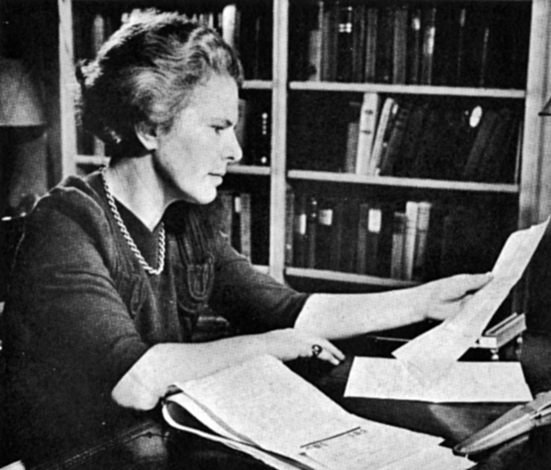

Virginia Kirkus ’1916

In 1967, as chairman of their 50th reunion, Virginia Kirkus Glick ‘16 wrote a characteristically vigorous invitation to her class, echoing Lewis Carroll in a playful poem:

“The time has come,’ the Walrus said,

To talk of many things:

Of shoes — and ships — and sealing-wax —

Of cabbages — and kings —

Of what VC has meant to us

Through all these fifty years.

Of how its helped to mellow us

And temper all our fears.

Please plan to come on June the tenth

And chew the fat with the others,

Lest life in our advancing years

Be just a case of druthers. . . .

Whether you come to lend an ear,

To argue or expound

Remember what we really want

Is your bonny face around.”

She continued, encouraging her classmates:

“we graduated into the First World War: we acquired a boom and a depression; we experienced some brush fire wars —and then a Second World War; and throughout social changes that have altered the lives of everyone. That ought to add up to something special and surely we have not insulated ourselves. It has done something to us. So let’s talk it over, take our hair down, and exchange ideas and opinions. Come back and see the changes that IBM has wrought. Remember Raymond Avenue and its lovely trees, the quiet rural setting? Come back. It is different and we suppose we are, too.”

Born on December 7, 1893, in Meadville, Pennsylvania, Virginia Kirkus was the daughter of Reverend Frederick Maurice Kirkus, an Episcopal minister, and Isabella Clark Kirkus. The eldest of five children—Harriet, born in 1894; Alice, born in 1895; Maurice, born in 1897; and Mildred, born in 1904—she spent most of her childhood in Wilmington, Delaware. At the age of eight, she told her father that when she grew up she wanted to “make books.” Her education began at Misses Hebb’s School in Wilmington, after which she attended Hannah More Academy in Reisterstown, Maryland.

Virginia entered Vassar College in 1912, beginning a very active life on campus. She held several class offices including class president and Council representative and was in the Daisy Chain. Graduating in 1916 as an English Major, she stayed connected to Vassar, serving as chairman on the 25th, 50th, and 60th reunions and as class representative on the alumnae council. She served on the board of the New York Vassar Club, was a member of the Fairfield County (CT) Vassar Club, and maintained a lifelong friendship with several of her Vassar graduate friends.

In a 1977 biographical alumnae update, Virginia lamented that none of her relatives had been able to attend Vassar because “our younger relatives cannot afford it now…much to my regret,” and, in her 87th year, she attended a spring alumnae brunch in 1980.

After graduating in 1916, Virginia Kirkus attended Columbia University Teachers College and received her teacher’s certification from Tower Hill School in Wilmington, Delaware, where she subsequently taught history and English at the Greenhill School. In 1920 she moved to New York City to work as assistant fashion editor for the popular fashion magazine, Pictorial Review. Later, serving simultaneously as an editorial associate at McCall’s and as a freelance writer at Doubleday, she also wrote what she described as “the skeleton in the cupboard book,” Everywoman’s Guide to Health and Beauty (1922). Looking back, in 1964, she redeemed the book, recalling that it “sold 50,000 copies which is not to be sneezed at even in those days.” At McCalls, she handled columns on beauty, home decorating, child care, and etiquette, and responded to letters from subscribers. She described this time as “a good experience, but I was glad to escape what seemed to me the shifting sands of magazine editing to the greater permanence of books.”

