A History of Coeducation

Since the late nineteenth century, Vassar had seldom suffered financially or experienced any problems concerning the qualifications of its applicants. By the late 1950’s, however, the college’s single-sex environment became increasingly unattractive to active and socially conscious young women. Due to many factors, including the 1950’s mainstream media’s emphasis on the importance of marrying early, women entered college with the expectation of finding their future husbands and starting a family. In addition, a greater number of incoming Vassar students were arriving from public, coeducational schools rather than private, single-sex ones. Coeducation was becoming the scholastic norm, and attending a women’s college seemed decidedly retrogressive to many applicants.

By 1961, the Vassar administration understood that change was imminent. President Sarah Blanding predicted, “Of the hundred or more women’s colleges now in existence, no more than ten will be functioning in the year 2061.” In response to the evolving problem, the faculty voted in 1962 to investigate different methods of incorporating men more fully into Vassar life—whether by opening a coeducational graduate facility, or by accepting men as members of Vassar’s undergraduate student body. Vassar had educated men in a unique and short-lived program after World War II, but no such experiment with coeducation had been attempted since.

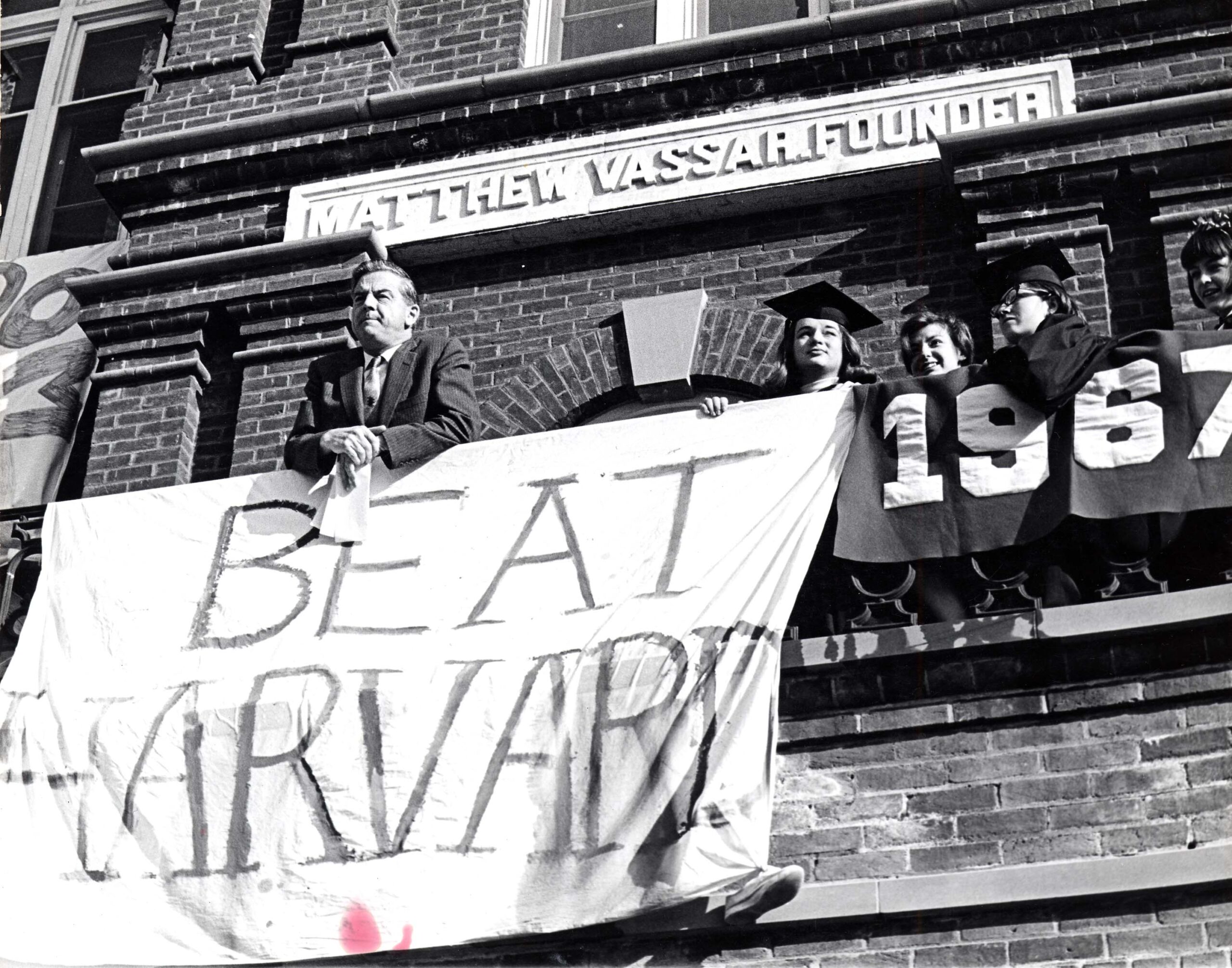

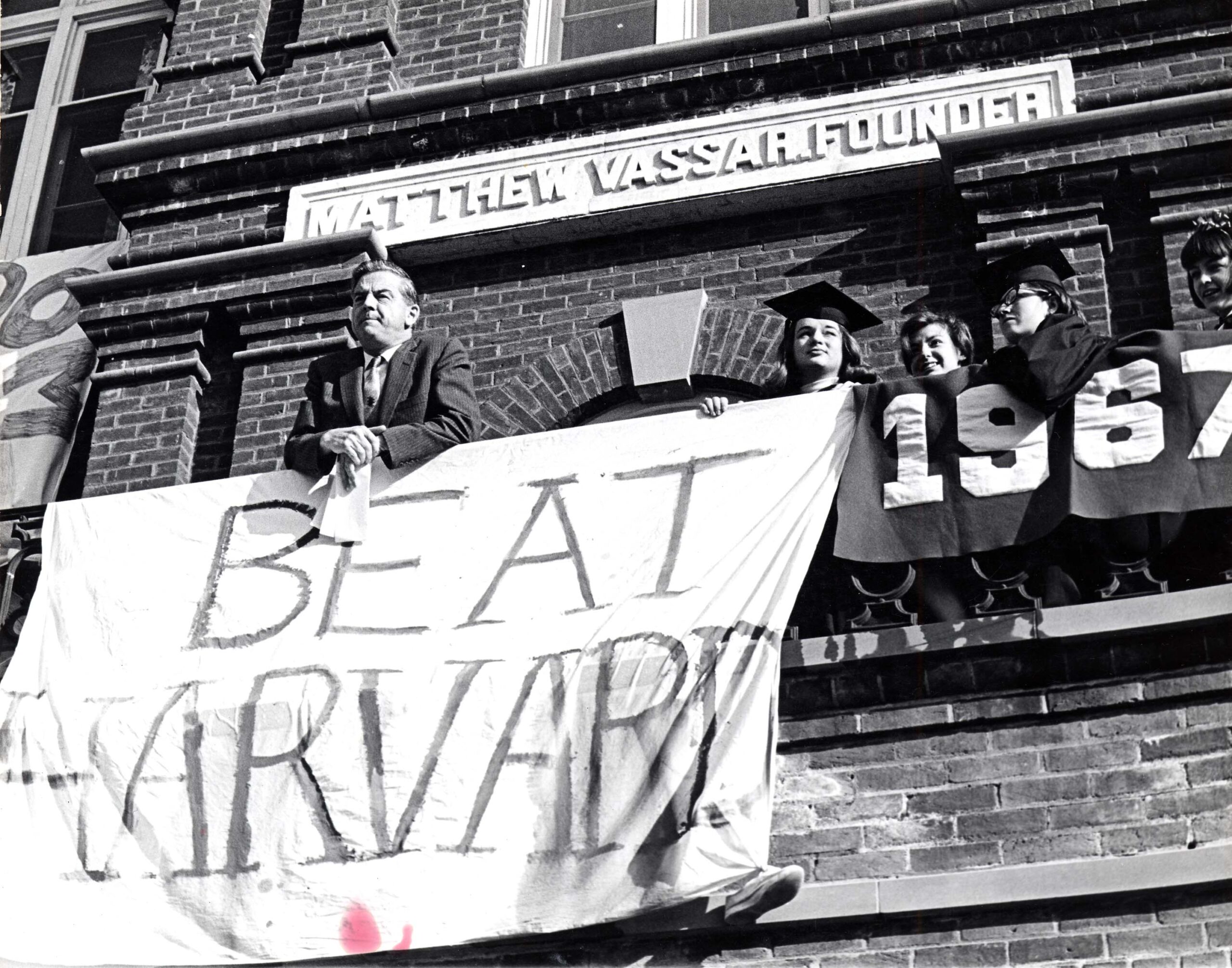

The 1966 decision to create the Committee on New Dimensions therefore proved monumental for Vassar. This president-appointed committee hoped to respond to increasing student demand for greater curricular flexibility, independent study, and reconsideration of certain social regulations. Most of all, the committee felt a need to reply to the student’s divided school-week: each weekend saw a mass exodus from Vassar to various coeducational or all-male campuses, to attend dates or mixers.

In November 1966, when President Alan Simpson accepted an invitation from Yale University president Kingman Brewster to consider Vassar’s relocation to New Haven, one possible solution arose—Vassar girls might make their “weekend exodus” permanent. Simpson agreed to examine the prospect of joining forces with Yale, if only to create a forum in which to discuss potential change within the Vassar community. The movement soon met with considerable resistance from Vassar alumnae who insisted on a counter-study, which would examine the effects of Vassar remaining in Poughkeepsie.

