Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Local Trustee

My DEAR DR. MACCRACKEN, Your letter of Feb 21st has finally found me down among the Florida Keys, and though I have had no official communication from the secretary of the Board of Trustees I am more than pleased with the action of the Board of Trustees at their last meeting. It is going to be a great pleasure for me to come into closer association with Vassar College and I am particularly looking forward, also, to seeing you more frequently and more intimately. Naturally, also, I am hopeful that I will be able to help in bringing the college into closer association with Dutchess County. Until you came to Vassar, we who had lived in the neighborhood for many years knew very little about the college or its work. In fact, for most of us Vassar might just as well have been a thousand miles away.

Franklin Roosevelt, February 1923

Thus began an association between the Roosevelts and the college that lasted until the death of Eleanor Roosevelt in November 1962. While Franklin was a trustee for many years, active or honorary, from 1923 until his death, Eleanor was a friend and frequent visitor. In the first years of the association, Franklin had more to do with the college than Eleanor; after a while, and especially after he became President, it was the other way around. Many times when Eleanor was in Hyde Park she would send down her car to the campus to pick up some Vassar students to come for a visit, or she might drive down herself, popping up on the campus-the invited guest for a meal of the students in the cooperative house–or for a lecture, or to give a talk at the Vassar Summer Institute of Euthenics in the summertime.

As Roosevelt’s gubernatorial and presidential jobs often caused him to be absent from Dutchess County, his visits to the college became less frequent, whereas Eleanor’s kept up steadily over the years of her life. Occasionally the MacCrackens were invited to an event at the summer White House on the river at Hyde Park. During the World Youth Congress held at Vassar in the summer of 1938, Eleanor Roosevelt’s presence at the conference, in which she was keenly interested, opened a new dimension in her relationship with Noble MacCracken. She came to his defense in the midst of many attacks from the right, which alleged that Vassar was making itself available to house the congress of an imputed communist group.

As America debated intervention on behalf of England and the Allies in 1940, however, MacCracken and Roosevelt approached a parting of the ways. MacCracken thought America’s entry into the war would resolve nothing, and he was opposed to Churchill’s position and the joint agreement of Roosevelt and Churchill adopted as the Atlantic Charter. On the Vassar campus, MacCracken had very few supporters among the faculty for his anti-involvement position, although among the students there were some who strongly agreed. As campus wartime tensions and anxieties increased in 1939, and until America’s entrance into the war in December 1941, MacCracken’s position, especially among his fellow administrators, became rather isolated with respect to the war issues. His colleague C. Mildred Thompson, the dean, was very much a supporter of Churchill’s position, and their relationship became noticeably strained when, in the spring of 1940, Thompson promoted a petition among the faculty urging the president of the United States to support England and the allies in their defense measures, short of war. When Roosevelt wrote a letter to Thompson thanking her for this effort, the silence towards MacCracken spoke for itself.

MacCracken was abroad on leave in Europe in the fall of 1922 when George Nettleton, the Yale English professor substituting for him as acting Vassar College president, went to Hyde Park and had, as he said, a “very pleasant talk” with Roosevelt, who had served as Woodrow Wilson’s Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Nettleton carried a message from the Vassar board of trustees, asking Roosevelt to join the board as a local trustee. Roosevelt’s only hesitation in accepting was whether he would be able to negotiate the board meetings with regularity because of his recently acquired polio, with which he was just learning how to deal. He agreed, nevertheless, to the proposal, and was elected to the board at the February 13, 1923, meeting. Roosevelt continued on the Vassar board through his New York gubernatorial tenure. In 1933, after he had become President, his ten-year trusteeship was due to end in June. The board desired him to stay on as honorary trustee while he was in the White House, however, and extended him the invitation to do so, which he accepted. He was still an honorary trustee when he died at Warm Springs in 1945.

The Roosevelts were from old, conservative, Dutch stock in the Hudson Valley, but their politics were more liberal than most of their fellow residents of Dutchess County, who by and large voted Republican. The future President did have a group of Democratic political associates in the neighborhood, such as Judge John Mack and other prominent local professionals, and later when he came back from Washington, he would count on these people, as well as his Washington aides, to help him negotiate his public appearances in Dutchess County. Speaking from the porch of the president’s house or the platform of the chapel, Roosevelt would sometimes use the Vassar campus as his stage.

