a friend from Philadelphia. I did not know her very well but we decided to room together when we both were admitted. Two such different people could not be imagined. She was entirely domestic. She could not understand how anybody would want to engage in any sports and I must say my early years were devoted primarily to sports. She complained that there were hockey sticks or something around the room. The room was full of people in athletic attire which she found offensive. I remember very well she challenged me one day, she said “You couldn’t do anything useful. You couldn’t sew.” This was a Friday afternoon and I said “I can sew, and to prove it I’ll make a dress tomorrow and wear it to dinner tomorrow night!” Which I did. Well, we continued rooming together all year and there were no outbreaks. . .

May I interrupt to ask could you have done anything about it? I am thinking of your policy later on when you had got to be Warden of asking people to hold off if they didn’t like their roommates and so on, what was the policy, do you suppose, about roommates and allowing people to change at that time?

I don’t honestly know because it never occurred to us that we could make a change. We just went our own ways and… oh, shared the room, yes, but I think back in that earlier period, and I think this is probably throughout, I have heard other classmates who had similar situations… you didn’t get that upset. Sure, you didn’t do many things with your roommate if you were that different. Particularly since we had asked to room together, it never entered our head that you could do anything about it… and we survived.

Can you recall details of what your freshman year was like academically? Some of the teachers you had?

Well, with the exception of my history course, it wasn’t that different from school. In history I had Caroline Ware who believed in sending one right straight to look things up in the library. Most of the other sections of freshmen history had seventy pages to read out of a book. We were sent to discover what topic we wanted to write on in a general period. I can remember to this day, and have been thankful for it more than once, the topic I chose, and I had no reason… I guess it was because I had seen the Convocation, but I did the history of academic dress. Professionally it has stood me in good stead many a time. I enjoyed every moment of the history course. The other courses I found less interesting. We had seven requirements, five had to be taken in the freshman year, the two remaining were taken in the sophomore year.

And these were semester-long courses?

Year courses. I was not happy in my assignment in the English course. I gather that she was liked, but she certainly wasn’t by our class. It met the last scheduled period on Monday, Wednesday and Friday and as luck would have it, in that section were a group of athletes from the Class of ’30 and the Friday afternoon period you could always hear the clank of hockey sticks interrupting (laughing) the whole period. As the year wore on we didn’t carry a basketball to class, but we were all dressed and just waiting as the bell rang (laughing) to rush out with hurricane force. I don’t know what other recollections I have. We took much more for granted, that you did what you were told to do. If you were to take a certain requirement, you took it. I had come to Vassar to major in mathematics. I was perfectly certain that was what I was going to do; I was going to teach it. The experience with Miss Ware in freshman history changed me for I found that definitely more exciting. I was bored to death with math. I finished the classwork in less than half the time and nearly lost my mind (exaggerating her speech) waiting for others. I had inherited my father’s genius for mathematics, in spite of the fact that his field was English. I took no more math, which I later regretted because I should have gone through calculus, but I dropped it. I went into the social sciences.

Did you take other sciences?

Oh yes, I had a fascinating time with science. I decided that maybe what I really needed was biology and so I signed up for biology.

Was this freshman year or later on?

No, this was junior year. I put it off. After two weeks of trying to look through all those stupid microscopes and losing my mind, I went to Mildred Thompson and asked her permission to change and she said “Oh no you can’t, this is too much of a semester missed…” I said, “Miss Thompson, you know I spend all of my time in the library on history and my eyes are so worn out when I get out of those twice a week lab courses, I can’t read.” And after trying to persuade me, she finally said, “Well, all right. If the physics department will take you in physics you may switch.” So almost past the deadline for getting credit, I switched to physics, and I …

Who would have been teaching physics?

Wick. At least Wick was the one that I was under.

Miss Emily Wick?

Her name wasn’t Emily. But she was teaching photography—or light; I guess that was really second semester, the first semester was general physics. But I had had physics in school and I had done very well in it and it was easy for me and I had no difficulty with the work in physics in relation to my eyes. Then, second semester it was a course in light which involved primarily photography, but at least it has given me some realization of some of the major physical changes over the years because physics in those days was an infinitely simpler subject than it currently is.

Was physics in those days taught in the present physics lab [Sander’s Physics]?

Oh, yes, oh yes. Physics was the only laboratory building that I ever entered as an undergraduate. The first time I ever got in a chemistry building was the month before Sarah Blanding’s inauguration when Mary Sague and I used to meet over there at 7 o’clock in the morning which was the most convenient time for us to get together. She was chairman of that committee and I was vice chairman.

Did you know Henry Noble MacCracken as an undergraduate? Did you have reason to make his acquaintance?

Yes. I wouldn’t say that I knew him well as an undergraduate, but I knew him. Oh, I saw him at some of the Founder’s Days events, but I don’t recall really being in his office.

What kind of a reputation did he have with the students?

I think by and large, good. They liked him; he was Prexy. It’s almost impossible for me to sort out my undergraduate knowledge of Prexy and my subsequent administrative knowledge.

What was it like being around Vassar on a week-end when you were an undergraduate? How did you spend your time?

Athletics.

All week-end? Same athletics all week-end?

(Laughing) Well, everybody was on limited number of leaves so the bulk of the college was here every week-end and it was a period for…

Did you have week-end leaves? Or single night leaves?

Night leaves, but you could take two night leaves together. But even seniors had relatively few so that probably 90% of the college was here every week-end and all athletic competition was scheduled beginning Friday and going all day Saturday. There were lectures, concerts-but the big difference that I think between then and now was the amount of student activities; student conferences with perhaps an outside speaker, though not necessarily so. One conference I remember particularly was an intercollegiate model league assembly where each college took a country and prepared to address the subject that was of primary concern to that nation at that time in history. I remember one fascinating event, I don’t know whether to call it a lecture or demonstration, a man brought a light organ, which made no sound at all, but in playing the organ there were varying patterns of light. I found this one of the more fascinating things that I recall. I have never seen or heard of it since.

Patterns of light. . . where?

Displayed on a screen. The keyboard was very similar to an organ keyboard, it was called a light organ. Evidently the rest of the world was not as interested in it as I was (laughing).

Would the students from other colleges come and stay in the Vassar domitories… or would they stay in the Alumnae House… How was that organized?

Well, when you have got an intercollegiate conference that involved men as Model Assembly did, I don’t know where they put them up, but I think at Alumnae House—I think they had space there.

They would eat in the Hall dining rooms. Another thing that happened—Political Association was one of the really active major organizations and they used to run a series, oh four or five during the year, at noon on Saturday of Polit. luncheons. That was the first time I ever met Franklin Roosevelt—he was a speaker at a Polit luncheon. and I sat at his table.

The luncheon would be held in one hall?