Ms. Kirkus settled in 1925 in Redding Ridge, Connecticut, and the desire to work with books led to a job editing juvenile books at Harper & Brothers. She recalled this work as “trail blazing… we were ‘first’ in the area of importing in translation picture books from foreign countries. We were ‘first’ in doing fact books for youngsters of inquiring minds—and this was an uphill proposition. We were ‘first’ in feeling that toy books could have literary value, again we bucked an adverse tide.” Her hard work and passion for books paid off; in 1926 she became head of the children’s book department at Harper, where she remained until she started her own business in 1933. During her time in Connecticut, she served for twelve years on the board of the Mark Twain Library, founded in 1906 by Samuel Clemens, and on its building committee.

Weakened by the Depression and forced to close the children’s department, Harper offered Virginia another job. Instead, the next year she moved to Greenwich Village and, with ten subscribers, launched from her home her own business, the Kirkus Bookshop Service. The idea for this innovation had come to her while she was returning from an eight-week visit to her father, who was serving as the rector of the American Church in Munich.

Claiborne Smith, editor in chief in 2013 of Kirkus Reviews, saw Virginia’s next move as a reflection of her “eye for dramatic publicity. Rather than wait until she returned home to New York to mail the 25 letters seeking the opinions of important booksellers and publishers, she decided to bring a little flair to the endeavor: When the ship was still 24 hours away from the New York harbor, she paid to have a small plane airlift the letters. Virginia Kirkus, who was 38 at the time, was never faulted for a lack of conviction in her own ideas.”

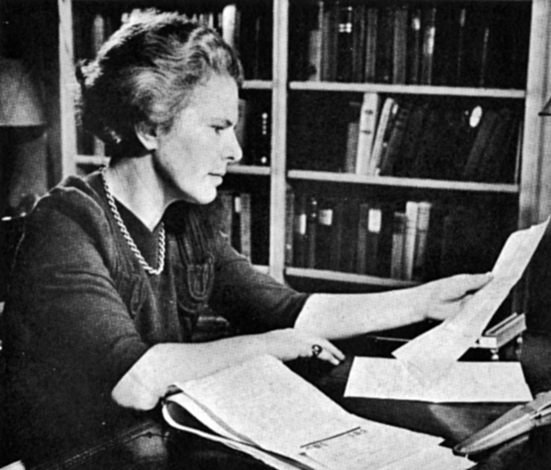

Virginia’s invention screened soon-to-be-published books, thus helping booksellers determine which books would interest which customers and which wouldn’t. Her idea, as she described it, was to provide booksellers “with brief, informal and impartial reports on books, based on actual reading, several weeks in advance of publication.” To provide this service, Kirkus soon found herself reading and reviewing an average of over 700 books a year.

However, Kirkus’s goal—objectively describing the appeal and predicting the popularity of new publications—was, Claiborne Smith observes, from the beginning “a high-wire act of diplomacy. To create the Service, publishers needed to trust Kirkus with their galleys (which she had to return after reading), but bookstores and librarians expected the unvarnished truth about a book’s quality and its potential to sell. There were bound to be dust-ups. In 1935, despite all of her careful negotiations with publishers, a letter Kirkus wrote led to 10 publishers wanting the Service to end.” The dissenting publishers saw in Kirkus’s letter an implication that their salesmen did not themselves read the books they were seeking to sell. Her reaction was to hold individual conferences with these publishers, all but one of whom maintained subscriptions to the Service. “The one ‘rebellion,’ as she put it, was a publisher named Appleton-Century. ‘I’d feel differently about it if you were a man,’ their president told her as a parting shot. ‘That’s something else about which I can do nothing!’ she retorted.

In later years, Kirkus herself admitted that Kirkus Reviews, although generally highly accurate, made mistakes: she advised her clients that Hervey Allen’s Anthony Adverse (1933) would be too long to attract readers and she had dismissed Thomas Wolfe’s Of Time and the River (1935) as having only “snob appeal.” Some of the bestsellers she recommended were Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (1948), Mister Roberts, by Thomas Heggen (1946), Cheaper by the Dozen, by Frank Butler Gilbreth and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey (1946) and Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny (1951). Overall Kirkus’s percentage of guessing right about a book was 85 times out of 100. In her success, she kept in touch with Redding and gave many of her review copies to the Mark Twain Library. She also returned there to give an annual lecture, “What You Will Be Reading This Winter.” The library’s staff called Ms. Kirkus “The Library Builder.”