Soon after FDR joined the board, MacCracken wrote him that he thought he would find the board of trustees “as active and as loyal as any board in the country.” This was a big change, MacCracken offered, from the situation eight years before when he himself came in as Vassar president. Then some members of the board still treated the college as “an expensive plaything,” he acknowledged. Now in the 1920s, MacCracken wrote, the trustees were a group of men and women characteristically eager to give time and thought to the development of the college. In June 1923 – a few months after Roosevelt came on the board-the trustees adopted the Vassar College Statute of Instruction, a new set of collegiate bylaws in which the college was conceived of as an organic institution and the duties and responsibilities of trustees, faculty, administration, and students were clearly set forth. Whereas under Taylor the trustees had engaged in many matters relating to the details of the academic side of the college, that was no longer the case by 1923. The Vassar Governance, as the new constitution was later called, soon became a model for government in academic institutions around the country, as well as defining MacCracken’s goals for autonomy at Vassar itself.

In MacCracken’s first years, the local trustees, who, in practical terms, tied and untied the purse strings of the college, lived in Poughkeepsie or nearby-John Adriance, Daniel Smiley, H.V. Pelton-and had a free reign in settling the day-to-day matters of the business part of the college. But after 1923, the local trustees ceased operating in that practical role. What MacCracken wanted for the college at that point was the election to the board of someone new whose presence could bring distinction and prominence to the connection. Roosevelt was the choice. Having Roosevelt on the board would draw the college into the affairs of the county, the state, and the nation.

It is not too surprising that MacCracken gravitated towards Roosevelt; they had much in common. They were both Democrats, they were both very community conscious, and each participated in many civic and political activities. Harvard-educated men, they were both quick-witted and had golden tongues. At a deeper level, they were interested in social change, yet steeped in tradition. When they made each other’s acquaintance, they must have seen how deeply they were both interested in the history of the county and their part of the country. Both of them early made the acquaintance of Helen Reynolds, a prominent local historian, who presided over the historical research of the Dutchess County Historical Society, of which they were simultaneously on the board. Both of them revelled also in digging up antiquities and connections with the earlier settlers of the past. Roosevelt was an inspired choice, all around, for local Vassar trustee, and in some respects, although not all, was MacCracken’s ideological matchmate.

The first assignment given Roosevelt as trustee was an appointment as chairman of a county committee (the other members of which were the warden, the dean, and the president of the Vassar Students’ Association), with the task of making plans for a Dutchess County Day at the college. This was a conscious step on the part of the college to become more visible and participatory in local Dutchess County affairs. Around the same time that Roosevelt was tapped as trustee in 1923, Laura Delano, his cousin, was invited to head a committee of local friends of the college “which,” MacCracken said, “we desire to form here in the county in order to promote more pleasant social relations and to let our neighbors know more about the work this really unique institution is doing. It seems a great pity that we should go on living together without knowing more about each other.”

“The index to Dr. Taylor’s Vassar did not contain the word ‘Poughkeepsie,’” MacCracken observed after retirement. “If I ever wrote a book about the college, it would be found.”

The local newspaper account of the event reported that over two hundred residents of the county visited the college on the first county day in 1924 at the invitation of MacCracken and the trustees. The guests were ushered first into the parlors of Main Building, where they were received by President MacCracken, Dean Thompson, Warden Jean Palmer, and four trustees: Mrs. Minnie Cumnock Blodgett, Mrs. M. J. Allen, Mr. R. G. Guernsey, and Mr. H. V. Pelton. Student guides, acting as hostesses, took the visitors around the campus and to the various halls. At four o’clock, a play, “The Garden of Wishes,” by Hallie Flanagan, soon-to-be Vassar’s theatre professor, later to be tapped by Roosevelt for the leadership of the Federal Theatre Program, was given by the students at the outdoor theatre, and after the play, the faculty met the guests at tea in the gallery of Taylor Hall, the elegant new art building, built in 1914.