In one dormitory—usually in Josselyn. The class shows, there was always a junior party put on to entertain the freshmen and a soph. party put on to entertain the freshmen in the fall… a large number of the respective classes took part. It was student-written, and student-directed. They continued, oh I guess ’til the early forties, and they were major events. The formal proms, junior prom was the most important, senior prom was less so. I guess junior prom was the first big formal dance. It is hard for me to think what other…

One other question I have about the late ’20s, can you remember which of the buildings that exists now, did not exist then? Well I know… I am trying to think how different the campus… how different would the campus have looked in the mid 1920s from the way it looks now in respect to buildings.

Quite different. To be specific, in the mid-twenties Kenyon didn’t exist, the gym was in Ely…

On the first floor of Ely?

All Ely was the gym. Blodgett didn’t exist; the present infirmary didn’t exist; the infirmary was Swift.

Did Metcalf exist?

Metcalf existed, it was there in the early ’20s.

And what was that used for?

It was the doctors’ residence and also by deeded gift a place to recuperate either after you had been in Swift, or if you were just exhausted, you could go over there as it had been given for that purpose. Pratt House existed. Pratt House was built in 1915.

Was it called Pratt House then?

No, it was called the Warden’s House. It was given by Charles Pratt in honor of his mother to house the Warden of the college, and

And was built when Jean Palmer…

… became the Warden in 1915.

And how about the science buildings? For example, where did the Psychology Department have its… do you remember—perhaps you didn’t take psychology—but do you remember where it would have had its classes at the time?

In between the New England building… and… oh, what’s the one building that has ever been torn down in Vassar history? It was next to the New England building—yes, (laughing) but what was it called?

Avery was known as the assembly hall… well, I can find the name of it, and perhaps I already know it, but I have a hard time picturing… do you remember where it was? Was it physically right in between the physics building and the New England building?

I think it was nearer the New England building, but… I think that is where it was.

But had that been torn down by the time you got here… do you remember?

I don’t think so because I think that’s where we had statistics.

[n.b. The building was Vassar Brothers’ Laboratory]

And Rockefeller Hall existed…

Oh, yes. Rockefeller…

And Taylor was here.

The addition to the library, the link between Taylor and the Library didn’t exist. The old ice house was still across the lake.

Over near where the Antolini house is now?

Yes. Skinner didn’t exist… Cushing was opened in 1928 and then the great period, perhaps the single most concentrated period of building was in the 1930-40 period when Kenyon, Blodgett, the Nursery School, Baldwin House and Skinner were built…

Can you account for the fact that all those buildings were built almost as a group—was there some particular reason why there was such a fertile building period? This was the beginning of the Depression. The 75th Anniversary was in ’39 wasn’t it?

’40.

Had they been collecting money?

I think they collected money, but some of this came in ’32, I think Helen Kenyon was Chairman of the Board then and was a tremendous builder; that period of ’28 to 1940 was a big period of building.

What did you do when you graduated from Vassar? Did you come back to Vassar for your first job after graduation? Can we talk a little bit about your life after Vassar, so to speak, and before Vassar? (laughing)

I came back to Vassar ten years after I graduated. Immediately following college I started a Master’s program at the University of Pennsylvania and with the encouragement of Professor Fite of the Political Science Department who advised me to get a Master’s and perhaps come back and teach in that department. Well, I did most of one semester’s work at Penn, did not enjoy it terribly much because of a major distraction; namely I met a young naval officer during the summer, and we became engaged during the fall and because his ship would be transferred to California early in the spring, we were married in February 1931 and I resigned from Pennsylvania. I went to the West Coast that summer and lived the life of a Navy wife, which for a non-domestic, fairly active individual, I found intolerable. I played bridge seven days a week for as much as four and five hours a day. I had a child in the spring of 1933 who was born the morning after the Long Beach earthquake as it is now referred to… (laughing)

Oh, were you in Long Beach… in that area?

Across the Harbor in San Pedro at the Naval Base. I came East that summer and on a Navy transport with my son who was about 3 months old. We rode a hurricane through the Carribean; both of us were pretty much upset when we finally landed and got to Philadelphia. My husband had been transferred to Honolulu. To cut a long story short, I did not go out to Honolulu and was subsequently divorced.

In 1935 the Depression hit all of us very hard. I knew I wanted to find a job, if one could be found—had to find a job—and I went to all the places around home because I couldn’t afford to live except at home and I had a grandmother and mother who could watch the baby while I was away. I went into Harcum Junior College one day to apply—I knew I wanted to be with older students—and said I was looking for a job in the social sciences. They thanked me very much and said they would keep my name, but they had nothing. Then a day or two later they called back and said “What did you mean by social sciences?” I said “History, economics, political science (laughing)…” and they said “Oh, we do have a job and we would be glad to have you come up for an interview.” So I went up for an interview and was hired to teach five courses, one of which was sociology, a course I had never taken (laughing) in college.

That’s probably the one you did best in! What were the others in?

Oh, World history, Elementary Economics…

I can understand that.

Oh, yes, and I also got quite interested in the extra-curricular activities, particularly the student government, or lack of it, there. It was a fascinating school. It was a private school, founded and run by Mrs. Edith Harcum who was a concert pianist in her own right and did superb work in music. Her husband had been killed in an automobile accident and she carried on. And, you can do things on a shoestring and still have some validity. I was on my own. And I was also, I soon found out, jack-of-all-trades.

Was she really the Principal of the School?

She was owner and Principal. And a remarkable and very interesting woman. The second year I taught four courses and extra time was devoted to working with student government and the student organizations. At the end of the second year I gave up all but one course, Contemporary History, which I kept as long as I was there. I became Registrar, Assistant to the President, and I don’t know how many titles. I was not Dean of the Faculty though I had a great deal to do with the hiring of the faculty; I was working out all business problems in the college. I wouldn’t have given up those five years—they made Vassar seem simple because I really learned on a small scale—there were only about 100 students, and relatively few boarding students, everything from A to Z that’s involved in operating a junior college, but there’s not that much difference.

So did someone at Vassar know what was going on… getting back to your stay?

This is again very funny because one of the things I had to do was organize the Commencement and in the spring of 1939 I invited Dr. MacCracken to be our Commencement speaker and he accepted and came down. We did have an academic procession; I not only had to run that but I had to entertain Prexy, because Mrs. Harcum was going to play [the piano] that afternoon, and therefore could do nothing but preside. So Prexy and I walked around the grounds while the procession was forming and I dashed off to line it up or do something and finally got him in the line. Then, I was absolutely frantic, but he had an engagement so he left shortly after lunch and I got back to routine. One snowy day in February I got a telegram…

You mean this was the next year?

The following February—February 1940… “Will you consider the post of substituting for Warden next year? Please come up this week-end.” So I (laughing) thought well, I can’t ignore this! I won’t miss a chance of getting back to college. We just had a six-foot snowstorm, it was Junior Prom week-end when I arrived and had all the usual interviews.

Who would those have been with at that time?

Well, it was with Prexy and I obviously saw Nenny Dodge. Those were the only two formal interviews.

Had you known Nenny Dodge?

