William Smith: Steward to Vassar College

The Great Experiment: a familiar epithet for Matthew Vassar’s ever-growing enterprise. Less familiar to most are the hardships and difficulties borne by a select few at the founding of the college. While the trials of presidents, trustees, and faculty have all been well documented, several others have been seemingly lost in the shuffle. Enter William Smith, the first Steward to Vassar College. Though his tenure may have been short, the scandals and crises he oversaw cement his place in the annals of Vassar history.

The Steward position was created by the Executive Committee of Vassar College before the school opened in 1865. Under the supervision of the Superintendent, the Steward was delegated several duties. As stated in his contract, the Steward tended to “matters of every kind connected with or related to the domestic department.” This “lower department,” as it was described by one applicant, concerned itself with the minutia of the college – enforcing dining schedules; providing meat and produce for the kitchen; carpentry and gardening; linens and laundry; regulating the employees; and generally claiming responsibility when blame was dealt. Thankless as the work was, three men applied for the position.

Dinner at half past four – no after meal –

Oyster Soup

A Turkey (roast) at each table

Mashed Potatoes – celery – squash – fried parsnips – cranberries – picked beets

Poor Man’s Plum Pudding for each table (ask Miss Lyman how to make it)

Coffee

Apples

If this pudding can’t be made ask Mrs. Campbell about a Bedott Pudding

Mr Smith – the above bill of fare is desired on Thanksgiving DayC. Swan

A letter to the Steward, November 1865

In 1863 a man by the name of James Taylor forwarded his references to the Executive Board along with a list of qualifications. Taylor emphasized his strong family commitment as well as his past experience in a factory. His only request was that his wife be given a position in serving any “indoor calling” the committee may have for her. Another applicant, referred to only as “Mr. Gibbs,” seemed content in merely attaching his name to Matthew Vassar’s vision. He wrote to the founder, “I have an increasing desire to come into your college somehow although a stranger to you. I feel I could be a great service to your seminary, just give me an opportunity to make your acquaintance.” His letter of application was even more direct, reading in its entirety: “I should like to make an application as Steward of the Institution. An answer as soon as would be convenient is desired.”

The final applicant, William Wallace Smith, approached the Executive Board with a slightly different attitude. “I bring you now no written recommendation” he announced in his application, “because you either know me personally or are in a situation without troubling yourselves to get information.” The son of James Smith, a Scotch Canadian who migrated to Poughkeepsie in 1847 to start a restaurant, Smith was well acquainted with food services at an early age. Banking on his local reputation, Smith’s application was very matter-of-fact: “I have made the purchases and personally superintended the cooking department of our house for some years. I am a practical man in every branch of this department.” Smith’s confidence obviously influenced the board because in 1864, the Executive Board mailed him his official contract of employment.

Inventory of Knives and Forks in the Steward’s Dept. of Vassar Female College March 3rd, 1866

396 Table Spoons

From the Steward’s notes

54 Butter Knives

54 Sugar spoons

55 Salt Spoons

56 Mustard Spoons

610 forks

365 Dinner knives

331 Tea Knives

541 Tea Spoons

The contract outlined Smith’s imminent employment for 1865. He was to be paid a yearly salary of $600 at a quarterly rate; furthermore, he was required to move his wife and two children onto campus after August 1865, where he would serve the college full-time. The school provided “the usual college supplies and also heat and light” to Smith, as well as a “plainly furnished” room “with carpets and all necessary wood furniture.” For his troubles, Smith was compensated with a one-time payment of $1,200, also paid quarterly. In comparison, most professors were paid approximately $2,500 per year. Though he was well compensated by the college, the work proved more arduous than Smith expected.

In his year-end report to the Executive Committee, Smith was clearly agitated. This report, he claimed, was “for the purpose of showing [the committee] the difficulties and embarrassments and counteracting influences” with which he had to contend as Steward. In the report, Smith admitted he knew very little about what was expected of him. “Although I often made enquiries on that point,” he lamented “no one of course knew how to adopt plans or rules.” Evoking the power of pioneers before him, he wrote “it was in most part an experiment, all being strangers to each other and everything being different from anything of the kind seen before…” Before citing the numerous disasters which occurred that first year, Smith framed his testimony with this foregone conclusion: “Experience must be our teacher.”