Because the campus urgently needed a new dormitory to accommodate the mounting numbers of students, the Committee on Buildings, of which Roosevelt was at once made a member, was considering the erection of a new structure in the center of the quadrangle of dormitories and one classroom building, which would be linked to all the existing quadrangle dormitories and would provide a common kitchen for all – an earlier version of the All Campus Dining Center, ACDC, which in 1972 replaced Students Building, the early student center, built in 1913. One hundred and forty students lived off campus in 1923, and this plan would have improved dining facilities and freed rooms for dormitory space. The idea was scuttled when it was decided instead to develop Wing Farm, an area to the northeast end of the campus, and build Cushing House in 1928, along with Blodgett, Kendrick, and the Wimpfheimer Nursery School. During 1924 the Buildings committee voted “their moral obligation to erect Sanders Physics Building.”

Henry Sanders, chairman of the board earlier in the decade, had left money for that purpose, but the building had been much postponed when the Blodgetts loomed onto the scene with the promise of things to come in the way of an euthenics building. Roosevelt was very interested in these enterprises, and put forth his own ideas as plans were debated. When he couldn’t make meetings because of government commitments, he sometimes sent memoranda about his thoughts.

In 1925 trustee Roosevelt was especially concerned that with a rise in tuition the children of professionals-middle class people-would still be able to afford a college education. In his capacity as chair of the Committee on Religious Life, also, he presided over deliberations, which considered making attendance at Vassar chapel (non-denominational services) voluntary for the first time since the beginning of the college. The idea, promoted by MacCracken, was that the college president would invite the cooperation of faculty and students in planning for the “successful adoption, maintenance, and support of voluntary chapel service.” Roosevelt stated that he would hesitate to vote for the abolition of required chapel on Sundays and expressed the view that it would be well to separate the weekday and Sunday questions. The plan, which was finally adopted, catered to his ideas. The trustee minutes specified:

On such Monday evenings as the President may deem advisable, he may summon in assembly the whole of the college, not to last over one-half hour, at the same hour and in the same place. With the exception of a single hymn, such a meeting would not be religious but would be devoted to the consolidation of the ideals of the college. The remaining four days of the week would carry a simple religious service, not differing greatly from the then current service, as conducted by the president.

Those trustee deliberations preceded the acceptance of the idea of voluntary chapel services, and the institution of morning chapel talks given by MacCracken, a custom kept up for many years. (His notes for those talks, ranging in scope from recounting Chaucer’s tales to addressing contemporary social activism, constitute one whole box of documents in the MacCracken Papers in Special Collections.) Matthew Vassar had decreed that all sectarian influences should be carefully excluded from his college, but that the “training of …students should never be intrusted to the skeptical, the irreligious, or the immoral.” MacCracken’s presidential predecessors, all Baptist clergymen stretching back to 1861, had presided over required daily and Sunday chapel services, which some students and faculty, including the astronomer Maria Mitchell, had continuously fretted against even back in the early days. The clergymen presidents had also successively offered a mandatory and solemn presidential course in moral ethics for seniors, a kind of exit-into-life course, pulling together issues of morality. MacCracken was a man of deep religious convictions, but as soon as he became president, he requested from the trustees permission to abolish the ethics course and substitute instead a required course in the philosophy of the liberal arts education, to be offered to freshmen rather than seniors. Consistent with this resecularization of the Vassar educational environment, MacCracken was asked in 1929 to look into procuring a denominational pastor (chaplain) for affiliation With the college, to determine directions that might be followed in connection with campus religious life, but as there was no money in the budget for a new enterprise, he could not implement that idea at that time.

The general question, initiated by MacCracken, of Vassar’s helping William Lawrence to found the experimental junior college Sarah Lawrence came up in 1926, early in Roosevelt’s tenure. Certainly in 1926, it was helpful to MacCracken to have Roosevelt on the board as he heartily endorsed and supported the president’s forward-looking interest in the Sarah Lawrence collaboration. Later on in 1932, with Roosevelt still active on the board, the Vassar trustees declared themselves as more than pleased with the initial five-year development of Sarah Lawrence and asked MacCracken to continue his relationship as ex officio member of the Sarah Lawrence board.

In 1929 Roosevelt, by then governor of the state of New York, was a member of the first trustee committee on undergraduate life that, among other questions, established permission for students to smoke in particular places on campus. (Later in November it was proposed by the newly formed household management committee of the trustees that the rooms thus set aside for smoking, should be known as “rooms in which students may smoke,” not as “smoking rooms.” That way, it would be clear that the rooms could be kept under the supervision of the wardens, and that smoking could be controlled.) The governor was also a member of the first trustee endowment committee, which established the need for an assistant to the president to work on money-raising, a move which in turn led to a separate development office in 1929.