Under Dean Elizabeth Daniels, this new Committee on Alternatives reconsidered building a graduate center, pursuing coeducation, and refocusing the current curriculum. The results of a questionnaire circulated by the committee proved especially telling: the majority of students polled believed that “the absence of men in Vassar classes involve[d]… an important loss of perspective.” A vast majority of students also expressed the desire to attend either a coeducational college or a women’s college closely affiliated with a major university like Yale. The students had spoken, and either a move to New Haven or the introduction of coeducation at Vassar seemed imperative. The question at hand became one of “how best to preserve Vassar’s identity, its highly selective student body, and its traditional mission of improving opportunities for women,” while meeting the students’ demands. A move to New Haven would inevitably threaten Vassar’s identity; the college’s rich and unique history would, perhaps, fade slowly into the fabric of Yale’s epic arras. For this reason, and because they feared being demoted to “second-class status in Haven,” Vassar faculty strongly opposed relocation.

Attempts to implement a coeducational graduate institute at Vassar failed almost immediately. A number of alumnae, trustees, and senior faculty members favored the invention of consortium similar to the Claremont Colleges; Vassar would persuade certain all-male colleges to relocate to Poughkeepsie and become coordinate colleges to Vassar. But in May 1968, faculty overwhelming endorsed—102 Ayes to 3 Nays—the admission of men to Vassar itself. The reason for this outcome, as stated in A Report on the Education of Men at Vassar (1968), possibly stemmed from the faculty’s fear that only the Board of Trustees would shape the new coordinate colleges. By introducing coeducation at Vassar itself, the entire college population would be involved in its implementation, rather than just a select group.

By the summer of 1968, Dean of Faculty Nell Eurich had laid plans for a more academically flexible Vassar. A new Vassar necessitated a more progressive scholastic program. With her reconstituted Committee on New Dimensions, Eurich encouraged “constant adjustment” to Vassar’s curriculum, “with an increased number of options for both students and faculty.”

In October 1968, Vassar began negotiating with Bowdoin, Amherst, Dartmouth, Williams, Colgate, and Trinity, in hopes that the institutions might form an exchange program for male students interested in entering Vassar for the second semester of the 1968-69 academic year. Soon, a twelve-college exchange was formed, and seventy-seven male students entered Vassar that spring semester. Over one-third of these men applied to transfer to Vassar at the end of the semester, and by March 1969, Vassar had amended its constitution to include the education of men.

The following fall, Vassar would admit both male exchange and male transfer students, and would allow already matriculated students to take leaves to pursue the remainder of their undergraduate career elsewhere – if they saw fit to do so (before that point, the administration did not allow Vassar students to transfer once enrolled).

As one can imagine, the introduction of men into the Vassar environment made explicit the need for certain changes and improvements on campus. Due to a considerable increase in population size, the college built the Terrace Apartments and Town Houses to alleviate the housing crunch. A new dining center with longer hours of operation replaced in-dormitory dining. And, to the shock of many, President Simpson revoked parietal regulations on campus. The Vassar admissions team also saw a sharp break from tradition: by 1968, Vassar recruiters no longer made its decisions “in tandem” with the other Seven Sisters colleges. Instead, they hired new staff, and increased their annual high school visitations over 1000%. Vassar recruiters clearly felt the need to inform high school guidance counselors of the college’s shift to coeducation.

Another change concerned Vassar’s population increase. The college initially intended to increase its student population from 1,550 to 2,400 and to aim for parity between the sexes. While the college revoked its initial goal of parity in 1971 – pleased with the then-current figures of 2,250 students and 40% men – the idea of intellectual, if not statistical, parity remained. In June 1973, alumna chair of the Vassar Board Elizabeth Purcell ’31, raised the increasingly pertinent question, “Isn’t a famous woman’s college denying its historic mission [in becoming coeducational]?” Purcell answered “No,” and insisted that Vassar was developing an equal coeducation, in which women would not be marginalized or discriminated against. “Vassar’s commitment in this second century,” she said, “is every bit as new and exciting as it was in its original commitment in 1861.” Most important in the administering of coeducation, then, was the ensuring of relative equality between genders, in order to promote a non-sexist atmosphere. In fact, one male alumnus remembers learning foremost how “to be subordinate to women” at Vassar. While pursuing leadership roles in student government or with The Miscellany News, he became accustomed to having a woman superior.