Three years after starting her business, on a ship traveling to Mexico, Ms.Kirkus met her future husband. The executive director of placement and personnel for the Associated Merchandising Company in New York City, Frank Glick had graduated from Princeton, where he was the captain of the varsity football team in 1915. They married on June 5, 1936, in New York City, the new Mrs.Glick wearing an aquamarine gown and corsage of white orchids and lilies of the valley.

After their marriage, Frank and Virginia bought an old house in Redding Ridge that had no heating or lighting and only a hand pump for water. The renovated house, which they named Windfall, served as their weekend getaway from New York City for the next thirty years and also as the inspiration for A House for the Week Ends (1940)—by Virginia Kirkus— which the renowned “Bookman” of the San Francisco Chronicle, Joseph Henry Jackson, greeted with kudos: “For once here is a house-in-the-country book that is neither cutie-pie nor ecstatically mystical. Instead, it’s a ‘how to’ book of rare quality.” The Glicks’ love of gardening and Virginia’s lifelong dedication to the Rock Garden Society led to Virginia’s First Book of Gardening, published in 1956 and revised in 1976.

In 1962 Mrs. Glick incorporated Kirkus Reviews, and, reluctant to “step out of the picture,” she remained president of Virginia Kirkus Service, Inc. She retired, however, in 1964, at the age of 71. Virginia and Frank then set off on new adventures. In the spirit of their first meeting, they set off to travel the world in 1963-64. Retiring to Windfall in 1966, they planned further ventures. In 1969, they made an extensive trip through South America, and later visited Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Mexico, Russia, the Canary Islands, Spain and Africa, which they visited four times.

Their trip to Russia in 1979 was their last. Frank died suddenly thereafter, and Virginia wrote fondly of this last time together, saying it was “a fabulous trip that we’d have not missed. For August brought the sorrow of Frank’s sudden death. The one thing I cling to is the richness of my memories of 43 wonderful years with an ideal companion. Many of you will remember the zest with which we shared our reunions—the friendships he made—the sensitive response to human needs. We both recognized how lucky we were.” Virginia continued her travels alone, travelling to China at the age of 84. Virginia Kirkus Glick died at the age of 86 in Danbury, Connecticut, on September 8, 1980.

In 1964, the first alumna in its 132-year history to be asked back to Hannah More Academy to give the commencement address, Virginia Kirkus Glick shared a personal reflection in her address, “On Facing my Fiftieth.” “It must be somebody else,” she said, “Surely not ME. But there it is—Graduated HMA 1912. Vassar 1916. Where have the years gone? What have I to show for them? What of the years ahead? (Yes I’m making plans for those years ahead— incredible as that may seem to the graduated at HMA in 1962… but the queer part of it all is that I don’t feel old— fifty years later. I still have two prime ingredients: —health and happiness. I still have as much— sometimes more of the work I love. I still enjoy my two homes, winter (and mid-week) in New York City; the summer (and weekends) in Connecticut. I like housekeeping—and I’m a good cook, if I have to point to my husband, Frank Glick, to prove it. . . . I like gardening . . . . I Like traveling and theatre and music and books. Oh yes, after thirty years concentration on books, I still love to read.”

Kirkus Reviews continues to review over 7,000 publications each year.

SOURCES

“Virginia Kirkus.” Current Biography, June 1954.

Virginia Kirkus Glick, “How to Read Five Thousand Books,” Vassar Quarterly, vol. xxvi, no. 3, January 1, 1941.

“College Club to Elect Officer at Yearly Dinner: Virginia Kirkus to be Guest Speaker Thursday.” Reading Eagle, May 7, 1948.

“Her Memory Foiled a Prison Plagiarist,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, March 18, 1953.

“Virginia Kirkus, Started Reviews of New Books to Help Stores, 86” New York Times. September 11, 1980.

“Class of 1916 Reunion Invitation,” Vassar College Special Collections (VCSC), AAVC Box 45. September 9, 1965.

Kirkus, Virginia, “On Facing my Fiftieth.” VCSC, AAVC Box 45. 1962.

Smith, Claiborne, “Our History,” https://www.kirkusreviews.com/about/history/

HK, CJ 2018