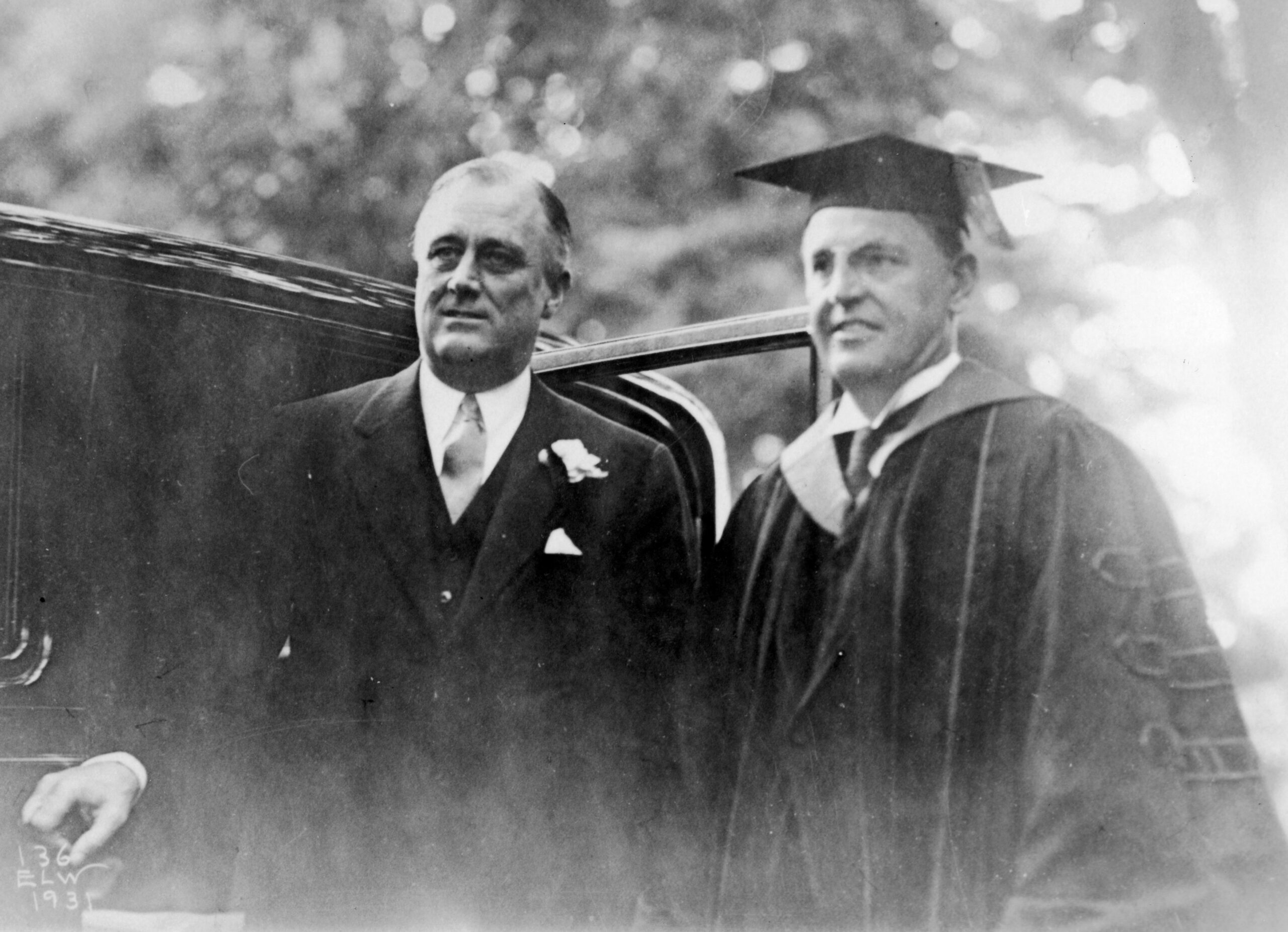

On the tenth of June 1931, Roosevelt, then in his second term as governor, delivered the Vassar commencement address. Ahead of time Roosevelt thought it was likely that he might have to miss the commencement, so Stephen Duggan, fellow trustee and head of the Institute of International Education, the I.I.E., agreed to stand in if necessary, in which case he would have given a specially prepared address on “America’s Place in International Affairs,” an appropriate topic for one who had done so much to promote international education at Vassar and elsewhere. But Roosevelt did turn up, the first governor of a state to deliver a commencement address at Vassar, and gave a short speech on the theme that study is like navigation, liberally illustrated with anecdotes to bring home his point. The speech conveyed the idea that “the crass ignorance of the educated classes about governmental matters [was] one of the most appalling things about the post-war years” and the students were exhorted to do better than the older generation had done to understand what was going on in governmental affairs around them.

Two years later on June 1, 1933, MacCracken proudly reported to the trustees:

For the first time in the history of Vassar a trustee of the Board has been elected to the highest office in the country. Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose term expires with this meeting, has maintained throughout his connection with the college undiminished interest in its work. While his administrative duties have prevented his attendance at recent meetings, he has been most faithful in personal conferences and in correspondence. The many contacts which the college enjoys both with the President and Mrs. Roosevelt must remain a treasured part of its history. MacCracken had determined a course of action to keep Roosevelt interested in remaining on the board as an honorary member, however, knowing that his affiliation would continue to lend distinction to the college even if the President didn’t have time to do his trustee homework. Thus before Roosevelt’s trustee term was up, in April of 1933, MacCracken sent a short but pithy progress report to the White House about how the town-gown projects were going: the students were making surveys for various local agencies and the college was opening its doors more widely to townspeople for concerts, lectures, and forums. Roosevelt was invited to attend commencement, to