The workers, he continued, “some from New York, some from Poughkeepsie, and others as they came along,” were a ragtag group with little in common. Smith claimed the workers “never related to each other.” Adding further tension to the group’s dynamic was the issue of inadequate bedding. With an insufficient amount of bedding and mattresses, several workers slept on the floors, some without blankets for months; others opted to sleep three in a bed. It was months before the college could even accommodate two in a bed. Coupled with extreme summer heat, the persistent overcrowding created a potentially dangerous situation. It seemed “for months that the very elements conspired… to keep my whole department in a perfect boil,” he recounted to the board. Forced to house six to twelve people per room under these conditions, Smith was constantly on the verge of disaster.

The rocky relationship between Smith and Cyrus Swan, the Superintendent and Secretary of the Executive Committee, quickly became apparent in the Steward’s writing. Superintendent Swan acted as a liaison between the Steward and Executive Committee. When things went wrong, as they often did, the Superintendent was supposed to accommodate the Steward’s requests for aid. “Many things were left undone until long after the opening of the college” Smith complained. To make matters worse, he “appealed to Mr. Swan to have [these things] accomplished in season, but he continually objected and questioned the necessity of such and such kinds of work.” With a tinge of bitterness, Smith recounted: “As a matter of course, I received the credit for all the confusion and mishaps that followed the want of these conveniences.”

Smith went on to remind the board of the refrigeration fiasco he was forced to address. Swan ordered the contractors to place the school’s refrigeration unit (i.e.: icebox) beneath the kitchen in the basement. The Steward was vehemently against this decision, as it was not only inconvenient for staff, but also strenuous for the equipment. Swan ignored these warnings. As Smith had feared, the icebox broke down, leaving the school with $300 worth of tainted meat. Worse yet, the discovery came too late for recall, putting the health of several students at risk. “You may imagine how embarrassing for me at times when I depended upon my dinner or breakfast as the case may be, [to] find it spoiled…this has really happened a number of times,” the Steward confessed. Smith may well have jeopardized his employment with this ominous assessment: “Were I to make an exposé of all the deficiencies arising from the want of [a new] cooler it would not only surprise but cause many unpleasant feelings.”

Another issue that arose between the men involved a Mrs. Campbell and her daughter, whom the Steward was asked to cater to by Swan. Being a man of systems and organization, Smith was appalled by the special treatment Mrs. Campbell requested: “This morning Mrs. Campbell ordered cake for herself and then furnished the whole table with them. And just that little variation from my established rule brought every waitress to me with complaints because I did not allow them the same privilege… you will very readily see the necessity of observing rules and regulations.” Smith once again verged on a veiled threat in his Executive Committee report of the incident: “Mrs. Campbell and daughter have caused me more trouble in every way than the whole school put together, particulars I withhold at the present.”

By December of 1865, the illusion of courtesy between the men had all but vanished. On December 5th, Swan wrote:

The waiting in some parts of the dining room is very defective…I have heard for weeks of persons waiting from twenty to thirty minutes at table before being waited on. There can be no good reason for it. The dinner today was poor — besides numbers had no taste of meat because there was not enough. This course of things continued will ruin the college…

Yours etc. C. Swan

The next day, Smith replied tersely:

…the dinner yesterday that was served up to the school was a good one although I was not home to see it… the beef and pork and lamb stew all could not be nicer…The fact is complaints come from persons who never had enough at home, and what they did have was of such a poor cheap quality and so little of that even that they don’t know what good living is….

I have no favorites in the house and all are alike to me. I know no difference in individuals, this of course is against my popularity. I am sensible [that] I am not a favorite among many. This I cannot help. It may be unfortunate for me; I do not know, and more, I do not care. I only know my duty, this I will do to the best of my judgment and ability. When there are real mistakes and errors I will be most happy to be informed of it and always try to do better.