Not at all. And it was Junior Prom, and my only time with her was to spend a few minutes chatting in her bedroom because she had the Prom Committee for breakfast that Saturday morning. Then I went back and had lunch with the MacCrackens and then spent Sunday evening with Mildred Thompson… and her advice was “don’t touch it unless you are assured that you can return to Harcum.”

You mean after your one year…

Very shortly thereafter I was offered the job and was assured by Harcum that I could come back so that’s how I came to Vassar—all from running a Commencement…

Well, let’s plunge right in. Can you describe what your life was like in your first year as Warden as well as your year as acting Warden?

Early in the summer, I had to come up to do rooming. Prexy’s family was staying at Yelping Hill. This is the time that I saw the most of Prexy as he was not very busy and had time to chat. There were very few people around—certainly none that I knew.

C. Mildred Thompson wasn’t around?

I think she was away all summer because she had had an operation.

Had Nenny Dodge left you elaborate descriptions of the process that she employed to house people, for example, or did you have to figure it all out for yourself?

Oh, she left good general directions and she had a secretary…

Who was the secretary, do you remember?

No, and it’s just as well I don’t (laughing) because I found the secretary was the best-read secretary at Vassar College (laughing) and none of mine ever earned that distinction. But, we got through, and we got students housed and their room assignments out. And then… oh there were some funny things it was still in ’40, a period of formal calls. I had to have an “At-Home” every Thursday afternoon and…

Pardon me, but did you live in Pratt House?

Oh, yes. I would leave the office promptly at 3:30 p.m. to go home. I guess my first caller was Eloise Ellery. She called with cards, hat and gloves. Quite a few of the senior faculty, some of whom I had known well and some I hadn’t, made calls. Then you had to arrange to return the calls, of course. I also had Student-At-Homes, and those were fun, when I got to know some of the students.

When you returned the calls did people like Eloise Ellery have At-Homes, also? So you had to find out… or did you find a card or something?

Most of it was published in the Directory.

Did all the members… or a lot of the members of the faculty have At-Homes?

A goodly number of senior faculty did. I don’t think junior faculty ever did…

Very pleasant custom, I think.

I began to find my way around thanks to a tremendous lot of help from both Prexy and Mildred Thompson. I always had a weekly meeting with the President, formal appointment and could see him at any time. Mildred I dropped in on very frequently. Then, I gradually began to feel a little more settled and in February Nenny resigned, and to my delight, as I was thoroughly enjoying existence, I was appointed Warden and then felt free to begin to make some changes in procedures and plans.

Can you remember what some of those were and in general what did you think needed changing?

Well, I think I… a little more consistent work in the outer office (laughing. ) I quickly got a superb secretary; the one that Nenny had was going to get married and it worked out very well. Of course the War changed everything. In fact, one of the really difficult problems during the fall of ’40 was the open conflict between Prexy and the Dean. The Dean headed the “All-Out Aid For Britain,” and Prexy headed the “America First.” I had to work with both, but the feeling was so bitter that there was not terribly much communication between either side. And this continued right up until December 7, 1941. One of the really significant moments that I recall was the College Assembly, called the morning of December 8, when Prexy stood up and said that he had opposed the War, had opposed the U.S. involvement in European affairs, as everybody knew, BUT he was above all a Constitutionalist, and the U.S. was now at War and all his energies would be devoted to the War effort. For anybody who had been caught between the two stands, it still was an impressive speech for which I had tremendous admiration for Prexy. I think this was the final straw, though, in wearing him down to almost a feeling of bitterness…

Before we go on to talk about the War period at the College, during the ’40s, I wonder if you could say a word about how the College seemed to have stayed the same or changed between the years when you were a student and when you came back as Warden.

As I said a little earlier, there didn’t seem to me to be any fundamental change in the college that I had left and the college to which I returned ten years later. The composition of the student body was still the same. There were many old traditions still in existence when I was a student; compulsory chapel was held until the fall of 1926 and became voluntary that November. Step-singing [Serenading] still took place, if not quite as regularly, almost as regularly, there were still the soph. and junior parties, there were still the junior and senior proms, Philaletheis still put on three hall plays, the four major organizations were still engaged in active programs…

And would you name those four major organizations?

Philaletheis for dramatics. Athletic Association, Political Association and the religious association that shortly became the Community Church. There were a lot of minor organizations… I should also say the Miscellany News… which, while it didn’t rate as one of the big four, was the equivalent…

Was there the Chronicle also?

No, the Chronicle was a later period. There were more night leaves; in fact seniors had unlimited night leaves which was soon to show its effect on extra-curricular activity but I was not aware of any tremendous difference in the patterns of activity, in the general attitudes, behavior of students, during that first year. The tremendous change came with the impact of the War on the College and the necessity for a more liberal approach to many areas, and then I think the Post-War years represented, in my opinion, the greatest change in the College.

Well, we will go on on our next tape to the War years, thank you very much.

Part II: January 28, 1981

Today is January 28, 1981, and I am continuing my discussions this morning with Elizabeth Moffatt Drouilhet who was Warden of the College for many years. This morning we are going to move on in our discussion to the post-war years. This brings us into a period when there was a changing of the guard, Henry Noble MacCracken left the college, retired in 1946, and Sarah Gibson Blanding came in as President. Do you have any particular memories of this changing of the guard, Betty?

Yes, there was great excitement that Vassar was to have its first woman President. Sarah Blanding came from Cornell. I was particularly interested because before going to Cornell she had been Dean of Women at the University of Kentucky, and I looked forward to working with a President who had more specific notions of what the non-academic administration was involved in.

How did that work out over the years, were there big changes?

Oh, it was fascinating (laughing), the difference between Sarah’s, Prexy’s, and Alan’s years. Sarah had to be in on everything. Most of the disciplinary—serious disciplinary interviews were held with three, the President and me and the culprit. I loved watching her handle an interview, because you could just see the former Dean at work.

But—and this is true—and this is why I was so conscious all those years that Sarah’s initial professional experience was the same as mine. You never reported anything to Sarah. Sarah had to go through it all herself—whereas Prexy and Alan wanted final reports, no going through the process. But, I can go on from here and recall one amusing incident. Two very responsible students came to me during Sarah’s early years and asked if they could discuss a most serious problem, which dealt with the President, and I said yes, I would treat it confidentially and would give them whatever help I could. And they came out and said, “she is absolutely marvelous, but she swears all the time” (laughing) “can’t you stop her using the word ‘Damn’ in every sentence?” I am not sure that they enjoyed my reaction because all I did was laugh and say, “don’t you know Southerners use ‘Damn’ in every sentence they speak?” (laughing)

But, I may also add that those two students have become close friends of Sarah’s.

How was it in general, in those years backing away from the situation a little to make some generalizations. What was the. state of the college in those post-MacCracken years, it was on the heels of the three year/four year struggle – I guess when Sarah Blanding came in there were still repercussions of that struggle, weren’t there?

There were not only repercussions when Sarah came in but there were still repercussions when Alan came in almost 20 years later (laughing).

Which was 1964.