make his final appearance as active trustee, an invitation which he had to decline. At a board meeting near the time of commencement, however, the trustees unanimously voted to ask him to stay on as honorary trustee, which Roosevelt agreed to do. MacCracken put it this way in his letter of invitation: “Your post was described as carrying with it all the authority you would like to exercise, and none of the responsibility.”

After Roosevelt had agreed to stay on the Vassar board, the MacCrackens gave an August reception for him, to which residents of the county were invited. MacCracken went to Hyde Park to escort Roosevelt to the campus, and joined Roosevelt in his open and specially-equipped car for the ride back. During the ride, Roosevelt gave him a lesson in how to pose for photographs, first greeting people standing on one side of the road as the car went through, and then on the other. Roosevelt said to MacCracken, “You’ll learn,” the Poughkeepsie Evening News dutifully reported on August 26, 1933. MacCracken and Roosevelt were having a wonderful time, each associating with the other, fellow masters of histrionics.

Roosevelt delivered his speech from the MacCracken’s front porch, after an introductory greeting by MacCracken who said:

Mr. President: The people of Dutchess County bid you welcome. You have graciously fulfilled your promise in coming from your vacation days, days that for anyone else would be called hard work, to speak again to your neighbors. A year ago when you spoke to us at Washington Hollow [nearby township], there were whispers in the air, whispers about somebody that was a stranger to us of Dutchess County. He was whispered to be vague. He was thought to be timid. He was rumored to be weak. Worst of all, we heard he was aristocratic. We had never known such a man, and we wondered whom they had considered. Now the rumors and whispers have died away, and a great chorus of praise and pride has filled our ears. A man stands out whom everybody knows. The portrait is more familiar but not even his neighbors knew him last year as the world knows him now. He has taught us to be strong. He has kindled his courage in our own hearts. He has drawn for us a clear and definite plan by which through sacrifice and cooperation, American democracy may survive. And best of all, he has placed human values first, and has affirmed that the state exists for the welfare of all, and not least for the common men and women like his neighbors.