Swan forwarded the letter to the Executive Committee soon after. Upon its presentation to the board, Smith was chastised for being “disrespectful and improper.” The committee members responded with this warning to the Steward – “such conduct deserves our notice and condemnation.”

Whether Smith’s troubles were the result of constantly claiming responsibility for his co-workers’ lapses or the product of his own forceful personality is unclear. Letters from Smith’s notebook provide a sense of his rigid temperament. On November 30th, 1865, Smith wrote: “I am so annoyed with the present mode of timekeeping in the Dining Room it will become a necessity either to furnish me with the correct time or I will be obliged to serve my meals according to the true time of day…I must be governed entirely by the true time.” Are these the words of a tetchy malcontent, or a meticulous worker? In either case, Smith would have us believe that Superintendent Swan was responsible for his moodiness.

After summarizing the hardships he had to endure throughout his first year, Smith included a section in his Executive report that dealt exclusively with Swan. Though he presented his case tactfully – “I do not speak of these unpleasant things for the purpose of creating any trouble with any person” – his allegations were nonetheless serious. “He has never been in my office to consult with me since I came to this college,” Smith wrote of Superintendent Swan, “this I think is a mistake.” Smith added: “Mr. Swan’s manner towards me and mine have at times been very abusing and insulting, indulging in the most violent and abusive language.” While these claims remain speculative without written proof, ample evidence of Mr. Swan’s insensitivity exists. In a memo to the Steward, Swan wrote: “I observe a small child about the dining room. It must be removed as we have no places for such small people, at any price.”

At the close of his exhaustive report, Steward Smith included this final sentiment: “Very few can fully appreciate the difficulties and perplexities with which I have had to contend.” Shortly after receiving Steward’s annual report, the Executive Board was sent to deliberate on Smith’s future at Vassar. On June 16th, 1866, Smith received word that his contract would not be extended to the next year – the news came just two days after Smith submitted his tell-all report. After a solid year of frustrations and calamities, William Smith was sent home.

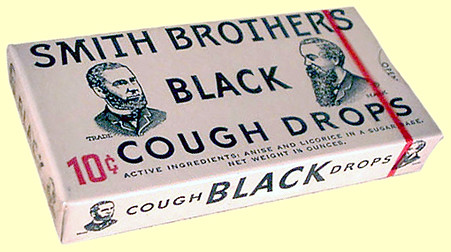

Although Smith’s term at Vassar did not prove very fruitful, he went on to find greater notoriety without the college. After briefly selling tobacco and cigarettes, Smith bought his way into his father’s catering business. With his business partner and brother Andrew, the duo brought their father’s business to new heights under the name “Smith Brothers.” Their greatest claim to fame was their renowned cough drops, famous nationwide not only for their sweet taste but also for their memorable box art. On the cover of each package, the company’s trademark, the Smith Brothers’ bearded faces are displayed with the words “trade” and “mark” adjacent to each image, making it appear that the brothers’ names might be Trade and Mark Smith. The former Steward, William Smith, was immortalized as his fictional counterpart Trade, while his brother Andrew became Mark.

In 1895 The Search Light, a Poughkeepsie publication, featured William Smith as a local celebrity, in support of his candidacy on the Prohibition ticket for New York Secretary of State. It seems ironic that Matthew Vassar, a well-known brewer, would have hired a future prohibitionist. Among the brothers’ achievements – the uncanny success of their cough drops, their famous restaurant, and their careers as caterers, with a loyal following all across New York State– the article never mentions Vassar College.

SOURCES

“Smith, William Wallace (Steward, V.C., 1865) Biographical File

“Steward’s Office Applications for Position of Steward,” Subject Folder 5.70

“Steward’s Office Contract for Employment,” Subject Folder 5.71

“Steward’s Office Correspondence w/ Gen. Superintendent” Subject Folders 5.72-73

“Steward’s Office Letterbook” Subject Folder 5.77

“Steward’s Office Meal Menus,” Subject Folder 5.78

“Steward’s Office Reports,” Subject File 5.79

SDC, 2006