Yes. I think the post-war period was one of the gloomiest, certainly the gloomiest period in the 50 years that I have known Vassar College. The faculty were divided. They still felt the division, one side did not speak to the other side, either—professionally or personally. You would look the other way as you walked across the campus rather than to have to just nod good morning. This was particularly hard in some of the departments because all the departments were not lined up on one side or another. They were also hard years for making ends meet financially.

This was the period—somewhere around here was the Bernard Baruch financial study, maybe… Speaking of studies, all we did was study.

What did you study?

We (laughing) studied ourselves ad nauseum.

Are you referring to the Mellon program now?

I am referring to the Mellon program, but I think a little later I will treat that as a whole.

A generalization which I hate to make, but I am afraid I have to make it, is there was no real leadership. Sarah Blanding was caught between warring factions on the faculty; the faculty-trustee disagreements; and as I look back at the national picture—it is hard to realize that this was the time immediately after the War, when the whole feeling in the country was that A WOMAN’S PLACE WAS IN THE HOME. I can recall vividly sitting in the faculty meetings, debating what should be the aims of the college to be stated in the catalogue and it was proposed by a member of the faculty that one of the aims should be to prepare students for graduate school. The Chairman of the Board of Trustees who was attending that meeting rose and said that can’t be included as one of the college’s aims. This is just an example of the total division that existed.

I have heard that this was a period when the alumnae and the faculty were pretty divided also. Was that so, do you recall that?

Yes, I recall that very definitely. I think the faculty felt that the alumnae were playing too direct a role in the day-by-day administration of the college and certainly in the planning. This was often attributed to the fact that the President’s house wasn’t ready for occupancy when Sarah Blanding arrived. In the first three months of her Presidency, she lived in Alumnae House and this direct line to the President was the thing that was resented very much by faculty who felt that the alumnae, through the association’s Board of Directors and through alumnae trustees, were dictating too many aspects of college policy. This was most important in the realm of admissions and of scholarships.

Oh, yes. Could you speak about that?

I think that the scholarship history of these years is a most interesting one. At that time Vassar had relatively limited funds. There were certain large scholarships, four total scholarships for American students, which had been endowed in the 1870s I think, when total room, board and tuition was $450. The college, out of its limited current funds, had to bring each of these scholarships to full tuition, which by then was $2,000 and getting over. We had some endowed full scholarships at current tuition level for foreign students; but I can remember sitting through scholarship meetings, trying to decide whether our limited funds could best be used to help the medium-income student who needed some assistance to come to Vassar; or whether huge scholarships should be given to students who had no funds whatsoever, thus limiting the number. This went back and forth throughout this whole period and beyond. Occasionally the alumnae would want a special student brought. But the college had less choice in scholarships in this period than one would think because the alumnae clubs were simply marvelous in raising the club funds, but with the exception of a few of the large clubs, such as New York and Boston to mention the two biggest in particular, each alumnae club scholar usually needed supplemental Vassar funds, so there was a very small amount of money available for the scholarship committee to award to non-alumnae scholarship students. I think one of the best examples that I can give of the alumnae control—I guess control is not quite the word, probably a Freudian slip…

It was a period, I think we all know, of national turmoil and upheaval, and maybe we were only a mirror image of what was happening in the world. It was a period that focused on one of Vassar’s greatest handicaps, and that’s its geographic location. Our students felt that they were totally isolated from the opposite sex. There were any number of attempts to try to counteract our geographic location…

What were some of those attempts?

Well, it started off as early as ’47 and ’48 and I went over and talked to the Dean of Freshmen at Yale to see if we could work out some mixers, joint mixers, and at first he was very apprehensive; he felt I wanted social with a capital “S” groups together, and I said no, the ones that are worrying me—primarily are high school students from the mid-west and not from the East who never get a chance to meet anybody—their friends are all at State universities. And he said, if that’s what you are interested in, that’s exactly my biggest problem here at Yale!

Aha ha!

So, we started off the Yale-Vassar mixers and they would alternate. They were held, oh, two or three times a year. Vassar students preferred to go down to Yale, because there was so much more to do there—but we alternated and Yale came over to Vassar. It was also the period of the Yale-Vassar bike race to show what absurdities one could get to.

What was that all about?

One House, Nicholson was its master, and I can’t remember which one it was now, started off what kept up for a few years, that they would organize a race on bicycles from New Haven to Poughkeepsie. Vassar students made elaborate plans—and this became a problem, fortunately it did not last many years. It was a period when young people were restless—we had the panty raids which affected most of the colleges in the country, we only had a few, but in those days to have a group of young men go into a women’s dormitory during the night was something that turned administrative officers white-haired. It was a…

At this point there would still be closing hours in the Vassar dormitories were there not—I mean do you remember what hour was curfew?

I think it was 11:00 p.m. weekdays and 12:00 and then subsequently 1:00 a.m. on week-ends.

So that just coming in and having a panty raid would be a major operation.

Yes, one in particular, when we got word that a Yale house was going to stage a panty raid, Sarah and myself and two others decided that we would not go to bed, we would sit up and be prepared for it. So, we gathered over in the Warden’s House and played bridge and then would listen, play some more bridge, and finally about 3:00 a.m. in the morning we thought we had had a bad steer, and there was not going to be one that night, but they knew we were too prepared for it. But, it was things of this sort that occupied an awful lot of time.

During this period we were all preoccupied with what we could do to help this problem of Vassar’s isolation. One of the things was to organize buses to everywhere. The students had used taxis; a group of five, six, or seven would hire a cab to go to New Haven, to go to all the men’s colleges. It was a period when the interstate commerce regulations were very serious in regarding licensing for taxis carrying passengers over state lines and I spent much time with the I.C.C. officer who warned us that our students were going to be arrested if they continued to drive out of New York State with certain of the taxi companies. I cite this as just an example of the rather stupid problems that one was confronted with in this period.

We had regular buses running to and from New York City. It has always fascinated me that the pressure for student cars came not so much from the students themselves, as from their parents who got tired of having to drive up to Poughkeepsie to take their daughter home and then drive her back again. The parents’ requests, which I must say were supported by the students, resulted in allowing more cars, the parking problem was quite acute. Vassar didn’t have many parking places at that point, not that it has too many right now. To cite another division, the faculty voted against allowing, first all seniors, and then seniors and juniors to have cars and the trustees voted to have them.

Then the trustees prevailed?

The trustees prevailed. The argument that having a car was part of the academic policy of the college did not hold water, and they provided problems, but not much more so than taxis and buses, there was always worry about accidents and students getting stuck in different places.

You had to give campus licenses for the cars?

Yes, we had to have the cars registered and know which students had cars. So far I have commented on the things that were done to try to improve the state of the student mind in getting them away from the college. One thing we started in the late ’40s, to try to make the week-ends on the campus more attractive was to start showing free Saturday night movies. We got the necessary projector equipment and screens and every Saturday night right straight through the year showed various films. At that time we only had a 16 mm. projector, so that the choice of films available was somewhat limited, but that was a thing…

The films were shown in Blodgett?