During these Depression years, MacCracken advised Roosevelt from time to time what people in the Vassar community were thinking; he believed that the college might represent a kind of listening post. One sign of recovery from the Depression, for example, he pointed out to Roosevelt by letter in 1934: advance registration for future classes at Vassar from January to July in 1934 was the largest in over ten years, and in 1934 fewer students needed special aid. (The college during the Depression had gone on to a semi-selfhelp regimen, designed to cut down on college and student expenditures. Some students maintained their own quarters and did their own housekeeping, and a cooperative house was established, at first in euthenics quarters in Blodgett Hall, in which students also did their own purchasing and cooking.) In 1935 when Harry Hopkins, the old childhood and Grinnell College friend of Hallie Flanagan, drew Roosevelt’s attention to her as a promising candidate for the directorship of the Federal Theatre program (part of the Federal Emergency Relief program), MacCracken lost, at least temporarily, an outstandingly innovative faculty member and one who had already brought great liveliness to the Vassar community as director of the Vassar Experimental Theatre. By that time the Vassar theatre had come into national prominence. Eleanor Roosevelt had attended some of Hallie’s lively interdisciplinary Living Newspaper plays, which explored serious contemporary issues and experienced their excitement. When Hallie travelled to Washington at Hopkins’s invitation to consider heading the program, Eleanor supported her for the position.

When Roosevelt was reelected in 1936, MacCracken sent him a telegram saying: “Our cup runneth over,” to which Roosevelt replied: “Dear Henry: That is a mighty sweet note of yours.”

Yet, as indicated above, everything was not entirely harmonious between MacCracken and FDR, as World War II approached. In May 1940 seventy-five Vassar College students signed a letter to FDR protesting that they did not agree with him on the war-peace question with regard to the United States’ role in the European conflict. MacCracken’s own stand on American involvement in World War II was in direct conflict with FDR’s foreign policy-which he often explicitly criticized. Although in February 1941, and again in April of the same year, he declined to join the America First organization (with which he was flirting because its philosophy of non-intervention approached his own), MacCracken gave several speeches and made many public statements that year in keeping with his pacifism, endorsing a noninterventionist policy.

In August 1941 MacCracken gave such a speech at Carnegie Hall, after which FDR made it immediately clear that he disapproved strongly of American isolationists, pacifists, and non-interventionists. After FDR announced in September 1941 that United States ships would fire upon threatening Axis ships, MacCracken appeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to testify against the proposed changes to the 1939 Neutrality Act, which would allow American ships to be armed. Pearl Harbor sharply ended MacCracken’s involvement in the anti-war movement, but Roosevelt and MacCracken did not thereafter resume their former cordial relationship.

Dean C. Mildred Thompson, on the other hand, was very openly in favor of Roosevelt’s policies during the same period. The two administrators had to agree to disagree over this issue, which provoked some strain between them. When one hundred and twenty-five faculty members wrote a letter to Roosevelt in October 1941 pledging their support of his foreign policy, Mildred Thompson sought to soothe MacCracken’ 5 anguish by sending a formal note to her colleague, of whom she was genuinely fond, in advance:

My dear President MacCracken, With a sense of courtesy and respect for you, and in understanding of your genuine belief in the right of free expression, both within the college and without, we wish you to have a copy of our statement of public policy before it goes to the President of the United States, and before it may appear in the press. We feel sure you will receive this statement in the spirit of tolerance for different opinions which you have long shown and which we greatly value. … — Mildred Thompson

Roosevelt’s easy interaction on many occasions with individuals and groups of people in MacCracken’s and Thompson’s Vassar, especially in the thirties and forties, awakened many students, and even faculty members, trustees and parents, to politics and national affairs, to taking sides and thinking for themselves on issues of war and peace, and the unsolved Depression problems of hunger, homelessness, and unemployment.

MacCracken’s arm, reaching out into the community to bring outsiders in, and his knack for encouraging students both inside and outside classrooms, to become engaged with the developments of their own times, were nowhere more observable than in the college’s give-and-take relationship with the Roosevelts. For some students, indeed, the opportunity to meet or just hear from a local platform, Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, and discover how they thought, presented themselves, listened and got things done, constituted the essence of experiential learning, which was the fulcrum of MacCracken’s theory of education. For at least one student, who grew up during the Depression years, subjected to conservative parental fulminations against the “country squire in the White House,” the chance to get an entirely different slant on the Roosevelts, showing their sides as concerned educators, county citizens and neighbors, proved MacCracken’s point.

Note: This essay is adapted from “Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Presidential Neighbors” in Elizabeth A. Daniels, Bridges to the World, Henry Noble MacCracken and Vassar College, College Avenue Press, Clinton Corners, N.Y., 1994

Sources: Henry Noble MacCracken Papers, Vassar College Archives, Boxes 2, 72, 120, The Vassar Trustee Minutes, passim, Vassar College Archives, The President’s Personal Files, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York (Public Access).

EAD, 94