Athletics became another integral ingredient in the development of Vassar’s unique coeducational atmosphere. Before the college’s founding in 1865, Matthew Vassar had stressed the importance of athletics on campus. Dismissing then-contemporary ideas that excessive physical activity detracted from a woman’s reproductive abilities, Vassar called for mandatory light gymnastics as part of the college curriculum. With the advent of coeducation, however, the athletic department was in desperate need of new coaches and improved sports fields. In 1978, sports facilities were still inadequate. But by 1980, the college had organized varsity teams for both sexes. Importantly, men’s and women’s teams received equal funding. And over the next few decades, Vassar developed eighteen varsity teams, nine for men and nine for women. (In 2006, Vassar students have their choice of twenty-three intercollegiate sports.)

Perhaps the athletic slump between 1967 and 1978 stemmed in part from a general uncertainty as to just how masculine the new Vassar males would be. The question became, “what kind of men will Vassar attract?” One Esquire article centered on the especially flamboyant “Jackie St. James” (Jack Sheldon Weiss ’74), and portrayed Vassar males as characteristically gay or effeminate. And while Vassar now boasts a considerably gay-friendly atmosphere, an alum from the class of ’78 recalls knowing only a few openly gay students and no openly gay professors during his time at Vassar. Similarly, a gay alum remembers Vassar being a rather “benign” environment for gay males; students were “generally accepting as long as gays did not become too visible or too confrontational.” And this non-confrontational atmosphere seemed to define the Vassar male population of the day. Sexuality, for the most part, was not a topic of conversation. Few straight men felt it necessary to boast about how often they were “bedding women”: “you scored, you didn’t score: no one cared.” Individuals felt generally free to develop their own personalities, but privately.

In focusing on Jackie St. James, then, Esquire also seemed to misrepresent how diverse the original Vassar males truly were. One ’74 alum would later became a policeman, and would put forth the idea of men pairing up with women to walk the streets, rather than the traditional men-men teams. By doing so, he brought a greater number of women onto the streets, and disproved the notion that women could not hold their own outside the police station. “I am certain,” he said, “but for my Vassar background, I wouldn’t have pushed the issue.” Richard Roberts, a ’74 grad and one of Vassar’s first black male students, found himself forced into the role of revolutionary while at Vassar. Roberts, who became a U. S. District Court Judge, recalls an English professor revising her syllabus to include African-American literature, shortly after he joined her class. Not knowing which novel to study, however, the professor asked Roberts for his opinion, and then invited him to lead the class in discussion. A student named Ed, on the other hand, was considered an “oddity” for his interest in athletics. He gained a reputation as a reclusive weight lifter, and could usually be found in the dorm basement, alone with his barbells.

While the early Vassar men had inevitably varied experiences, most seem to agree on the presiding feeling of loneliness during the first year or so. While being surrounded by women seemed a welcome prospect, many men found themselves craving “buddy” time. Over the next few years, the sex ratio would even out, and male students would learn to build strong relationships with their female peers. Living at Vassar not only became more comfortable, then, but Vassar males began to pride themselves in being “brothers in a special sisterhood.” As one alum puts it, “no one but those noisy admissions folks obsessed about [sex ratios] on a daily basis… What we did obsess about was the notion that, as a group, we were unique.” Evidently, the new Vassar was proving markedly different, even from other coeducational colleges. Accordingly, the Vassar male became a “type” unto himself – socially aware, sensitive, and humble. Just as opening a women’s college had been considered revolutionary in 1865, making the same college coeducational, and also retaining its decidedly non-sexist atmosphere, would prove equally revolutionary in 1969. And while modern-day Vassar proves to be dramatically different from the Vassar of 1970’s, a certain unique spirit still pervades on campus. The Vassar sex ratio hovers around 60% women and 40% men, but one hardly feels any gender imbalance. If anything, one notices the subtle effects of that golden ratio—the familial campus vibe, the resounding sense of sensitivity among both male and female students. And perhaps this is what Esquire misinterpreted back in the 1970’s: Vassar men—regardless of sexuality—can wear pink unafraid; our women, similarly, act and dress however they see fit. Coeducation at Vassar is best shown not through statistics or stereotypes, but through our students’ fearless assertions of their individuality, despite the perceived limitations of the male and female genders.

Related Articles

- Curriculum

- Forrest Cousens: A Short History of the Vassar Veterans and Some Memories

- The Vassar-Yale Study

External Links

Trustee Barbara Austin Foote ’40 presented her reflections on the Vassar coeducation decision in a paper she delivered to the Chicago Fortnightly Club in 1973. Her daughter, Markell Foote Kaiser ’66, included excerpts from her mother’s paper in an essay in The Vassar Quarterly in 2004.

Sources

Elizabeth A. Daniels and Clyde Griffen. Full Steam Ahead in Poughkeepsie. Vassar College, 2000.

Sebastian Langdell’s 2005 Interview with Elizabeth Daniels.

SL, 2005