They were shown in Blodgett and eventually moved to Avery.

I guess the idea of films came up right after I visited my son at Exeter, where they automatically showed a film every Saturday night. I brought it back and everybody seemed to think it was a good idea and we started the next year, and it is one of the few things that hasn’t stopped (laughing), in fact it has grown!

This isolation of Vassar College affected not only the students but it affected the members of the faculty. Single women found Vassar’s geographic location almost as hard to bear as the students. As I think back over this period, it seems to me that from the end of the War, for twelve to fifteen years, it was a period of vaccillation in everything—the size of the college was one thing that jumped up and down by as many as 200 beds from one year to the next, and then back down again. The reports that were written to decide what the size should be would make a complete story in themselves.

Who were these reports written by?

Oh, the administrative officers and faculty committees. The size of classes—it all related to the budget and also it was the period of expansion in most of the colleges and universities in the country. The G.I. Bill® of Rights brought to mens’ colleges numbers of applicants who previously would not have thought of continuing their education. We tried to decide whether the best choice was for Vassar to keep to our traditional number of around 1200 to 1250 students and be very selective; or whether we should increase the number as we had during the War years, overcrowding dormitories. All of it in the final analysis was decided by the budget. To try to continue as wide a curriculum choice as we offered, with very small classes, and to increase the salaries of faculty members to meet the rising costs of post-war inflation, were in total conflict. We had to increase the number of students, with very slight increases in the other areas, to survive. Keeping a small, selective college was wishful thinking. Our applicant pool was neither large enough nor select enough to make this possible. At this period many colleges went into elaborate building programs. We had space in our dormitories, primarily the three room suites for two, as well as a few luxuriously large single rooms which made it possible to bring our resident population up to around 1500–1550, and so the decision to go to a larger college after all these annual changes was finally agreed upon. It created one major problem; whether the times and the other factors would have produced the same result, it is hard to say, but when we got above 1400 students we no longer could meet together as a college because that was the size, the absolute maximum that could be crowded into the Chapel. We discussed at length what we could do, whether we could increase the Chapel by putting in a larger balcony as Mount Holyoke had done. Smith was always blessed because their main assembly hall was larger than Smith could ever get to (laughing). But it is things like this; when a college can no longer meet together it ceases to really be a completely unified unit. And I mentioned earlier the breakdown caused by the three year plan, and tight class associations and equally strong dormitory associations. There was less sense of belonging than in the pre-war period. I think I said earlier when I came back in 1940 it was the same college I had left. By 1950, and certainly by the mid 1950s (laughing) it had changed completely; it was unrecognizable in some ways more than other places.

One other difference at Vassar, in comparison to some of the other colleges during this period, we did relatively little building. We devoted our small amount of funds to alterations in existing dormitories to accommodate more students instead of building new. In fact I think at a period when many colleges and universities were having a tremendous building program, ours was devoted primarily to small, special units. I think in terms of Ferry Co-operative House and to Chicago Hall. I don’t think it is quite fair to call these luxury buildings, but in comparison to dormitories or major academic additions, they are not quite as essential to the main purpose of the college. The first dormitory we built was Noyes and it is interesting to note that the best we could get at that point was one-third of the students would live in single rooms. The fifties showed some pressure from students for single rooms. In the sixties and early seventies, there was an absolute insistence on single rooms, which we subsequently tried to comply with in the existing dormitories; some by structural subdivisions, into making it possible for (I think it is) sixty-three percent of the students to live in single rooms, as opposed to a very small percentage in the original design.

Maybe this is the point to comment on the problems that Vassar has always had with running an effective co-operative house. I was never able to really figure out why. Most other colleges had been able to run them with the greatest ease; great student interest; long waiting lists. In the year when Ferry was a brand new house, we had more selection than in any other period in the 36 years when I was responsible for housing students, including co-operative houses. But by the second year of Ferry we were back, with really no choice. We tried never to let on, I think in most cases students didn’t realize that an application for a co-operative house, unless they were on academic probation, was almost a certainty of getting in. We couldn’t always apply the test that only those with financial need were eligible. First we thought it was the original co-operative, Palmer, that its location and its age, (100 year old house that had been converted), was one of the deterrents but Ferry for which money was given had the most central location of anything on the campus except Main Building. It was brand new and except for the first year, it has been a problem to keep filled.

By the way, you just said Palmer, which I had lived in as a student, was the first co-operative house; but before that wasn’t there co-operative living in Blodgett?

Yes, that was right in the early part of the Depression when they tried to find every possible way of giving financial aid to students to continue their education and they converted some of the rooms in Blodgett Hall to a co-operative for students and then subsequently took over Palmer House. At that same time a different form of co-operative was that in Raymond House, which was a standard dormitory where students did message desk work and table waiting…

And scrape [dishes]?

No, (laughing) that was subsequently. I think they did prepare salads and received a $100 reduction. That had worked very well and had been a popular means of earning money. But when the co-operative system went in on-campus, then there was no difference.

Perhaps the dominant influence on Vassar College in the post-War period we are discussing was the Mellon Fund and the Mellon program. In 1949, I think, it may have been 1948, Paul Mellon gave two million dollars to Vassar and two million dollars to Yale to develop programs that would assist the group of students who needed guidance and help in making adequate adjustment. This certainly occupied a tremendous amount of time of everyone at the college. There was a faculty committee, there was a student committee. I think it is interesting at the start, to compare Vassar’s use of the funds and Yale’s. Yale went into a psychiatric research center and Vassar developed a whole series of studies and programs to bring assistance to students who needed specialized help and counseling. The first advent of the program was the arrival on campus of the noted psychiatrist Dr. Carl Binger, who brought with him a social scientist, Maria Yahoda, who did an exhaustive study of the student body and the climate of Vassar thought. I can’t remember whether it was a fifty page or a hundred and fifty page questionnaire administered to (laughing) every student. The very mechanics of this is staggering…

The students were required to take this?

Absolute requirement! And take it simultaneously. A special provision was made for students who were too ill to take it in the infirmary or for family emergency.

Were there any rebels who said they wouldn’t take it?

Ah, yes, but they sat down—and there were some questionnaires that had almost nothing marked on them except the name to show they attended. During the period while Miss Yahoda was collating and trying to find out what she had gotten in these questionnaires, the faculty were debating other aspects of the program and there were two very funny… What year did you come?

I came in ’47-’48, so I was here!

Oh, you attended Binger 105 and Binger 210 then, did you? (laughing)

Yes, (laughing) I want to hear what you have to say about it (continued laughing)!

The Mellon program was not the first acknowledgment of the field of psychiatry with Vassar because as early as the mid-twenties C. Mildred Thompson had gotten psychiatric help from Austin Riggs, and as needed, a consulting psychiatrist came from his clinic. But, seldom I believe, had the whole academic community been subjected to a saturation of psychiatric approaches, psychiatric jargon, committees meetings around the clock, the faculty committee met once a week for at least a year. As I referred to at the beginning there were the courses taught, (courses in quotes) to the faculty by Carl Binger to properly present to them the importance of the psychiatric understanding of student’s needs and reactions so that their teaching could become more effective and they could be more useful to the students…

(Both laughing)

My recollections of the Binger period are that it increased the divisions among the faculty; that he violated confidentiality in his interviews with many faculty, many administrators and many students, and that he entertained the world with his four inch headlines in the New York Times on the Vassar matriarchy. In other words, I do not look back on the Binger period as making any contribution to Vassar College. He was followed by Nevitt Sanford, with an entirely different approach. This was a statistical study of the college. Without going into all the details, I think this program was extremely wasteful. It involved more testing of selective groups; primarily the students. Nevitt Sanford and his associates met regularly with the faculty committee and made frequent reports to the faculty to keep them informed on what was going on. But as I look back on it, I cannot think of any real contribution that I think this three, four, five years, whatever the period was, made to Vassar College as a college. We did get a lot of excellent office furniture and brand new machines, which we never would have had otherwise.

To summarize this initial period of the Mellon Fund activity, I think there were two good outcomes for the college. One, was the financing of the House Fellows Program; in the early stages this program had a very positive effect on student life in the house and did in a most direct way bring the classroom and the dormitory together. The second positive result was the financial provision for a resident psychiatrist and counseling services. On the other side I think the first years of the Mellon program had some very bad effects. I think there was too much self-study. A preoccupation with introspection, with self-images. One of the results I fear was that schools had a tendency to encourage their misfits to come to Vassar and to discourage their more able students. I think that as all of us collectively or individually, have only so much time to use, if it is spent on introspective studies, it is not available for the true purposes for which a college exists. And I think the time devoted to these studies during this period had a very, very bad effect. One tangible evidence of this can be found in the confidential report of the Middle States evaluation which took place in the early fifties and gave or rather made some pretty critical statements about Vassar. All reports weren’t psychiatric. During the same period we had the so-called CMP report: Cresap, McCormick and Paget and taken together with the Middle States, because they did investigate college admission, the picture was pretty bleak.

In other words I look back on this first post-war period as a time when the college wasn’t even marking time, I think it was shifting its energies and giving much too much attention to irrelevant areas and I think this, to a large extent, contributed to some of our subsequent difficulties.

Betty, you were saying that the schools began to send us their weaker and more problematic students. That suggests that there were changes in the student body. Do you have anything to say about that?

Yes, I think this was one of the most difficult problems the college had to face. We ceased to get a fair percentage of the most able students from our traditional feeder schools. Instead of getting students in the top ten or even twenty percent, we were getting them from close to the middle of their class standing, (laughing) if not even below that; of those who were offered places and accepted places at Vassar, the percentage of good students was even smaller. At this time there was the beginning of a very real change in the composition of our student body. Up until this period it had come from the upper middle class, through the upper reaches of economic levels, as financial aid was so limited, as we mentioned earlier. We began to get much more money available for student help through expansion of state funds, both in direct grants and in loans, and an influx of federal grants, primarily in loans. This meant that students who had previously never been able, financially, to consider Vassar, were now in the position where they could apply; the college could grant them admission, and they were able to accept their places. And this has steadily increased to the present. I found it interesting that the headlines in this morning’s New York Times say that the Reagan administration is going to curtail much of the federal money for education; so there may be some lowering and lessening of federal funds available. But up to the present, from the past twenty-five years, no student has been unable to attend the college of choice for financial reasons.

Thinking about the sixties, Betty, what comes to mind?

Instantly, relief that the fifties were over and done with, and that the sixties would, as they turned out to be, provide a much more interesting time on the campus with all the hardship and headaches. I think my first recollection of the sixties was the most dazzling experience I think’ I had in my time in office. I was sitting at my desk working one morning when a group of five or six students came in and I asked them what I could do. They said we want to request permission to picket Woolworths. Well, I tried to keep a straight face and swallowed, having been at college during the days (laughing) when students acting on national problems didn’t go and ask permission, I was a little startled and I thought that the first thing I had to do was to stall for time; and I said I really want to go into this more thoroughly with you than I can now, for I have an appointment waiting and I said come back at 2 o’clock this afternoon. Well, it took me thirty seconds with my next appointment and I tore out to Sarah Blanding, who in her day was also a radical, (laughing) and I said “Sarah, it is the surprise of all time. Our students are still so much in that lethargic, formal, placid state that I just had a group request permission to picket Woolworths!” Well, (laughing) we both sat and laughed. Neither of us in our younger days had asked permission to picket. So…

By the way, did you picket something?

Yes! (laughing) I marched… well, picketing in those days was primarily marching. I did not go into any of the great labor things, but many of us marched for causes. Well, I decided that what I had to do was give them a course in picketing. I suddenly realized how the college had changed. That there were no older students with any experience in registering protests.

Isn’t that astonishing!

… to hand down to the present generation what you did. And, (laughing) last of all you didn’t ask permission to protest laws.

We had Drouilhet 105 in picketing!

We had Drouilhet’s 105 in picketing, and the one thing I pointed out to them was if you get in trouble with the law, you’ll be in trouble with the college. You keep the law to the letter, and if you don’t know it, it is that you keep walking the whole time, you cannot stand, because then the law will get you for loitering. You just keep in a march, don’t get into any fights, verbal or otherwise. You can wear the placards you want, if you want to be impressive, don’t dress outlandishly, and good luck to you. It is perfectly possible the next moment I see you may be in a disciplinary situation, but at least… take care and do it! So, this was to happen either that or the next afternoon, I don’t remember which, and it turned out to be a rainy day. But Sarah and I borrowed somebody else’s car and drove down Main street to watch them, and it was a very impressive sight. And, it was a great, great relief to me for I thought maybe the students can take some interest in something except their own mental health (laughing).

As the sixties progressed, this picketing was certainly the tiny iceberg showing on the surface because the new generation of young people, the activist generation, was apparent on the Vassar campus as well as in the country as a whole, and we certainly had our share of the problems that were facing the country.

Part III: June 16, 1982

Today is June 16, 1982, this is Elizabeth Daniels and I am continuing my interview with Elizabeth Drouilhet. Betty, this morning we are going to discuss the building that took place during your administration.

Well, from the time I first got here I was a member of the various campus “Planning” building committees and on many occasions sat with the Trustee Committee on building and grounds. Vassar had done a great deal of building under Dr. MacCracken, but obviously during the war years there was no building of any sort. We did not start right off in the post-war period, but soon began to realize as the study body had increased and the old academic buildings were feeling the additional numbers, that we should do something. I am grouping these just under their three main heads starting off with the academic. The first of the academic buildings that I had anything to do with was Chicago Hall. We had an amusing committee which I chaired called the Committee on Academic Space which met with all departments separately trying to decide who needed what the most. You undoubtedly recall that the country went mad on language laboratories. The war had developed the techniques for rapid-teaching a language through tapes and our language departments felt that this was absolutely essential, particularly for some of the unusual languages such as Chinese and others, but also to supplement their work in the traditional ones. Well, we heard everybody, every department’s needs for additional space, and what, where and how. One of Sarah’s [President Blanding] first promises was that there would be a new science building as the space available for science in Blodgett was inefficient and cramped and the old science building simply did not meet the needs. Well, this was never done in her administration, but with the help of the Chicago alumnae we started in on Chicago Hall. The first architect presented a plan that had about six inch vents at the ceiling, of the wall ceiling, that gave a little bit of light. Well, our departments would have none of it. They flatly said we have not come to teach in a country college to have to use artificial light in all our classrooms and all our offices. So, that architect was thanked and dismissed, and another one took over who was the one that produced the building that we currently have. There was as much discussion if not more on that building than anything that I ever had anything to do with. Each department knew what it wanted, and quite obviously wanted more than there was any possibility of paying for; but they did come out with a language center for each of the main languages�classrooms, too few offices and the basement for the language laboratory, which at that time, had some of the most modern equipment available. So, that was my first experience of anything to do with academic building.

Then continuing the academic line, I guess, in chronological order, the next thing was the remodeling of the old laundry for the computer center. At the time that it became obvious Vassar had to have a computer not only for the working of the college, but for the teaching of computer science which quickly became one of the major branches of math. The college after the war was not able to continue its own laundry. It seemed possible, if not suitable or adequate space, and the computer was put in there and it is still there today, taking over a little more each year.

Then, finally, under Alan Simpson the new Biological Science building was built. I personally think it is one of the most beautiful science buildings I have seen and everybody seemed quite pleased with it, and as far as I know to the present, it is adequately meeting their needs and it does give the protection and availability for use to the electronic microscope which is one of the major pieces of equipment the biology department owns.

I left chronological order because the Lockwood Library was built and finished before the science building which created fascinating problems. The “Class Tree” of one of the Trustees on the Building and grounds committee was located just in the spot in which the architects wanted to put the building. It would be hard for me to describe the hours we spent and the number of trips to New York on the committee’s part or the architects coming up here to see how you could put an addition to the library or the new Lockwood wing without harming that famous maple tree. Well, I remember sitting one afternoon in Bob Hutchins’ office; we had been going for about four hours, just beating about the bush and getting absolutely nowhere and suddenly I said “well, I think there is a way one can do it; I don’t know whether it is architectually feasible or not, but why not build around the tree and if you aren’t going to build the east-west wing at this point, leave space to put it there and form the additions needed in the future.” There was sudden silence, everybody got thinking and Bob Hutchins finally (he was the college’s consulting architect for all the time I was here) said “I think you’ve got it.” He said we’ll make all the necessary checks with the architects, and we’ll let the committee know what it worked out. Heaven only knows, it is a very old maple tree, how long it is going to survive, and in the future people may say why was it ever put here, but at least it got (laughing) the library started.

During this period there was, before the Lockwood Library, there was a major renovation of the main Library with a gift from Elizabeth Stillman Williams, which provided many needed improvements which is not always easy in one of these old, strong buildings. Also, during this period there was some work done in Rockefeller to make more offices for faculty and more convenient space.

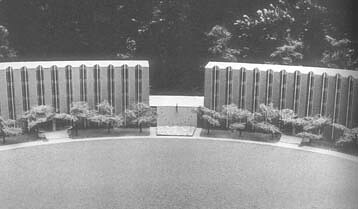

Moving from the academic buildings to the general buildings, the biggest thing done there was the reconstruction of Students’ Building to serve as an “All-College Dining Center.” After our last old chef reached retirement age and it was not possible, and had not been possible to replace enough chefs to keep open the college dining-rooms and to operate them, which everybody said well, why did the college ever do it? Well, this is the frank reason that it was done, we simply could not staff with chefs the separate kitchens. There were many plans for this, I think it’s interesting to remember that I.M. Pei produced one for putting the college center on the grass plot between Strong and the Aula. Many ramps and a multi-storied building. Well, (laughing) this, frankly, was discarded, nobody quite liked it. Then there was a plan, and I can’t remember which architect worked on that [Harmon Goldstone], who was putting a dining center in the middle of the quadrangle which would have links with four quad houses; the other houses would have to walk outside to get to the dining center. Well, that did not solve all the problems and really did not become a feasible solution to it, and finally an architect we agreed upon, who designed the present alterations to Students’ Building. I think he did a magnificent job-I think that it looks better from the outside than it did before. To those of us that knew it, it is amusing to think that the perfectly stunning Adam-type ceiling is now over the dishwashing room.

There was much opposition and there was some loss to dormitory life because it is no longer as definitely centered in the houses as it was when you ate in your own house. But it was practically used for years; we spent money and a great deal of time trying to think what to do with Students’ Building itself. When I was here it was used all the time—all extracurricular groups met there, the Phil plays were put on there, it was used as the main lecture hall, it adequately seated the college, you could put 1000 in there, and the college was near enough 1000 that we rarely had an event where it was overcrowded. But when I came back in 1940, after the ten year period, almost nothing happened in Students’ Building. In the intervening years, it somehow… groups just didn’t use it. If one was told they had to have a lecture in Students’, they almost cancelled the lecture, rather than put it there. This continued and we thought of one thing after another; there were various remodelings and refurbishings of the building, but it always looked like a run-down, abandoned spot and up until the time that the proposal came to use it as the dining center, it was sad, because it was a lovely building that had just gone down, and we sank money in it, redecorated it, did this that and the other thing and still nobody wanted to use it.

Well, as far as I know, and have been able to observe, it has worked very well. With all cooking and food preparation done in one spot the college has been able to staff it, particularly since the Culinary Institute came up to Hyde Park as our near neighbor, and it is a wonderful practical experience for many of their students which has certainly helped our food preparations. You get about as many gripes as you get from students from any college dining, but on the whole I think that they really do a very good job and there is any number of choices, as those who have been in the building know, and there is one large west dining room, and then there are small dining rooms, some of which can be used for private meetings.

Then, in general, I think the next main alteration that happened was the building of the College Center. It became very obvious as the—I started to say years, I guess I had better say decades—moved on that we had no real focal point for student life if one must so put it. The dormitories functioned; Main less satisfactorily than others because it was so large and so dispersed, but at least we kept Main as a dormitory, encroaching frequently on its space for additional office facilities. But, we had talked and we talked to various places, where a college center could be located. We had long out-grown the facilities of our post office, and it was a safety trap, with high boxes and inadequate corridors with the mail rush, so we spent a year to a year-and-a-half going over various possibilities. And I for one think Carlhian did a magnificent job in preserving as much of the original Main building: the parts that were torn down were only the additions put on much later on. While you can’t see them, he did open up the old chapel windows from when the chapel was above the dining room, and had the stained glass windows. His using the atriums to preserve the original brick walls, in fact even after this many years, I can find very little fault with anything he did there. I am happy to say he won many awards for this addition to an original building. I think it is one of the most distinguished we have.

I think that pretty well covers everything but what we did in the dormitories, which was of course, of all things, what I was most directly involved in. We talked some time, after the war when first our numbers see-sawed up and down, then down and up, and up and down, so nobody ever knew what the size of the next year’s college, let alone the year after that, would be. As I think I said earlier, we varied as much as 100 to 150 students in successive years, either up or down… usually depending on I must say, the state of the budget. If the faculty needed a salary increase, I was told I had to have an extra 100 students (laughing)! At this time many of the, most of the colleges, and certainly along with it most womens colleges, were engaged in extensive building programs. Finally, we decided that we were just too crowded and if we were going to maintain the college at that level, we would have to have a new dormitory.

The college hired Eero Saarinen to design the dormitory. One of our specifications was that we needed just as many singles as possible — in fact I would have been delighted if we would have built a building with nothing but singles. Well, we came out with a third of the space as singles, with half doubles and half singles. It was built to have a link and an identical second half. The second half has never been built and I doubt very much if it ever will be built. It certainly is the most modern building in all senses of that word, that we have on campus. The living room has a sunken pit, but on the whole people have adjusted to it. One thing that the architect certainly made no mention of and the rest of us didn’t think of at the time, was the curved corridors used to act as sound amplifiers. The bay windows in the front of the building transmit whispers from the first floor to the third and fourth. Nevertheless, it is attractive as modern buildings go, and it certainly has been useful. We finally, a few years back, changed its dining room at the time we changed all of the dining rooms and converted them into single rooms. Noyes had adequate extra space, small social rooms, so all of the Noyes dining rooms converted. The kitchen wing was converted to an all purpose meeting room for the college

as a whole, so it had a separate entrance.

Then, sort of following in order, we did minor alterations to the dormitories, the major ones happened in the early ’70s. Of the new housing, there was a time there when the fad across the country was for students to live off-campus, and we had to get more space because we were continuously increasing our numbers. I met with a student committee and they said “Well, if you would only build apartment types we would much rather live on campus, we don’t want to go off and rent Poughkeepsie houses: it is just that we want apartment-type living”. So Bob Hutchins, who for years had been the college’s consulting architect, came up with a system of town houses to be built over on the farm. They have worked out quite, although most people said they wouldn’t survive, they would fall down in ten years. They have drawbacks, but as the trees have grown up, and the wood has weathered a bit, I personally don’t find them objectionable at all, I find them a rather attractive group of housing.

Going on to other housing, a year after we put up the Town Houses, which was a period when the college was increasing its numbers almost yearly, we still needed more housing. The Terrace Apartments were built up on the edge of the golf course. Each of these units has four students, whereas the town houses have five; they too have worked out pretty satisfactorily. It has amused us, we thought of it as junior-senior housing, but the seniors find the housekeeping responsibilities a conflict with their thesis, and has become more sophomore and junior with a few seniors.

The other new housing that was built shortly after the war was the Watson houses for members of the faculty. If we were desperate for student housing, we were more than desperate for faculty housing and certainly at a price the faculty could afford to pay. The whole housing situation in the college area changed after the war when IBM set up its big plant here and its salaries were far (laughing) beyond anything that the college could meet, and it was a very large influx of non-local people, and they took all the apartments and all the houses in the whole area that had formerly been available. Their standard rent, standard housing allowance for their employees, was double what anybody could expect a Vassar faculty member to pay, so more and more of the faculty either had to go out of this area and commute quite a distance, or find college housing. So, thanks to a starting gift from the Watsons, the college had built the Watson houses, one of the first modern type constructions on the campus, and again built in the old asparagus field so that until the planting grew up, they were thought of as an eyesore. But they are very convenient and very efficient units. There were six, three bedroom units, and the others were four bedrooms; two bedrooms up and two bedrooms down. The cost of maintaining them has increased year by year, as it has with everything else, but originally they were limited to the younger and newer members of the faculty.

Finally, there was a general reconsideration of all the faculty housing policies in the early ’60s. A certain number of the Watsons are held for each year, for incoming or new faculty, but otherwise they are open to applicants according to priorities established by the faculty housing managements.

Well, I think the only other thing that I want to comment on is the remodeling of the dormitories which happened in the early ’70s. Our dormitories from Matthew Vassar’s original Main building, right through the last one built, Noyes, had comparatively few singles. The one demand of students was “I don’t care where I live. I must have a single room,” and I think this was a universal trend after the ’30s. I think up to that time a high percentage of the students not only preferred doubles but were perfectly happy to live in doubles. But from the ’40s on it was just the continuous cry, we never could meet it. Well, we thought long and hard as to what was the best thing to do. Our dormitories were soundly built, they were very old, they had old heating systems, they had old “this,” “that” and the other, but one couldn’t really think of tearing down and putting up nothing but modern housing, nor could you afford to heat them and not make them useable. So, we went through building by building over a period of quite a few years, and converted the majority of the space in every one of the old houses into single rooms. In many cases it called for pulling down walls, and you’d get quite a difference in the size of rooms, but since you had three and sometimes four classes living there, the little singles were cut out, which were the old bedrooms for the three room suite, were those that were old. We did this right straight around. The one that really defied us was Josselyn; which had either much too large singles or disproportionately small bedrooms in their three room suites. Joss still has a great many one-room doubles and we converted the suites into a large single and a small one. Well, I can’t remember the actual figures, but we not only provided additional singles but also were able to have a larger number— and my final work in remodeling was after we went to central dining. We had the old kitchen to work with and the old dining rooms and we converted in all the quads, I guess in all the houses except Jewett, where the kitchen needs replacement; the kitchens into bedrooms and the dining rooms into much needed lounge space because with the number of students housed, our activity rooms were too small. We have ping-pong rooms set up in the basement, with a good student kitchenette in connection with the lounges. I think it made our old dormitories much more pleasant places to live.

I don’t think you have mentioned any place the conversion of faculty accommodations in connection with the faculty fellow program. Could you say a word about that?

Oh, yes. In the late forties, either ’49 or ’50, I don’t remember which year, the college was recipient of an enormous endowment from Paul Mellon.

We have talked about that, and we have mentioned the faculty fellow program came in, but we didn’t specifically talk about the dormitory apartments.

Well, up until that time there had been single women living in the dormitories as residents, and they had a living room, bedroom and bath. Period. When we decided on the house fellows program we wanted it to be available to families and each apartment must have two bedrooms, a study, a living room and a kitchenette. So, the ends of the quadrangles, in fact the ends of all the old dormitories, were taken over for house fellow apartments, for the large apartments, and the old head resident rooms were added to to make a small house fellow apartment because there were to be two in each dormitory. In the only new building, Noyes, it was built in, and this has worked out very well. Somehow or other, we had to absorb the loss of space because the house fellows, while they physically displaced in most houses about 10 students, I was directed that we could not decrease the number of students housed in any one of the buildings. So for a period there, until we were able to make other alterations, or as our numbers fluctuated year by year, we were using mostly singles as one room doubles. At the present I think that as we increase the number of resident students, at any point, we are going to have to build new housing, I just do not believe that…